No. 435: April Employment/Unemployment, Money Supply and Velocity, Systemic Stress,

COMMENTARY NUMBER 435

April Employment/Unemployment, Money Supply and Velocity, Systemic Stress,

March Construction Spending

May 4, 2012

__________

For Second Month, Household-Survey Employment Fell as Payroll Growth Faltered

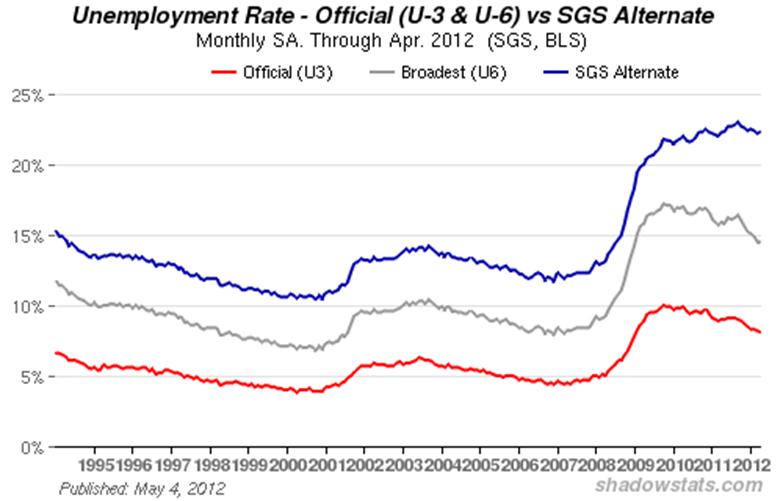

April Unemployment: 8.1% (U.3), 14.5% (U.6), 22.3% (SGS)

Annual M3 Growth Weakened in April as Velocity Rose

New Indicator Shows Intensifying Systemic Stress

Impaired Construction Spending Continued

__________

PLEASE NOTE: The next regular Commentary is scheduled for Friday, May 11th, and will cover the April PPI and March trade balance data. The Public Comment on Inflation Measurement will be published on Monday, May 7th.

Best wishes to all — John Williams

Opening Comments and Executive Summary. A renewed faltering of U.S. economic activity is a fortuitous development for the bank-propping needs of the Federal Reserve. As suggested by the systemic-stress indicator discussed in the Hyperinflation Watch, the banking systemic remains severely stressed, with some form of new easing—a QE-3—likely just a matter of time, and likely sooner rather than later. All Fed actions since the crisis of 2007 and panic of 2008 have been aimed at saving the banking system—not the economy—where the survival and health of banking system is the Fed’s primary function. The federally mandated niceties of maintaining sustainable economic growth and containing inflation are secondary concerns for Mr. Bernanke; there is little the Fed can do to stimulate the economy or to contain inflation.

In the current political environment, however, the Fed likely would run into heavy public opposition to an ongoing effort to bailout the banking system. Accordingly—as has been the general circumstance—any new form of easing will be justified under the cover of an effort to boost economic activity.

Employment and Unemployment. The labor situation suddenly has started to weaken expectations of U.S. economic growth. While some of the softness in the latest data is due to catch-up from earlier overstatement of economic activity, there is a much-weaker, underlying economic reality in play that still has not worked its way into official reporting or into market expectations.

Softening Payroll Data. The April payroll-survey employment gain of 115,000 was below already-weak consensus expectations, for a second month (although the headline March gain of 120,000 revised to 154,000), while the household survey showed an outright monthly employment contraction for the second month. None of the month-to-month changes were statistically significant, as usual, but year-to-year change in nonfarm payrolls has begun to slow markedly.

The preceding graph shows updated levels of nonfarm payrolls. The current level remains well below the pre-2007 recession peak. This coincident indicator of economic activity shows no recovery in place.

Updated Trend Numbers. As discussed in Unpublished Payroll Data (announced in Commentary No. 434), the trend estimates that are generated by the BLS’s monthly seasonal-adjustment process indicate where upcoming month-to-month changes in payroll data would come in, based on a simple trend model and fully balanced seasonal factors. As a result of today’s (May 4th) reporting, the trend estimate for May payrolls was revised to a gain of 168,000 (previously 163,000), June is 155,000 and July is 146,000.

