No. 741: July Employment and Unemployment, Money Supply M3

COMMENTARY NUMBER 741

July Employment and Unemployment, Money Supply M3

August 7, 2015

__________

July Employment Detail Showed a Sub-Par Jobs Gain, with the

Internal BLS Payroll-Growth Trend Falling below 200,000 for August

Suggestions of a Pending Downside Payroll-Benchmark Revision

Still No Full Recovery for Full-Time Employment

Flat Construction Employment Did Not Confirm the

Reported Construction-Spending Boom

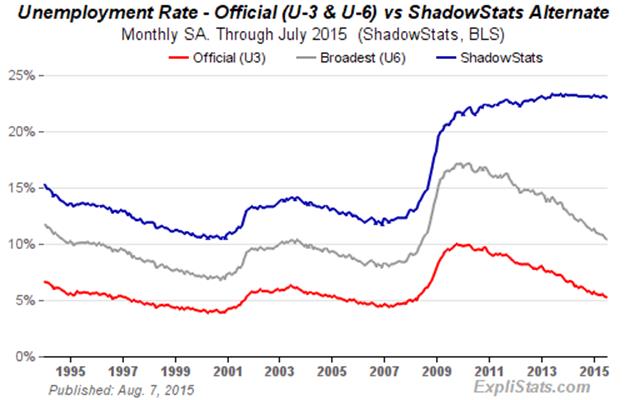

July 2015 Unemployment: 5.3% (U.3), 10.4% (U.6), 23.0% (ShadowStats)

M3 Money Supply Resurgent,

July Annual Growth Jumped to 5.6% from 5.2% in June

___________

PLEASE NOTE: A Special Commentary, on Monday, August 10th, will address the latest economic and inflation outlook, including risks to systemic and financial-market stability. The next regular Commentary on Monday, August 17th, will cover July nominal Retail Sales, Industrial Production and the Producer Price Index.

Best wishes to all — John Williams

OPENING COMMENTS AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Internal BLS Modeling Indicates Further Jobs-Growth Deterioration. Although July 2015 payroll growth came in near consensus in this morning’s (August 7th) reporting, the headline monthly gain of 215,000 jobs was at a level traditionally considered below normal for a healthy economy. The July reading was down from 231,000 in June 2015 and from 260,000 in May 2015. For comparison, consider that the average monthly payroll gain for all of 2014 was 260,000. Separately, though, the first four months of 2015 also suffered sub-par growth, and new indicators suggest that even worse reporting is ahead for the balance of the year, with weak prior growth estimates likely to be revised to the downside.

In the context of the latest detail in the July 2015 payroll estimation and related seasonal-adjustment modeling by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the trend generated by the BLS model now shows headline payroll growth slowing to 198,000 for August 2015 (it had been at 243,000 for July). Consensus and market expectations for August 2015 payroll growth should settle around the trend estimate, below the psychologically-important barrier of a 200,000 monthly jobs gain (see Trend in Reporting Detail).

Separately, the BLS has lowered recent upside monthly bias factors built into the Birth-Death Model (BDM). With more frequent, internal benchmarking, such suggests the BLS found it was overstating payrolls. That means reporting of even slower growth in the months ahead (lower upside biases), and a likely downside 2015 payroll-benchmark revision (see BDM section in Reporting Detail).

When headline growth in payroll employment slows, other key series also tend to do so, on a coincident or lagging basis. Series such as retail sales (a leading indicator) and industrial production (usually a coincident indicator), however, both have been leading the headline employment detail. Reduced consensus economic expectations, and downside reporting surprises to those expectations, should become increasingly commonplace. That would be in line with a multiple-dip economic collapse, discussed in Commentary No. 739.

Otherwise, the headline reporting for July 2015 payroll employment and unemployment were in line with market expectations, with minimal revisions to the payroll data. Of course, all of that was in the context of the usual reporting biases and distortions discussed in the opening paragraphs of the Reporting Detail section.

Full-Time Employment Has Yet to Recover Its Pre-Recession High. Usually discussed in these Commentaries is the contrast between the recovery in payroll employment, versus its pre-recession peak, and the lack of same for full-time employment. Noted in today’s Reporting Detail, the July 2015 payroll employment level was 3.7-million jobs above its pre-recession peak, while the level of July full-time employment remained 0.3-million shy of that benchmark.

