No. 468: August Employment and Unemployment, M3

COMMENTARY NUMBER 468

August Employment and Unemployment, M3

September 7, 2012

__________

A Move to Open-Ended Monetization of Treasuries?

Payroll Jobs Down by 261,000, Household-Survey Employment Down by 86,000,

Since President Obama’s January 2009 Inauguration

BLS Did Not Publish Actual July-to-August Unemployment Rate Change

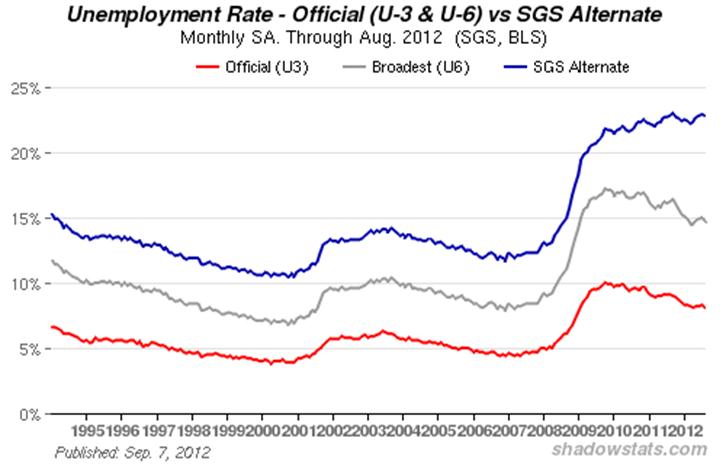

August Unemployment: 8.1% (U.3), 14.7% (U.6), 22.8% (ShadowStats.com)

M3 Annual Growth Notches Higher

Jump in Reported Inflation Likely in Week Ahead

__________

PLEASE NOTE: The next regular Commentary is scheduled for Thursday, September 13th, covering the July trade balance and August PPI. That will be followed by a Commentary on Friday, September 14th, covering August CPI, retail sales, industrial production and related series.

Best wishes to all — John Williams

Opening Comments and Executive Summary. Suggestions of mounting systemic-solvency issues have begun to surface in recent central bank activity and discussions, and that circumstance is worthy of a comment before getting into the August labor data and other economic numbers. Efforts are afoot to introduce open-ended buying of government bonds by the European Central Bank (ECB) and by the Federal Reserve. While the ECB effort already is “approved,” it may run into problems with the financial prudence demanded by the Bundesbank; the Fed suffers no such apparent constraint. With a lack of concern for financial propriety, born of necessity, the U.S. central bank likely will need and get such a bond-buying program in place, soon, with negative implications for the U.S. dollar and domestic inflation, as discussed in the Hyperinflation Watch section.

The August employment and unemployment data either were statistically insignificant or simply were meaningless on a month-to-month basis. Broadly, though, payrolls show that the economy is not recovering, while unemployment—from the standpoint of common experience—remains near a post-Great Depression high. Nonetheless, politics and the markets are putting unusual twists into the data and economic claims, as discussed in this section.

Construction spending continued its pattern of low-level stagnation in July, with unchanged August construction payrolls suggesting further stagnation in August (see Reporting Detail section).

Annual inflation in the July PCE deflator came in at 1.3%, below the Fed’s 2.0% target for a fourth month (see the Reporting Detail section). The recent slowing of annual inflation, however, is about to reverse, with higher energy, food and “core” prices suggesting a sharp spike in both headline monthly and annual August CPI inflation, due for release on Friday, September 14th (see the Week Ahead section).

Distorted Employment and Unemployment Reporting. With the presidential race formally underway, politics already is generating misleading claims. The Democrats, for example, claimed throughout their convention that the Obama Administration had created 4.5 million new jobs, later clarified as being private-sector jobs (ignoring roughly 560,000 government jobs lost primarily at the state and local government level during the same period). That measure, though, appears to have been taken from the trough of private-sector payroll employment reporting—in February 2010—well after the onset of President Obama’s term in office.

Measured from the time of the Obama inauguration (January 2009) through August 2012, reported total payroll employment actually declined by 261,000 jobs, while employment of individuals reflected in the household survey fell by 86,000. Where it is not reasonable to attribute job losses in the early months of the administration to Obama’s policies, the point here is that creative political statisticians can generate almost any kind of economic story they desire from the existing data. Where much of what is being reported in the economic numbers is not statistically meaningful to start with, statistics thrown around by the politicians need to be viewed with caution.