Unemployed Increasingly Exit Headline Labor Force. The headline U.3 unemployment rate dropped a statistically insignificant notch to 8.1% in April, from 8.2% in March, but the “good” news was anything but good. The declining pace of headline unemployment reflected an accelerating increase in the number of the headline unemployed giving up looking for work, because there were no jobs to be had.

The number of short-term discouraged workers increased by 103,000 in April, with the inclusive broader U.6 unemployment rate holding at 14.5% in April. The 103,000 pick up in the short-term discouraged workers, however, was net of those who rolled into long-term discouraged worker status (discouraged for more than a year) and simply disappeared from the government’s unemployment accounting. The SGS-Alternate Unemployment Measure, accordingly, notched higher in April to 22.3%, from 22.2% in March.

Construction Spending. The pattern of month-to-month change in construction spending, as of March 2012, remained one of ongoing bottom-bouncing or stagnation near the cycle low. The monthly changes were not statistically meaningful, with a decline in public spending slightly more than offsetting gains in both private residential and nonresidential construction. The numbers would be weaker, if adjusted for the effects of inflation.

Other Indicators. Some market gyrations in the last week were attributed to the regular hype over two series that are not particularly meaningful, at the moment. The issues with weekly new claims for unemployment insurance and the monthly purchasing managers survey have been discussed before (see for example the related discussion in Hyperinflation 2012), but are repeated briefly here for the benefit of those not familiar with the material.

Due to the Department of Labor’s general inability to seasonally adjust weekly numbers, meaningfully, the individual weekly jobless claims reports are not significant. Further, given the severity of the depth and length of the current economic collapse, layoff levels have tended to shrink along with the size of the surviving core workforce. Hence, levels of new claims that might have signaled a jobs turnaround in earlier downturns have little relevance at the moment.

The purchasing managers surveys have been heavily skewed by recession-battered seasonal adjustments that no longer reflect regular patterns of seasonal activity. Further, a number of weaker firms have been lost to the survey, due to financial impact of the severe recession, with the effect of the surviving reporting firms no longer being fully representative of industry activity.

Hyperinflation Watch—Systemic Stress Increases Anew. Broad money supply (M3) growth is slowing once again. In the systemic-solvency crisis of the last four-to-five years, I have found that to be a reasonable indicator of mounting stress within the banking system, and a precursor to some form of supportive monetary action by the Federal Reserve. I contend that the various actions taken by the Federal Reserve since the 2008 financial panic—including the purchases of mortgage backed securities and U.S. Treasuries in the two quantitative easings (QE-1 and QE-2)—were efforts at propping the banking system, under the cover of obtensibly trying to stimulate the U.S. economy.

Two new measures related to M3: M3 velocity (GDP/M3) and a systemic-confidence indicator in the form of the M3 to M2 ratio, are introduced below, following details of the April M3 growth indications.

Money Supply M3 (April 2012). With the caution of unusual weekly volatility seen in the Fed’s seasonally-adjusted weekly numbers around the April 17th tax date, and based on more than three weeks of reported data, the preliminary estimate of annual growth for the April 2012 SGS Ongoing-M3 Estimate—to be published tomorrow (May 5th) in the Alternate Data section—is on track to slow to 3.0% from a revised 3.7% (previously 3.4%) in March. The February revision was the result of multiple benchmark revisions—published by the Fed in the month—for various components series. With recent annual growth having peaked at 4.1% in January 2012, the upturn in annual growth that began in March 2011 not only has stalled, but also it appears to have begun to falter. Faltering broad money supply growth—in an environment of massive Federal Reserve accommodation—remains suggestive of an intensifying systemic-solvency crisis.

The seasonally-adjusted, month-to-month change estimated for April M3 likely will be near flat for a second month. The estimated month-to-month M3 changes, however, remain less reliable than the estimates of annual growth.

For April 2012, early estimates of year-to-year and month-to-month change follow for the narrower M1 and M2 measures (M2 includes M1, M3 includes M2). M2 for April is on track to show year-to-year growth of about 9.6%, versus a revised 9.8% (previously 9.6%) in March, with month-to-month growth estimated at roughly 0.3%, the same as in March. The early estimate of M1 for April shows year-to-year growth of roughly 18.1% versus an unrevised 17.4% in March, with month-to-month change a likely gain of 1.3% in April, versus a 0.2% gain in March. The relatively stronger annual growth rates in M1 and M2 continue to reflect an earlier shifting of funds out of M3 accounts into M1 and M2 accounts. Implications of that are discussed in the section on systemic confidence.