Beyond excessive upside add-factor biases built into the monthly calculations (see the Birth-Death Model section), the problem remains that payroll employment counts the number of jobs, not the number of people who are employed. Much of that payroll "jobs" growth has been in part-time jobs (multiple and otherwise), many taken on for economic reasons, where full-time employment had been desired but could not be found. Full-time employment excludes the count of those employed with only part-time jobs, one or more. The following two graphs show some further contrast between the two employment measures.

The first graph shows the respective levels of full-time employment and payroll-employment, indexed to December 2007 = 100, the formal onset of the 2007 recession. As the economy collapsed, part of the loss in full-time employment was offset by a shift part-time employment, giving a relative boost to payroll levels. Full-time employment still has not recovered.

A similar pattern can be seen in the second graph, where the sharper decline in annual year-to-year change for full-time employment, and the respective greater relative drop in the level full-time employment never have been recovered, although current annual growth levels are close to the headline annual growth levels in payroll employment.

Today’s Missive (August 7th). The balance of today’s Opening Comments addresses the usual headline detail on the July labor market conditions.

The Hyperinflation Watch updates current monetary conditions, along with the initial estimate of the ShadowStats Alternate Measure of M3 Money Supply for July 2015. The revised Hyperinflation Outlook Summary section has expanded and evolved into a Special Commentary, which will be published on Monday (August 10th). Elements of the new report have been discussed piecemeal in recent Opening Comments (see Commentary No. 737, Commentary No. 738 and Commentary No. 739, for example), but the basic outlook and underlying fundamentals have not changed. The most-recent version of the summary outlook remains available in Commentary No. 735.

The Week Ahead section previews next week’s reporting of nominal Retail Sales, Industrial Production and the Producer Price Index (PPI).

Employment and Unemployment—July 2015—Near Consensus but with Weakening Jobs Growth. Discussed in the opening paragraphs, the outlook for payroll employment is slowing markedly, consistent with what eventually will be recognized as a renewed contraction in an ongoing, multiple-dip downturn. Separately, although the headline unemployment rate U.3 remains relatively low, it does not reflect the common experience of those dropped from the headline labor force because they could not find a job.

Payroll Employment Growth Has Slowed. In the context of minor upside revisions to the headline levels of May and June payrolls, the seasonally-adjusted, headline gain for July 2015 employment was 215,000 jobs, near consensus and below trend. Net of prior-period revisions, the July gain was 229,000 jobs.

The headline 215,000 jobs increase followed a revised gain of 231,000 in June, and a revised increase of 260,000 in May. The 260,000 jobs gain in May, however, really was 262,000, on a consistent-reporting basis. Although headline monthly gains prior to June deliberately are misreported by the BLS, given its use of, and publication practices with concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors, the actual earlier numbers can be calculated using material available from the BLS. The differences between the headline and actual numbers, though, usually are much more than the 2,000 jobs seen in the May detail.

Not-seasonally-adjusted, however, year-to-year change in payroll employment is untouched by the concurrent-seasonal-adjustment issues, so the monthly comparisons of year-to-year change at least are reported on a consistent basis. Yet, a possible redefinition of the series—not the standard benchmarking process in 2014—appears to be in play, on top of the prior distortions from the 2013 benchmarking, as was discussed in Commentary No. 598.

With the 2014 benchmarked surges built into recent headline payroll activity, patterns of year-to-year growth in unadjusted payrolls also moved higher, setting a post-recession high of 2.39% in February 2015. Such was the strongest annual growth since June 2000 (another recession), but subsequent annual growth has slowed. Year-to-year nonfarm payroll growth in July 2015 was 2.13%, versus a revised 2.11% in June, and an unrevised 2.20% in May 2015, 2.21% in April 2015, and 2.25% in March 2015.

Counting All Discouraged Workers, July 2015 Unemployment Was About 23.0%. Discussed frequently in these Commentaries on monthly unemployment conditions, what removes headline-unemployment reporting from common experience and broad, underlying economic reality, simply is definitional. To be counted among the headline unemployed (U.3), an individual has to have looked for work actively within the four weeks prior to the unemployment survey. If the active search for work was in the last year, but not in the last four weeks, the individual is considered a "discouraged worker" by the BLS, not counted in the headline labor force. ShadowStats defines that group as "short-term discouraged workers," as opposed to those who, after one year, no longer are counted by the government and enter the realm of "long-term discouraged workers," as counted by ShadowStats (see the extended comments in the ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Measure in the Reporting Detail section).