Reported August Unemployment Rate Decline Was Meaningless. As discussed in some detail in Commentary No. 451 and in Commentary No. 461, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) calculates the headline monthly unemployment rate independent of the previous calculation of the prior month’s unemployment rate. As a result, the published numbers are not comparable on a month-to-month basis, and the headline month-to-month changes are without meaning. In calculating the 8.1% August unemployment rate, for example, the BLS had to re-estimate the July number on a consistent basis. Yet, as per its standard practice, the BLS did not and will not publish the consistent prior-month number, even though the difference could be several-tenths of a percentage point. That would require publishing a revised July number, and the BLS does not want to “confuse” data users. So, July headline unemployment remained at 8.3% and the headline August unemployment rate dropped by a politically-happy two-tenths of a percentage point.

That two-tenths of a percentage point (actually 0.14% at the second decimal point) decline just as easily could have been an increase of that magnitude. Whatever today’s actual month-to-month change was never will be published in the normal course of business, and that opens the potential for direct political manipulation of the data.

The reporting issues carry across all the household-survey data. Seasonally-adjusted household-survey employment declined by 119,000 in August, after dropping by 195,000 in July. Due to the way the BLS data are prepared, those numbers simply are meaningless. In like manner, the decline in the broader, adjusted U.6 unemployment rate from 15.0% in July to 14.7% in August is without meaning.

Payroll Employment Growth Was Not Statistically Meaningful. The headline 96,000 gain in payroll employment was statistically-insignificant. Even so, the number received some boost from prior-period revisions (the gain was 55,000 versus initial July reporting), and that was before considering seasonal-factor distortions and the impact of the birth-death model. The adjusted July month-to-month change was revised to a 141,000 (previously 163,000) gain, while June month-to-month gain was revised to 45,000 (previously 64,000 and initially 80,000).

Preceding are the regular graphs of seasonally-adjusted payroll levels. The first, since 2000, shows detail of the current employment level well below the pre-2007 recession peak, as well as current payroll levels that still are holding minimally above the levels seen in 2000. The second graph is longer-term, showing historical payroll employment detail back to 1940.

Other Economic Releases. There have been several private economic releases within the last week.

Employment Related. The Conference Board’s online help-wanted index (new advertising) showed a second month-to-month decline in August, down by 3.2%, following a 7.3% month-to-month decline in July and an 8.9% increase in June. That recent downturn suggests some possible downside jobs pressure from weaker hiring, the otherwise usually positive offset to jobless claims.

The ISM’s purchasing managers (manufacturing) survey held at a contraction level, below 50.0, for the third month, at 49.6 in August, versus 49.8 in July and 49.7 in June. The employment index dropped to 51.6 in August, versus 52.0 in July and 56.6 in June. On the services side, the employment index has some meaning, but there the index rose to 53.8 August, from 49.3 in July. The ISM numbers have been disrupted meaningfully in the last several years by seasonal-adjustment distortions, as discussed in Hyperinflation 2012.

Consumer Confidence/Sentiment. The August estimates of the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment and the Conference Board’s consumer confidence [also shown in the prior Commentary] surveys were mixed in month-to-month direction, as shown in the accompanying graphs. The general outlook here has not changed. Both series are trending lower, and current reporting remains at levels that have been seen historically only at the depths of the worst recessions.

Hyperinflation Watch—Open-Ended Monetization of Treasuries? Developments of the last week are suggestive of central banks (specifically the Federal Reserve) moving into a position to provide open-ended monetization of government debt. These actions and discussions of same also are suggestive of a deepening global systemic-solvency crisis.

A September 3rd Bloomberg story, Fed Moves Toward Open-Ended Bond Purchases to Satisfy Bernanke, noted as a sideline to the Jackson Hole meeting that, “Four Fed presidents have come out in favor of an open-ended strategy for bond buying, with three calling for the program to begin now.” The four Fed presidents, per Bloomberg, were James Bullard of the St. Louis Fed, John Williams of San Francisco, Charles Evans of Chicago, and Eric Rosengren of Boston. The idea would be to authorize the Fed to buy Treasuries, as it deemed necessary, under the cover of trying to reduce the unemployment rate. Yet, no amount of bond buying is going to have meaningful positive impact on the unemployment rate.

That happy news was followed yesterday (September 6th) by the European Central Bank agreeing “to launch a new and potentially unlimited bond-buying program… [Reuters, Draghi gets ECB backing for unlimited bond-buying, September 6th].” The Reuters story noted the dissent of Bundesbank head Jens Weidmann, citing a Bundesbank statement that “[Weidmann] regards such [bond] purchases as being tantamount to financing governments by printing banknotes.”