M3 Velocity Is on the Rise. A number of subscribers have raised questions as to the velocity of money, which is discussed in some detail in the 2008 Money Supply Special Report. Velocity simply is the number of times the money supply turns over in the economy in a given year, or the ratio in nominal terms (not adjusted for inflation) of GDP to the money supply. At present, the velocity of M2 is falling, but the velocity of M3 (using the SGS Ongoing-M3 Measure) is rising, as shown the following graph.

Velocity has theoretical significance, where, in combination with money supply growth, it can be a driving force behind inflation. Yet, since velocity is ratio of two numbers that are not particularly well or realistically measured, I do not put much weight in its actual estimate.

What I do find of interest, though, is why M3 and M2 are showing opposite patterns, and that is because the growth in M3 has been much weaker growth in M2. The reason behind the difference largely is that much of the M2 growth has reflected cash moving out of M3 categories—such as large time deposits and institutional money funds—into M2 or M1 accounts. Again, M3 contains M2, and M2 contains M1. The effect of the funds shift has no impact on M3, but it spikes M2 growth. The clarity of what is happening here is why I like to follow the broadest money measure available.

Systemic-Confidence Measure. The declining M3 measures are larger accounts that—at best—are only partially covered by government guarantees in normal times. Accordingly flight from the M3 accounts to the M2 level can reflect confidence in the banking system (other factors at play include interest rates). The preceding graph reflects the ratio of M3 to M2, which has not recovered from the plunge that began with the 2008 panic. The ongoing nature of the decline appears indicative of mounting systemic stress, or declining confidence, and well could be suggestive of a perceived, growing need by Mr. Bernanke to provide new liquidity to the system.

In the event of something along the lines of the introduction of a QE-3, global reaction likely would be taken out against the U.S. dollar. Risks ahead included a dollar selling panic that could trigger or accompany a potential loss of the U.S. dollar’s global currency reserve status.

Otherwise, in the context of the updated economic background published in Special Commentary No. 426 and Special Commentary No. 429 on consumer liquidity, and with full consideration of other economic, inflation and financial-market developments since the January 25, 2012 publication of the hyperinflation report, the broad economic, inflation and hyperinflation outlooks discussed in Hyperinflation 2012 have not changed.

__________

REPORTING DETAIL

EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT (April 2012)

Despite Decline in Headline Unemployment Rate, Household-Survey Employment Declined for Second Month. Underlying economic reality is starting to catch-up with the reporting of monthly labor conditions. The decline in headline unemployment reflected an accelerating movement of the headline unemployed to discouraged-worker status, a category that jumped by 103,000 in April. Headline payroll employment disappointed consensus expectations for a second month. These developments will start moving the consensus outlook towards weaker economic reporting in the near-term.

PAYROLL SURVEY DETAIL. The BLS reported today (May 4th) a statistically-insignificant, seasonally-adjusted April 2012 month-to-month payroll employment gain of 115,000 (a gain of 168,000 jobs before prior-period revisions) +/- 129,000 (95% confidence interval). The March payroll gain was revised to 154,000 (previously 120,000).

In terms of year-to-year change, the unadjusted April 2012 annual growth rate slipped to a five-month low of 1.32%, from a revised 1.55% (previously 1.50%) in March.

The following graphs of year-to-year unadjusted payroll change had shown a slowly rising trend in annual growth into 2011, which primarily reflected the still-protracted bottom-bouncing in the payroll series. That pattern of growth flattened out in late-2011, as shown in the first graph of the near-term detail in year-to-year change, and it has started to slow. The softer April 2012 number may have reflected some corrective adjustment to the somewhat stronger data seen in the December to March period.

As shown in the longer-term graph (historical detail back to World War II), with the bottom-bouncing of recent years, current annual growth has recovered from the post-World War II record 5.06% decline in August 2009, which was the most severe annual contraction seen since the production shutdown at the end of World War II (a trough of a 7.59% annual contraction in September 1945). Disallowing the post-war shutdown as a normal business cycle, the August 2009 annual decline remains the worst since the Great Depression, yet the current level of employment is far from any recovery.