In the ongoing economic collapse into 2008 and 2009, and the non-recovery thereafter, the broad drop in the U.3 unemployment rate from its headline peak of 10.0% in 2009 to today’s 5.3% has been due largely to unemployed giving up looking for work—being redefined out of headline reporting and the labor force, as discouraged workers—not so much from the unemployed finding new and gainful employment.

At the same time as new discouraged workers move regularly from U.3 into U.6 unemployment accounting, those who have been discouraged for one year are dropped from the U.6 measure. As a result, the U.6 measure has been declining along with U.3 for some time, but those being pushed out of U.6 still are counted in the ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Measure, which has remained steady, at or near its historic-high rate for the last couple of years.

Moving on top of U.3, the broader U.6 unemployment rate—the government’s broadest unemployment measure—includes only the short-term discouraged workers (those marginally attached to the labor force). The still-broader ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure includes an estimate of all discouraged workers, including those discouraged for one year or more, as the BLS used to define and measure the series, before 1994.

Again, when the headline unemployed become "discouraged," they are rolled over from U.3 to U.6. As the headline, short-term discouraged workers roll over into long-term discouraged status, they move into the ShadowStats measure, where they remain. Aside from attrition, they are not defined out of existence for political convenience, hence the longer-term divergence between the various unemployment rates. The resulting difference here is between headline-June 2015 unemployment rates of 5.3% (U.3) and 23.0% (ShadowStats).

The graph immediately following reflects headline July 2015 U.3 unemployment at 5.26%, versus 5.28% in June; headline July U.6 unemployment at 10.39%, versus 10.52% in June; and the headline July ShadowStats unemployment estimate at 23.0%, versus 23.1% in June. Again, the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment series is built upon the BLS reporting of seasonally-adjusted U.3 and U.6 series, and correspondingly, is affected by the reporting and annual seasonal adjustments to those underlying series.

The next three graphs reflect longer-term unemployment and discouraged-worker conditions. The first graph is of the ShadowStats unemployment measure, with an inverted scale. The higher the unemployment rate, the weaker will be the economy, so the inverted plot tends to move in tandem with plots of most economic statistics, where a lower number means a weaker economy.

Shown in the second graph, the inverted-scale of the ShadowStats unemployment measure also tends to move with the employment-to-population ratio. Discouraged workers are not counted in the headline labor force, which generally continues to shrink. The labor force containing all unemployed (including total discouraged workers) plus the employed, however, tends to be correlated with the population, so the employment-to-population ratio tends to be something of a surrogate indicator of broad unemployment, and it has a strong correlation with the ShadowStats unemployment measure.

The Ongoing Good-Fed Chair versus Bad-Fed Chair Routine. The third graph (following) plots the labor-force participation rate (headline labor force as a percent of population), a series viewed by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen as a meaningful indicator of the health of the labor market. She has mentioned a needed improvement in labor-market health as a precondition to raising interest rates, but such conditions continue under debate. The participation rate deteriorated, minimally, to a new low in July 2015. Such means, in theory, that the Fed still is not about to tighten monetary conditions, despite other occasionally "happy" headline economic data, if the Fed Chair still is to be believed. The continuing Good-Fed Chair, Bad-Fed Chair games are played regularly, as needed for the benefit of the U.S. financial markets.

The labor force used in the participation rate calculation is the headline employment plus U.3 unemployment. As with the prior graph of employment-to-population, its holding at a post-1994 low in current reporting is another indication of problems with long-term discouraged workers, the loss of whom continues to shrink the headline (U.3) labor force, and the plotted ratio. These three graphs reflect detail back to the 1994 redefinitions of the Household Survey. Before 1994, data consistent with June’s reporting simply are not available, irrespective of protestations to the contrary by the BLS.

Headline Unemployment Rates. Headline July 2015 unemployment rate (U.3) declined by 0.02-percentage point to 5.26%, from 5.28% in June. That change is meaningless, though, in the context of the non-comparability of the headline monthly data, which results from the BLS’s reporting methodology and use of concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors. Those issues are separate from recent official questions raised as to falsification of Current Population Survey results, from which the unemployment detail ultimately is derived (see discussion in Household Survey section of the Reporting Detail).

On an unadjusted basis, the unemployment rates are not revised and at least are consistent in reporting methodology. July’s unadjusted U.3 unemployment rate rose to 5.55% (rounds to 5.6%), versus 5.46% in June.