Dr. Weidmann is correct in his assessment. Where Germany remains the dominant financial power in the euro, the fate of the just-announced program remains to be seen. For the Fed, however, an open-ended bond-purchasing program (effective monetization of U.S. Treasuries) appears inevitable. At such time as the program is enacted, global response likely will be taken out against the U.S. dollar and dollar-based paper assets. This indeed is the stuff of which inflationary “end of the world as we know it” scenarios can be constructed.

August M3 Money Supply Annual Growth at About 3.1%. Based on more than three weeks of reported data, the preliminary estimate of annual growth for the August 2012 SGS Ongoing-M3 Estimate—to be published tomorrow (September 8th) in the Alternate Data section—is on track to hit 3.1%, up from a revised 2.9% (previously 2.8%) in July. As usual, revisions to prior months were due primarily to Federal Reserve revisions to underlying data. Nonetheless, with recent annual growth having peaked at 4.2% in February 2012, the upturn in annual broad money growth that began in February 2011, had faltered and appears now to be leveling out. Such a pattern—in an environment of massive Federal Reserve accommodation—still remains suggestive of an intensifying systemic-solvency crisis.

The seasonally-adjusted, month-to-month change estimated for August 2012 M3 likely will be around 0.2%, versus 0.5% in July. The estimated month-to-month M3 changes, however, remain less reliable than the estimates of annual growth.

For August 2012, early estimates of year-to-year and month-to-month changes follow for the narrower M1 and M2 measures (M2 includes M1, M3 includes M2). Full definitions are found in the Money Supply Special Report. M2 for August is on track to show year-to-year growth of about 6.3%, versus 8.1% in July, with month-to-month growth estimated at roughly 0.3% in August, versus 0.8% in July. The early estimate of M1 for August shows year-to-year growth of roughly 10.3%, versus a revised 15.7% (previously 15.9%) in July, with month-to-month change a likely gain of 0.2% in August, versus a revised 2.8% (previously 3.0%) in July. The variability in year-to-year growth rates reflects sharp monthly gains a year ago in M1 and M2 that reflected a shifting of funds out of M3 accounts into the M1 and M2 accounts.

General Outlook Unchanged. Otherwise, general circumstances have not changed, and the text that follows is the same as in the prior Commentary. This summary will be updated with the September 14th Commentary. The detail in Special Report No. 445 (June 12th) updated the hyperinflation outlook and the outlook for U.S. economic, U.S. dollar, and systemic-solvency conditions. That Special Report supplemented Hyperinflation 2012 (January 25th), which remains the primary Commentary detailing the hyperinflation story. Those reports are suggested as background reading for new subscribers.

Official GDP reporting shows plunging economic activity from fourth-quarter 2007 to second-quarter 2009, with an ensuing upturn in activity that led to a full recovery as of fourth-quarter 2011, and that “recovery” has continued through second-quarter 2012 GDP reporting.

In contrast to GDP reporting—and in line with patterns seen in better-quality economic series—I contend that the economy began turning down in 2006, plunging in 2008 into 2009 and subsequently stagnating—bottom-bouncing—at a low level of activity, ever since. There has been no recovery since mid-2009, and the economic downturn now is intensifying once again. The renewed slowdown is evident in the current reporting of nearly all major economic series. Not one of those series shows a pattern of activity that confirms the recovery evident in the GDP series.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke recently observed that broad aggregate measures of the U.S. economy, such as GDP, do not appear to be reflecting the common experience of the general public. General experience suggests that the economy has not recovered. As shown in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary, the official recovery simply is a statistical illusion created by the government’s use of understated inflation in deflating the GDP, which overstates deflated economic growth (see also Special Report No. 445, Public Comment on Inflation).

The long-term fiscal solvency issues of the United States—where GAAP-based accounting shows annual deficits running in the $5 trillion range—are not being addressed, and the politicians currently running the government lack the political will to address those issues. That circumstance initially suggested a hyperinflation crisis by the end of this decade, but federal government and Federal Reserve actions—in response to the systemic-solvency crisis of 2008—accelerated the process, indicating a hyperinflation problem by no later than the end of 2014. The continuing economic downturn is intensifying the fiscal- and systemic-solvency problems, and public awareness of this should grow rapidly in the months ahead.

Neither economic nor systemic-solvency issues have been resolved by U.S. government or Federal Reserve actions. With the economy weak enough to provide cover for further Fed accommodation to the still-struggling banking system, the next easing by the Fed—and it should follow as needed to support the banking system—likely will lead to a massive dollar-selling crisis, and that will begin the process of a rapid upturn in domestic consumer inflation. A dollar-selling crisis, however, could begin at any time, triggered by any number of economic, sovereign-solvency or political issues.