The regular graph of seasonally-adjusted payroll levels, which shows the current employment level well below its pre-2007 recession peak, is located in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary section.

Concurrent Seasonal Factor Distortions. The issues with the BLS’s concurrent seasonal factor adjustments and related inconsistencies in the monthly reporting of the historical time series are further discussed and detailed in the ShadowStats.com posting on May 2nd of Unpublished Payroll Data (announced in Commentary No. 434.)

Despite revisions in the monthly data each month that go back years, the BLS only publishes two months of revisions with each release (February and March in the current instance), so as not to confuse data users. As a result, the reported February-through-April seasonally-adjusted payroll data are not consistent with earlier reporting. Conceivably, the shifting and unstable seasonal adjustments could move 50,000 jobs or more from earlier periods and insert them into the current period as new jobs, without there being any overt evidence of that happening.

Incomplete and Inconsistent BLS Payroll Reporting. Three months have passed since the annual benchmark revisions to payroll employment, and the latest concurrent seasonal factors show renewed misreporting of the BLS’s own historical payroll levels, as well as ongoing instabilities in the BLS’s seasonal factors.

As discussed in prior writings (see Hyperinflation 2012, for example), seasonal-factor estimation for most economic series has been distorted severely by the extreme depth and duration of the economic contraction. These distortions are exacerbated for payroll employment data based on the BLS’s monthly seasonal-factor re-estimations and lack of full reporting.

Where the BLS recalculates the monthly seasonal factors each month for payroll employment, going back a number of years, outside of benchmarks, it only publishes the revised data for the last two months of reporting. The benchmark revision that accompanied the release of January 2012 payrolls, in theory, included a full update of the revised concurrent seasonally-adjusted data (actually it is off by a month or two). As plotted below, though, the latest revised (but not published by the BLS) adjusted payroll data already are showing increasingly volatile, monthly seasonal-adjustment distortions of up to 50,000 jobs per month, with previously-reported payroll employment being shifted from the first-half to the second-half of the year. If seasonal-adjustment factors were stable in month-to-month reporting, which they should be, then the graph of differences would be flat and at zero.

A further big issue remains that the month-to-month seasonally-adjusted payroll data have become increasingly worthless, with reporting errors likely now well beyond the official 95% confidence interval of +/- 129,000 jobs in the reported monthly payroll change. Yet the media and the markets tout the data as meaningful, usually without question or qualification.

Birth-Death/Bias Factor Adjustment. Despite the ongoing and regular overstatement of monthly payroll employment—as evidenced usually by regular and massive, annual downward benchmark revisions (2011 excepted)—the BLS generally adds in upside monthly biases to the payroll employment numbers. The process was created simply by adding in a monthly “bias factor,” so as to prevent the otherwise potential political embarrassment of the BLS understating monthly jobs growth. The “bias factor” process resulted from an actual such embarrassment, with the underestimation of jobs growth coming out of the 1983 recession. That process eventually was recast as the now infamous Birth-Death Model (BDM), which purportedly models the effects of new business creation versus existing business bankruptcies.

April 2012 Bias. The not-seasonally-adjusted April 2012 bias was a positive 206,000, versus a positive 90,000 in March, and versus a current estimation of a 172,000 upside bias in April 2011. The aggregate upside bias for the last 12 months was 525,000 (up from 491,000 in March), or a monthly average of 44,000 (previously 41,000) jobs created out of thin air, on top of some indeterminable amount of other jobs that are lost in the economy from business closings. Those losses simply are assumed away by the BLS as part of the BDM, as discussed below.

Problems with the Model. The aggregated upside annual reporting bias in the BDM reflects an ongoing assumption of a net positive jobs creation by new companies versus those going out business. Such becomes a self-fulfilling system, as the upside biases boost reporting for financial-market and political needs, with relatively good headline data, while often also setting up downside benchmark revisions for the next year, which traditionally are ignored by the media and the politicians. Where the BLS cannot measure the impact of jobs loss and jobs creation from employers starting up or going out of business, on a timely basis (within at least five years, if ever), such information is estimated by the addition of a bias-factor generated by the BDM.