The negligible change in the seasonally-adjusted, headline July U.3 unemployment rate reflected minimal changes in the number of unemployed individuals [down by 33,000 (-33,000)] and in the labor force [up by 69,000], differences that were meaningless in terms of statistical significance, and in terms of the regular non-comparability of the month-to-month, seasonally-adjusted headline numbers in this series.

Nonetheless, new discouraged and otherwise marginally-attached workers always are moving into U.6-unemployment accounting from U.3, while those who have been discouraged for one year continuously are dropped from the U.6 measure. As a result, the U.6 measure has been easing along with U.3, for a while, but those being pushed out of U.6 still are counted in the ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Measure, which has remained stable.

U.6 Unemployment Rate. The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (i.e., they cannot find a full-time job).

With no change in the underlying seasonally-adjusted U.3 rate, a continuing decline in the adjusted number of people working part-time for economic reasons and a continuing increase in unadjusted discouraged workers and the balance of those marginally attached to the workforce, headline July 2015 U.6 unemployment eased to 10.39% from 10.52% in June. The unadjusted U.6 was at 10.75% (rounds to 10.7%) in July, versus 10.82% in June.

ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Estimate. Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the still-growing ranks of excluded, long-term discouraged workers—a broad unemployment measure more in line with common experience—the July 2015 ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate, eased to 23.0%, versus 23.1% in June. The July reading was down from the 23.3% series high in 2013 (back to 1994). Again, the ShadowStats estimate generally shows the toll of long-term unemployed leaving the headline labor force.

[The Reporting Detail section includes further coverage of the

July employment and unemployment numbers.]

__________

HYPERINFLATION WATCH

MONETARY CONDITIONS

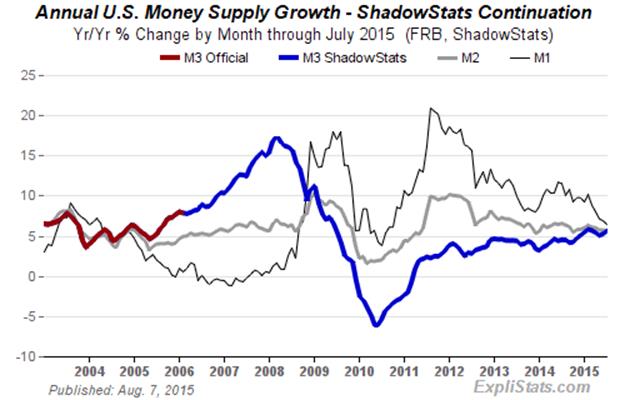

Annual Growth in Broad Money Supply Jumped to 5.6% in July. Late in 2014, the Federal Reserve ceased net new purchases of U.S. Treasury securities as part of its quantitative easing QE3, but its holdings of Treasury securities have remained stable, near record levels. Despite relative stability in the monetary base during the last year—plus-or-minus 5% around the St. Louis Fed’s estimated 12-month average of $4.0 trillion—annual growth in July 2015 money supply M3 rose to 5.6%, from an unrevised 5.2% in June, and a six-month low of 5.0% in May. The rising July growth rate was nearing the recent 68-month high of 5.8% seen in February 2015.

Money Supply M3 Annual Growth Tentatively Rose to 5.6% in July 2015, versus 5.2% in June. Year-to-year growth in July 2015 M3 (ShadowStats-Ongoing Measure) rose to 5.6%, versus an unrevised 5.2% annual gain in June 2015 and a near-term trough of 5.0% in May 2015. The rebounding pace of money-supply growth remained shy of the 5.8% near-term growth peak seen in February 2015, then the strongest showing since June 2009. Any revisions seen in the accompanying data are due to frequent, regular and irregular benchmark revisions by the Federal Reserve to the underlying monthly detail.

In 2015, the pattern of annual growth in M3 has closed in on that of M2, reflecting some shifting of funds in M1 and M2 into the larger M3 categories (ex-M2), where institutional money funds and large time deposits now are showing monthly growth patterns in excess of aggregate M2 monthly growth. That shift in funds accelerated in July.