__________

REPORTING DETAIL

EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT (August 2012)

Both Payroll and Household Numbers Remain Heavily Disrupted by Reporting Distortions. As noted last month, reporting of month-to-month changes in both payroll employment and the unemployment rate is of such poor quality that the headline labor data have become worthless as indicators of current economic activity. Problems with seasonal-factor distortions—created by the economic collapse and exacerbated by the use of concurrent seasonal factors—have widened the likely margins of reporting error in the payroll survey to something beyond the usual +/- 129,000 jobs at the 95% confidence level (see Hyperinflation 2012).

Due to the deliberate, inconsistent reporting of monthly unemployment rates (see Opening Comments and Executive Summary), the official 0.2 percentage point reported decline in the headline August unemployment rate was without meaning. Only the BLS knows what the actual change was, and it will not publish a hard number, on a consistent basis, until after the election. By then, today’s number will have been revised (but not re-reported) four times, where any revision that would happen to match today’s reporting would be purely coincidental. Whatever today’s actual month-to-month change was never will be published in the normal course of business, and that opens the potential for direct political manipulation of the data.

Separately, the headline 96,000 gain in payroll employment was statistically-insignificant. Even so, the number received some boost from prior-period revisions (the gain was 55,000 versus initial July reporting), and that was before considering seasonal-factor distortions and the impact of the birth-death model.

Nonetheless, these numbers will be pulled apart by the financial markets and politicians well beyond any potential significance in the numbers. To the extent that there is significance in the monthly reporting, it is that the economy is not in recovery and that unemployment—as viewed by common experience—remains at a level that rivals any other downturn of the post-Great Depression era.

PAYROLL SURVEY DETAIL. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported today (September 7th) a statistically-insignificant, seasonally-adjusted August 2012 month-to-month payroll employment gain of 96,000 (a gain of 55,000 before prior-period revisions) +/- 129,000 (95% confidence interval). [Concurrent-seasonal-factor distortions likely have widened the margin of reporting error—the 95% confidence interval—to meaningfully beyond the official +/-129,000.]

The adjusted July month-to-month change was revised to a 141,000 (previously 163,000) gain, while the June month-to-month gain was a revised 45,000 (previously 64,000, initially 80,000). If, however, the June change were counted on a consistent basis with the latest concurrent seasonal factor calculations, the revised June gain was 57,000. The BLS publishes two prior months of consistent data with concurrent-seasonally-adjusted payrolls, but no prior months of consistent data with the unemployment rate. This issue is discussed in the Concurrent Seasonal Factor Distortions section.

Separately, the BLS announced today that it would release the preliminary estimate of the payroll employment benchmark revision (based on March 2012 surveying) on Thursday, September 27th.

As described in Payroll Trends, the trend indication from the BLS seasonal-adjustment model is for a 104,000 payroll gain in September, based on today’s reporting. While the trend indication often misses actual reporting (the indication for August was a 122,000 gain, versus an actual 96,000 headline gain), it usually becomes the basis for the consensus outlook.

In terms of year-to-year change, the not-seasonally-adjusted growth in August 2012 payrolls was 1.38%, versus a downwardly revised 1.38% (previously 1.40%) in July, and a revised 1.30% (previously 1.31%) in June.

The following graphs of year-to-year unadjusted payroll change had shown a slowly rising trend in annual growth into 2011, which primarily reflected the still-protracted bottom-bouncing in the payroll series. That pattern of growth flattened out in late-2011, as shown in the first graph of the near-term detail in year-to-year change, and it has fluttered around a slightly lower level since April 2012.

As shown in the longer-term graph (historical detail back to 1940), with the bottom-bouncing of recent years, current annual growth has recovered from the post-World War II record 5.06% decline in August 2009, which remains the most severe annual contraction seen since the production shutdown at the end of World War II (a trough of a 7.59% annual contraction in September 1945). Disallowing the post-war shutdown as a normal business cycle, the August 2009 annual decline was the worst since the Great Depression. Still, even with small annual growth in the series since mid-2010, the current level of employment is far from reflecting any economic recovery.

The regular graph of seasonally-adjusted payroll levels since 2000, showing detail of the current employment level well below its pre-2007 recession peak, as well as a longer-term graph of the payroll employment level, showing historical detail back to 1940 and, in perspective, that payroll levels still are minimally above levels in 2000, are located in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary section.

Concurrent Seasonal Factor Distortions. Unreported, seasonally-adjusted monthly payroll numbers still are showing a shift of first-half of the year jobs to the second-half of the year, with the peak upside reporting effect due for October 2012, the last employment report before the November election.