Positive assumptions—commonly built into government statistical reporting and modeling—tend to result in overstated official estimates of general economic growth. Along with happy guesstimates, there usually are underlying assumptions of perpetual economic growth in most models. Accordingly, the functioning and relevance of those models become impaired during periods of economic downturn, and the current downturn has been the most severe—in depth as well as duration—since the Great Depression.

Indeed, historically, the BDM biases have tended to overstate payroll employment levels—to understate employment declines—during recessions. There is a faulty underlying premise here that jobs created by start-up companies in this downturn have more than offset jobs lost by companies going out of business. So, if a company fails to report its payrolls because it has gone out of business, the BLS assumes the firm still has its previously-reported employees and adjusts those numbers for the trend in the company’s industry.

Further, the presumed net additional “surplus” jobs created by start-up firms, get added on to the payroll estimates each month as a special add-factor. These add-factors are set now to add an average of about 44,000 jobs per month in the current year, but the actual overstatement of monthly jobs likely exceeds that number by a significant amount. With the underlying economy continuing to falter, I expect a significant downside benchmark revision for 2012 (based on the upcoming March 2012 benchmark), given current details of the BLS’s overly positive estimates. We are developing in-depth analyses of both the BLS’s seasonal-adjustment modeling and benchmarking process, which should be published in the near future. The detail on the seasonal-adjustment modeling was introduced on May 2nd (in Commentary No. 434, see Unpublished Payroll Data).

HOUSEHOLD SURVEY DETAILS. The once statistically-sounder household survey, which counts the number of people with jobs, as opposed to the payroll survey that counts the number of jobs (including multiple job holders more than once) showed a monthly employment decline in of 169,000, following a decline of 31,000 in March 2012. Still, the headline unemployment rate declined, as even more people gave up looking for work and were dropped from the government’s estimate of the headline labor force.

Note: Severe issues with monthly seasonal factors are ongoing and meaningfully cloud the significance of the reported monthly levels in the adjusted headline U.3 unemployment rate and other adjusted household-survey numbers. The data have been shifted by highly unstable seasonal factors that are artifacts of the severe and extraordinarily protracted downturn in U.S. economic activity (as well as distortions created by 2010’s census hiring and firing effects), not by the regular and stable seasonal patterns that were in place before the current economic crisis. Unlike the payroll or establishment series, the household survey does not use the concurrent seasonal factor adjustment series.

Unemployment Rates. The reported April 2012 seasonally-adjusted headline (U.3) unemployment rate declined by a statistically-insignificant 0.09 percentage point to 8.10% +/- 0.23%, versus March’s reported 8.19%. On an unadjusted basis, April’s U.3 unemployment rate was 7.7%, versus March’s 8.4%.

The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (they cannot find a full-time job).

The accounting for those working part-time due to economic reasons still is skewed heavily by bad seasonal factors, although there was a little corrective move in April reporting. The April U.6 unemployment rate held at a seasonally-adjusted 14.5%, the same as in March. The unadjusted April U.6 rate declined to 14.1% from 14.8% in March.

April Short-Term Discouraged Workers Count Jumped by 103,000. The headline unemployed increasingly are giving up looking for work, leaving headline U.3 unemployment category and being rolled into the U.6 measure as short-term “discouraged workers.” Although the number of short-term discouraged workers increased by 103,000 month-to-month in April (the count never is seasonally adjusted), that is net of the number of discouraged workers who fell from the U.6 category into the long-term discouraged worker category that defines the SGS-Alternate Unemployment Measure.

In 1994, during the Clinton Administration, “discouraged workers”—those who had given up looking for a job because there were no jobs to be had—were redefined so as to be counted only if they had been “discouraged” for less than a year. This time qualification defined away the long-term discouraged workers. The remaining short-term discouraged workers (less than one year) are included in U.6.

Adding the SGS estimate of excluded long-term discouraged workers back into the total unemployed and labor force, unemployment—more in line with common experience as estimated by the SGS-Alternate Unemployment Measure—notched higher to 22.3% in April, from 22.2% in March. The SGS estimate generally is built on top of the official U.6 reporting, and tends to follow its relative monthly movements. Accordingly, the SGS measure will suffer some of the current seasonal-adjustment woes afflicting the base series, such as recent distortions in adjusted reporting of part-time employment for economic reasons. There still should be catch-up reporting in the months ahead, since the series do not use the concurrent-seasonal-factor methodology that is used with the payroll employment series.