After the series hit an interim near-term peak of 4.6% in each of the months of January, February and March 2013—the onset of expanded QE3—monthly year-to-year growth in M3 began to slow. Growth hit a near-term trough of 3.2% in January 2014, but that period of slowing growth had reversed fully as of May 2014, with annual growth recovering to 4.6%. Annual growth pulled back to 4.4% in June 2014, but rose again to 4.5% in July, easing back to 4.2% in September and October. Growth then jumped to 4.7% and 5.1%, respectively, in November and December 2014, rising to 5.4% in January 2015, and then hitting a five-year high of 5.8% in February. Again, annual growth had been falling off, since February, hitting 5.0% in May, but with an upside bounce to 5.2% in June, and now to 5.6% in July.

The seasonally-adjusted, early estimate of month-to-month change for July 2015 money supply M3 was roughly a gain of 0.9%, versus an unrevised gain of 0.4% in June 2015. Estimated month-to-month M3 changes, however, remain less reliable than are the estimates of annual growth.

Initial estimates for annual growth in M3, M2 and M1 for July 2015 have been updated on the Alternate Data tab of www.ShadowStats.com.

Growth for July M1 and M2. For July 2015, year-to-year and month-to-month changes follow for the narrower M1 and M2 measures (M2 includes M1; M3 includes M2). See the Money Supply Special Report for full definitions of those measures.

Annual M2 growth in July 2015 slowed to 5.7% from a revised 5.8% [previously 5.7%] gain in June 2015, with a month-to-month gain of about 0.6% in July versus 0.4% in June. For M1, year-to-year growth slowed to an initial estimate of 6.5% in July, versus a revised 6.9% [previously 6.8%] gain in June 2015, with a month-to-month increase of 0.5% in July, versus a revised 0.8% [previously 0.6%] monthly gain in June.

With the Monetary Base Staying Within Its Record-High Range, "Quantitative Easing" Remains Very Much in Play. Discussed in No. 692 Special Commentary: 2015 - A World Out of Balance, the Fed’s primary mission is to keep the banking system solvent and afloat, but that was not working, coming into the Panic of 2008. Quantitative easing was introduced in 2008 and went through a number of phases, as reflected in the size of, and growth in, the monetary base shown in the accompanying graphs. Where such monetary-base expansion normally would have translated into extraordinary growth in the money supply, it has not. Only as the Fed pulled back from aggressive asset purchases did M3 begin to show a little, fluctuating upside movement.

The extraordinary level of asset purchases by the Fed did not flow through to the broad economy, because banks did not lend into the normal flow of commerce, and there was no resulting significant upside movement in money supply, as a result. Instead, banks turned the funds back to the Fed as excess reserves, earning interest and providing support to the stock market. As part of this process, the Fed ended up monetizing the bulk of the U.S. Treasury’s funding needs during the period of active buying, paying back interest earned on the securities to the Treasury.

With the Fed having ceased purchases of new Treasury securities late in 2014 (maturing issues still are rolled over), the monetary base has continued its recent pattern of volatility at high-levels. Having set a record high level of $4.167 trillion in the two-week period ended April 15, 2015, the monetary base (Saint Louis Fed measure) has fluctuated around the average twelve-month $4.0 trillion level of the base, at $4.019 in the latest two-week period ended August 5th.

The Fed’s Treasury asset holdings effectively have continued at or near an all-time high, in the context of ongoing QE3. The expressed desire by some in the Fed to push interest rates higher, to more-normal levels, combined with a failing economy that should provide a practical restraint to such action, is suggestive of an economic-and-monetary system that continues to move beyond effective control of the U.S. central bank and the federal government, as will be discussed further in Monday’s (August 10th) Special Commentary.

HYPERINFLATION OUTLOOK SUMMARY

Broad Outlook Generally Is Unchanged: Economy Remains in Downturn; Dollar Faces Massive Decline with Ongoing Implications for Hyperinflation. The update to the Hyperinflation Outlook has expanded and evolved into a Special Commentary for Monday, August 10th. The major points are not altered fundamentally from the most-recent version of the Summary Outlook, found in Commentary No. 735, but the pending Special will be updated so to incorporate the latest details on the economy, global systemic instabilities and the gold circumstance, as discussed partially in various recent missives, including Commentary No. 737, Commentary No. 738 and Commentary No. 739.

Again, the U.S. economy remains in ongoing downturn, while the U.S. dollar still faces a massive decline, with implications for a meaningful upturn in inflation evolving into a great hyperinflationary crisis. Signs of systemic instability continue to intensify.