Despite revisions in the monthly data each month that go back years, the BLS only publishes two months of revisions with each nonfarm payrolls release (June and July in the current instance), so as not to confuse data users. (The BLS publishes no revised data on a monthly basis for the household survey, despite similar seasonal-adjustment approach, as discussed in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary, and in Commentary No. 461, Commentary No. 451 and Commentary No. 453). As a result, the reported June-through-August 2012 seasonally-adjusted payroll data are not consistent with earlier reporting. Conceivably, the shifting and unstable seasonal adjustments could move 80,000 jobs or more from earlier periods and insert them into the current period as new jobs, without there being any published evidence of that happening. The following graph suggests that something along those lines happened in August, with similar effects due for September and October reporting.

The issues with the BLS’s concurrent seasonal factor adjustments and related inconsistencies in the monthly reporting of the historical time series are further discussed and detailed in the ShadowStats.com posting on May 2nd of Unpublished Payroll Data.

Note: Incomplete and inconsistent BLS payroll reporting continues. Seven months have passed since the annual benchmark revisions to payroll employment, and the latest concurrent seasonal factors show renewed misreporting of the BLS’s own historical payroll levels, as well as ongoing instabilities in the BLS’s seasonal factors.

As discussed in prior writings (see Hyperinflation 2012, for example), seasonal-factor estimation for most economic series has been distorted severely by the extreme depth and duration of the economic contraction. These distortions are exacerbated for payroll employment data based on the BLS’s monthly seasonal-factor re-estimations and lack of full reporting.

Where the BLS recalculates the monthly seasonal factors each month for payroll employment, going back a number of years, outside of benchmarks, it only publishes the revised data for the last two months of reporting. The benchmark revision that accompanied the release of January 2012 payrolls, in theory, included a full update of the revised concurrent seasonally-adjusted data (actually it is off by a month or two). In the preceding graph, though, the latest revised (but not published by the BLS) adjusted payroll data show increasingly volatile, monthly seasonal-adjustment distortions of up to 80,000 jobs per month, with previously-reported payroll employment being shifted from the first-half to the second-half of the year. If seasonal-adjustment factors were stable in month-to-month reporting, which they should be under normal circumstances, then the graph of differences would be flat and at zero.

Note: A further big issue remains that the month-to-month seasonally-adjusted payroll data have become increasingly worthless, with reporting errors likely now well beyond the official 95% confidence interval of +/- 129,000 jobs in the reported monthly payroll change. Yet the media and the markets tout the data as meaningful, usually without question or qualification.

Birth-Death/Bias Factor Adjustment. Despite the ongoing and regular overstatement of monthly payroll employment—as evidenced usually by regular and massive, annual downward benchmark revisions (2011 excepted)—the BLS generally adds in upside monthly biases to the payroll employment numbers. The process was created simply by adding in a monthly “bias factor,” so as to prevent the otherwise potential political embarrassment of the BLS understating monthly jobs growth. The “bias factor” process resulted from an actual such embarrassment, with the underestimation of jobs growth coming out of the 1983 recession. That process eventually was recast as the now infamous Birth-Death Model (BDM), which purportedly models the effects of new business creation versus existing business bankruptcies.

August 2012 Bias. The not-seasonally-adjusted August 2012 bias was a positive 87,000, versus a positive 52,000 in July 2012, and versus a current estimation of an 89,000 upside bias in August 2011. The aggregate upside bias for the last 12 months was 546,000 in August 2012, versus 548,000 in July. At present that is a monthly average of roughly 46,000 jobs created out of thin air, on top of some indeterminable amount of other jobs that are lost in the economy from business closings. Those losses simply are assumed away by the BLS as part of the BDM, as discussed below.

Problems with the Model. The aggregated upside annual reporting bias in the BDM reflects an ongoing assumption of a net positive jobs creation by new companies versus those going out business. Such becomes a self-fulfilling system, as the upside biases boost reporting for financial-market and political needs, with relatively good headline data, while often also setting up downside benchmark revisions for the next year, which traditionally are ignored by the media and the politicians. Where the BLS cannot measure meaningfully the impact of jobs loss and jobs creation from employers starting up or going out of business, on a timely basis (within at least five years, if ever), such information is estimated by the BLS along with the addition of a bias-factor generated by the BDM.

Positive assumptions—commonly built into government statistical reporting and modeling—tend to result in overstated official estimates of general economic growth. Along with happy guesstimates, there usually are underlying assumptions of perpetual economic growth in most models. Accordingly, the functioning and relevance of those models become impaired during periods of economic downturn, and the current downturn has been the most severe—in depth as well as duration—since the Great Depression.