Nonetheless, there continues to be a noticeable divergence in the SGS series versus U.6. The reason for this is that U.6, again, only includes discouraged workers who have been discouraged for less than a year. As the discouraged-worker status ages, those that go beyond one year, fall off the government counting, and new workers enter “discouraged” status. Accordingly, with the continual rollover, the headline workers flow into the short-term discouraged workers counted in U.6 continue, and from U.6 into long-term discouraged worker status (SGS Measure) at has been an accelerating pace. See the Alternate Data tab for more detail.

As discussed in previous writings, an unemployment rate above 22% might raise questions in terms of a comparison with the purported peak unemployment in the Great Depression (1933) of 25%. The SGS level likely is about as bad as the peak unemployment seen in the 1973 to 1975 recession. The Great Depression unemployment rate was estimated well after the fact, with 27% of those employed working on farms. Today, less that 2% work on farms. Accordingly, for purposes of Great Depression comparison, I would look at the estimated peak nonfarm unemployment rate in 1933 of 34% to 35%.

CONSTRUCTION SPENDING (March 2012)

March Construction Continued Pattern of Low-Level Stagnation. Construction activity remained severely impaired, bouncing along at levels near the cycle lows. The Census Bureau reported on May 1st that the total value of construction put in place in the United States during March 2012 was $808.1 billion, on a seasonally-adjusted—but not inflation-adjusted—annual-rate basis. That estimate was up by a statistically-insignificant 0.1% (down by 0.1%, net of prior period revisions) +/- 1.6% (all confidence intervals are at a 95% level) from a downwardly revised $807.3 billion (previously $808.9) in February. In turn, February showed a revised 1.4% (previously 1.1%) decline from January.

Although construction was up by a statistically-significant 6.0% +/- 2.2% in March, the gain likely was more than covered by increases in construction costs. Year-to-year, February construction was up by a revised 5.6% (previously 5.8%).

Month-to-month changes are not statistically meaningful. The small aggregate decline in March construction reflected declining public spending, which more than offset small gains in the private sector.

As reflected in the accompanying graphs, on a monthly basis March private construction rose by 0.7% (0.9% before prior-period revisions), with residential construction up 0.7% (down 0.1% before prior-period revisions), and with nonresidential construction also up by 0.7% (up by 2.5% before prior-period revisions). March public construction for the month declined by 1.1% (down by 1.9% before prior-period revisions).

The annual benchmark revision for the series is due for release on July 2, 2012.

In line with the ongoing bottom-bouncing reported through March 2012 in construction spending, and suggestive of that pattern having continued in April, seasonally-adjusted April construction employment change remained stagnant. April construction jobs purportedly declined by 2,000 to a level of 5.558 million, from a revised 5.560 (previously 5.551) million in March, per the April payroll survey.

Week Ahead. Recognition of an intensifying double-dip recession as well as an escalating inflation problem remains sporadic. The political system would like to see the issues disappear until after the election; the media does its best to avoid publicizing unhappy economic news; and the financial markets will do their best to avoid recognition of the problems for as long as possible, problems that have horrendous implications for the markets and for systemic stability.

Until such time as financial-market expectations move to catch up fully with underlying reality, or underlying reality catches up with the markets, reporting generally will continue to show higher-than-expected inflation and weaker-than-expected economic results in the months and year ahead. Increasingly, previously unreported economic weakness should show up in prior-period revisions.

Trade Balance (March 2012). Due for release on Thursday, May 10th, the March trade deficit will provide one indication of revision pressures for the second reporting, first revision of first-quarter 2012 GDP, due for May 31st. A greater-than-expected widening in the March trade deficit—the most likely outcome—would place some downside revision pressure on the GDP series.

Producer Price Index—PPI (April 2012). April PPI data are due for release on Friday, May 11th. With oil prices down, on average, for the month of April, and with traditional seasonal-adjustment patterns further reducing the level of oil prices in the April PPI, any monthly increase in the PPI would come from spreading cost pressures in the broad, general economy. With MarketWatch.com indicating an early consensus of a 0.1% monthly gain in the April PPI, there is some risk of a downside surprise versus the consensus.

__________