Indeed, historically, the BDM biases have tended to overstate payroll employment levels—to understate employment declines—during recessions. There is a faulty underlying premise here that jobs created by start-up companies in this downturn have more than offset jobs lost by companies going out of business. So, if a company fails to report its payrolls because it has gone out of business, the BLS assumes the firm still has its previously-reported employees and adjusts those numbers for the trend in the company’s industry.

Further, the presumed net additional “surplus” jobs created by start-up firms, get added on to the payroll estimates each month as a special add-factor. These add-factors are set now to add an average of about 46,000 jobs per month in the current year, but the actual overstatement of monthly jobs likely exceeds that number by a significant amount. With the underlying economy continuing to falter, I expect a significant downside benchmark revision for 2012 (based on the upcoming March 2012 benchmark that will be published in 2013), given current details of the BLS’s overly positive estimates. The BLS will publish an initial estimate of that benchmark revision on September 27th.

HOUSEHOLD SURVEY DETAILS. As discussed in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary and early writings such as Commentary No. 461, seasonally-adjusted month-to-month comparisons of components in the household survey having no meaning other than from the impact they have as hyped by the media, Wall Street and election-year politicians. The 0.2 percentage-point decline reported in the August headline unemployment rate could have been that, by coincidence, or the headline number just as easily could have shown a 0.2 percentage-point increase or no change at all. There is no way to tell, given current BLS reporting policies; the BLS calculates but does not report consistent data, as part of its standard monthly estimation process.

With that as background, following are the meaningless seasonally-adjusted numbers and absolutely worthless month-to-month comparisons, that will cause today’s markets to gyrate, will excite the popular press and will lead the political candidates to pontificate. Separately, at least the not-seasonally-adjusted numbers are consistent in their preparation.

Headline Household Employment. Based on the August household survey, which counts the number of people with jobs, as opposed to the payroll survey that counts the number of jobs (including multiple job holders more than once), August 2012 employment fell by 119,000, following an employment decline of 195,000 in July. As just discussed above, though, the seasonally-adjusted monthly change here is without significance, due to the underlying data not being comparable on a moth-to-month basis.

Unemployment Rates. The reported August 2012 seasonally-adjusted headline (U.3) unemployment rate of 8.11% was down by a rounded 0.1 percentage point, not the headline 0.2 percentage point, when compared at the second decimal place, versus the 8.25% unemployment rate that was separately and inconsistently estimated for July. The official +/- 0.23 percentage-point 95% confidence interval for the headline number is meaningless in the context as discussed above, where the headline monthly change cannot be calculated due to underlying data inconsistencies. On an unadjusted basis, August’s U.3 unemployment rate was 8.2%, versus July’s 8.6%.

The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (they cannot find a full-time job). The August U.6 unemployment rate declined to a seasonally-adjusted 14.7%, versus 15.0% in July. The unadjusted August U.6 rate declined to 14.6%, from 15.2% in July.

Discouraged Workers. The count of short-term discouraged workers (never seasonally-adjusted) eased to 844,00 in August from, 852,000 in July. The published number reflects the balance of the headline unemployed—increasingly giving up looking for work—leaving the U.3 unemployment category and being rolled into the U.6 measure as short-term “discouraged workers,” versus those moving from short-term status into the netherworld of long-term discouraged-worker status. It is the long-term discouraged worker category that defines the SGS-Alternate or ShadowStats.com Unemployment Measure.

In 1994, during the Clinton Administration, “discouraged workers”—those who had given up looking for a job because there were no jobs to be had—were redefined so as to be counted only if they had been “discouraged” for less than a year. This time qualification defined away the long-term discouraged workers. The remaining short-term discouraged workers (less than one year) are included in U.6.

Adding the SGS estimate of excluded long-term discouraged workers back into the total unemployed and labor force, unemployment—more in line with common experience as estimated by the SGS-Alternate Unemployment Measure—notched lower to 22.8% in August, from 22.9% in July. The SGS estimate generally is built on top of the official U.6 reporting, and tends to follow its relative monthly movements. Accordingly, the SGS measure will suffer some of the current seasonal-adjustment woes afflicting the base series.

CAUTION: Month-to-month comparisons of the various unemployment rates are meaningless

due to deliberate inconsistencies in BLS reporting.

There continues to be a noticeable divergence, however, in the ShadowStats.com series versus U.6. The reason for this is that U.6, again, only includes discouraged workers who have been discouraged for less than a year. As the discouraged-worker status ages, those that go beyond one year fall off the government counting, and new workers enter “discouraged” status. Accordingly, with the continual rollover, the flow of headline workers continues into the short-term discouraged workers (U.6), and from U.6 into long-term discouraged worker status (ShadowStats.com Measure), at what has been an accelerating pace. The aggregate August data show an increasing rate of individuals dropping out of the headline (U.3) labor force. See the Alternate Data tab for more detail.

As discussed in previous writings, an unemployment rate nearing 23% might raise questions in terms of a comparison with the purported peak unemployment in the Great Depression (1933) of 25%. The SGS level likely is about as bad as the peak unemployment seen in the 1973 to 1975 recession. The Great Depression unemployment rate was estimated well after the fact, with 27% of those employed working on farms. Today, less that 2% work on farms. Accordingly, for purposes of Great Depression comparison, I would look at the estimated peak nonfarm unemployment rate in 1933 of 34% to 35%.

CONSTRUCTION SPENDING (July 2012)

Construction Spending Activity Continued to Bottom-Bounce in July. The trend of stagnation in construction spending at low levels of activity continued in July. The Census Bureau reported September 4th, that the total value of construction put in place in the United States during July 2012 was $834.4 billion, on a seasonally-adjusted—but not inflation-adjusted—annual-rate basis. That estimate was down for the month by a statistically-insignificant 0.9% +/- 2.1% (all confidence intervals are at a 95% level), from an upwardly revised $842.2 billion (previously $842.1 billion) in June. The monthly gain for June versus May was an unrevised 0.4%.

Although total construction spending was up year-to-year by a statistically-significant 9.3% +/- 2.7% in July, the gain likely was more than covered by increases in construction costs. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) still underestimates the year-to-year inflation in “structures” at 4.0% (just revised from 3.9%) for second-quarter 2012. Year-to-year, June 2012 construction was up by an unrevised 7.0%.

The insignificant 0.9% decline in monthly construction spending included a 0.4% drop in July public construction spending, which remained unchanged in June. July private construction fell by 1.2% in the month, versus a 0.6% (previously 0.7%) monthly gain in June.

As reflected in the accompanying graphs, July total construction fell by 0.9% for the month, with private residential construction down by 1.6%, private nonresidential construction down by 0.9% and public construction down by 0.4% for the month.

As shown in the preceding graph, in line with the ongoing bottom-bouncing reported through July 2012 in construction spending, and suggestive of continued stagnation in August, the seasonally-adjusted August construction employment level was 5.515 million, virtually unchanged versus a revised 5.514 million (previously 5.513 million) in July and 5.414 million in June, per the August payroll survey as published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

PERSONAL CONSUMPTION EXPENDITURE (PCE) DEFLATOR (July 2012)

July PCE Deflator Was Unchanged for the Month, with Year-to-Year Inflation at 1.3%. Published on August 30th by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the seasonally-adjusted July PCE deflator was unchanged at one-decimal point rounding (up by 0.01%) for the month, versus an unrevised 0.11% monthly gain in June.

Year-to-year PCE deflator growth slowed to 1.30% in July, versus an unrevised 1.52% in June. Annual PCE inflation held below the Fed’s 2.0% target for the fourth straight month. Nonetheless, below-target PCE inflation reporting should not become a protracted pattern here. The PCE deflator tends to follow the general direction of the CPI measures, which are due for a jump in August (see the Week Ahead section).

PCE Deflator versus Other Inflation Measures. In theory the PCE deflator measure should be virtually identical to the chain-weighted-CPI (C-CPI-U) (see Commentary No. 464 for details of the latest C-CPI-U and other inflation measures), and indeed it caught up with the C-CPI-U in the latest reporting, as shown in the preceding graphs. The July 2012 PCE deflator showed 1.3% year-to-year inflation, versus 1.5% in June. That compared with annual inflation in the July C-CPI-U at 1.3%, versus 1.6% in June; July CPI-U at 1.4%, versus 1.7% in June; July CPI-W at 1.3%, versus 1.6% in June; and the July SGS-Alternate (1980-Base) at 9.0%, versus 9.3% in June.

This “inflation targeting” effort by the Federal Reserve primarily is window-dressing for those in the markets who think the Fed really would move to contain inflation at the cost of impairing the still-fragile banking-system solvency. The Fed’s primary function remains keeping the banking system afloat, at any cost, as likely will be demonstrated again soon, when the U.S. central bank reacts to a re-intensifying systemic solvency crisis.

NOTE: The PCE deflator is the heavily massaged and modeled inflation rate for personal consumption expenditure, published on a monthly basis by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), and quarterly as part of the GDP release. The monthly series, which is a surrogate measure of consumer inflation—fully substitution and hedonic-based—generally tends to yield, and currently is yielding the lowest annual consumer inflation rate of the major series (see the preceding graphs of the PCE deflator versus the CPI-U and the C-CPI-U. Unlike the more widely followed CPI-U measure, which never is revised and is published on a seasonally unadjusted-basis, the PCE deflator is heavily revised for many years following initial reporting, and it is available only on a heavily-massaged, seasonally-adjusted basis.

Week Ahead. Market recognition of an intensifying double-dip recession has taken a somewhat stronger hold, at the moment, while recognition of a mounting inflation threat remains sparse. The political system would like to see the issues disappear until after the election; the media does its best to avoid publicizing unhappy economic news or to put a happy spin on the numbers; and the financial markets will do their best to avoid recognition of the problems for as long as possible, problems that have horrendous implications for the markets and for systemic stability.

Until such time as financial-market expectations catch up fully with underlying reality, or underlying reality catches up with the markets, reporting generally will continue to show higher-than-expected inflation and weaker-than-expected economic results in the months and year ahead. Increasingly, previously unreported economic weakness should continue to show up in prior-period revisions.

U.S. Trade Balance (July 2012). The July 2012 trade deficit detail will be released on Tuesday, September 11th. The U.S. trade deficit continues in fundamental deterioration, with the effect that the July number has a fair shot of deteriorating by more than market expectations. A deteriorating deficit has a negative impact on GDP growth. A significantly wider deficit in July (or June in revision) would tend to put downside pressure on third-quarter (or second-quarter) GDP estimates, while a significant narrowing in the deficit would tend to boost the GDP. The general trend here going forward, again, though, likely will be for trade deterioration and net negative impact on the GDP estimates.

Producer Price Index—PPI (August 2012). The August 2012 PPI is scheduled for release by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on Thursday, September 13th, and should show a strong gain. Depending on the oil contract followed, oil prices rose by seven-to-elven percent on average in August. The gain in related energy prices should be supplemented somewhat by seasonal adjustments that tend to boost energy prices at this time of year. Food prices also are on the rise, which in combination with still relatively strong “core” inflation should generate something of a jump (likely above consensus) in wholesale prices for August.

Consumer Price Index—CPI (August 2012). The release by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of the August 2012 CPI numbers is scheduled for Friday, September 14th. The headline CPI inflation rate is due for a sharp jump on both a monthly and annual basis, reflecting rising energy, food and “core” inflation, with headline inflation reporting likely stronger than market expectations.

Of particular import, unadjusted monthly average gasoline prices rose by 8.1% in August 2012 (Department of Energy). Consider that August seasonal-adjustment factors tend to boost energy price inflation, where an unadjusted 6.8% monthly decline in August 2011 gasoline prices was turned into a 1.9% increase by the seasonal adjustments of that month. The BLS can use its “intervention analysis” to mute some of the seasonal adjustment impact, but the contribution of gasoline prices to the August headline CPI inflation still should be significant.

Year-to-year total CPI-U inflation would increase or decrease in August 2012 reporting, dependent on the seasonally-adjusted monthly change, versus the 0.33% gain in the seasonally-adjusted monthly level reported for August 2011. I use the adjusted change here, since that is how consensus expectations are expressed. To approximate the annual unadjusted inflation rate for August 2012, the difference in August’s headline monthly change (or forecast of same) versus the year-ago monthly change should be added to or subtracted directly from the July 2012 annual inflation rate of 1.41%. For example, if the headline monthly inflation number for August 2012 were 0.8%, then the year-to-year or annual inflation rate for August would increase to roughly 1.9%.

Retail Sales (August 2012). Scheduled for release on Friday, September 14th, by the Census Bureau, headline August 2012 retail sales likely will surprise market expectations on the downside, with any gains more than accounted for by higher inflation. Structural liquidity problems besetting the consumer should continue to cap consumption growth at a level below the pace of inflation. With the August CPI-U likely to show a solid increase, real (adjusted-for-inflation) retail sales should contract for the month.

Industrial Production (August 2012). Due for release Friday, September 14th, by the Federal Reserve, the headline August 2012 industrial production number also should come in below market expectations. The latest GDP revision suggested that second-quarter inventory building had not been as strong as initially estimated, and the ISM’s purchasing managers survey has shown the manufacturing sector in decline for the three months through August, with an outright contraction in August production. Even with seasonal-factor distortions the industrial production number has a good chance of generating a negative reporting surprise, along with some downside revisions to earlier reporting.

__________