__________

REPORTING DETAIL

EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT (July 2015)

Employment Conditions Are Deteriorating. Unusual aspects of the reporting of July 2015 labor conditions suggested slowing payroll growth ahead and some downside shift in perhaps how the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) views current conditions. These factors are discussed in the opening paragraphs of the Opening Comments.

Otherwise, the headline reporting for July 2015 payroll employment (a headline gain of 215,000 jobs) and unemployment (U.3 held at 5.3%) were in line with market expectations, with minimal revisions to the payroll data. The headline details, however, were subject to the usual reporting biases and distortions.

Specifically, the headline Payroll Survey numbers were distorted by unreported inconsistencies in the historical data, as generated by BLS concurrent seasonal-factor adjustments (see Concurrent Seasonal Factor Adjustments). Separately, the jobs gains also were inflated meaningfully by the monthly add factors in the Birth-Death Model (BDM). With those biases likely well in excess of 200,000 jobs, actual July 2015 payrolls most likely fell month-to-month (see Birth-Death Model).

On the unemployment front, the BLS use of concurrent seasonal adjustment factors with the Household Survey, combined with an unwillingness to publish the new, consistent historical data as generated each month, leaves month-to-month comparisons of those data without meaning. Separately, issues remain as to falsification of the Household Survey data by employees of the Census Bureau, by those who have conducted the underlying Current Population Survey. Details on the related Congressional investigation were discussed in Commentary No. 669. Purportedly the investigation continues in the new Congress.

PAYROLL SURVEY DETAIL. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published the headline employment and unemployment data for July 2015, this morning, August 7th. In the context of minor upside revisions to the headline levels of May and June payrolls, the seasonally-adjusted, headline payroll gain for July was 215,000 jobs +/- 129,000 (95% confidence interval). Net of prior-period revisions, the gain in July payroll employment was 229,000 jobs.

The headline 215,000 increase in July payrolls followed a revised gain of 231,000 [previously 223,000] jobs in June, and an upwardly-revised increase of 260,000 [previously 254,000, initially 280,000] jobs in May. The 260,000 jobs gain in May, however, really was 262,000, on a consistent-reporting basis. Although the headline detail prior to June deliberately is misreported by the BLS, the earlier actual numbers can be calculated using material available from the BLS, and the differences usually are much more than the 2,000 seen in May.

Inconsistent, Non-Comparable and Deliberately-Misstated Monthly Changes for May 2015 and Before. Headline monthly payroll detail is not comparable with earlier months, back more than one month from the headline month, due to the BLS’s misuse of concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustments. Discussed in the later Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors section, the reporting fraud comes not from the adjustment process, itself, but rather from the Bureau deliberately not publishing a consistent headline history, where a new history is generated and available each month, along with the recalculation of the seasonal factors unique to creating the current month’s headline detail.

As a result, the headline 215,000 monthly gain in July 2015 payrolls and the revised 231,000 jobs gain in June were inconsistent with, and not comparable to, the revised headline May 2015 gain of 260,000. The gain consistent with the new headline July-based detail was 262,000 for May, some 2,000 more than the official number. Consistent with July’s reporting, the headline payroll gain for April 2015 now is 200,000, some 13,000 jobs higher than the official headline gain of 187,000, but the March 2015 monthly gain now is 100,000, some 19,000 jobs shy of the headline number. Such are regular misstatements of historical headline payroll activity by the BLS.

Headline differences can be more significant. For example, the headline monthly gain for November 2014 payrolls still is 423,000, but that never was true. That number came out of the 2014 benchmark reporting, including headline January 2015, but the November change versus October—consistent with the headline reporting of the time—was 337,000, some 86,000 less. With intervening revisions each month, the actual aggregate November and October levels have changed some, but now consistent with the headline July 2015 reporting and recalculations, the November 2014 versus October 2014 gain was 332,000, down by 91,000 (-91,000) versus the still 423,000 headline number. Consistent with June 2015 reporting, the actual difference in the headline versus actual gain was down by 90,000 (-90,000), down by 86,000 (-86,000) consistent with initial May 2015 reporting. The prior history changes each month, along with the new seasonal-factor calculations that determine the latest headline month’s numbers, with the consistent series explored fully in Commentary No. 695.

“Trend Model” for July 2015 Headline Payroll-Employment Change Takes Headline Growth Below 200,000. Discussed in Commentary No. 732, and as described generally in Payroll Trends, the trend indication from the BLS’s concurrent-seasonal-adjustment model—prepared by our affiliate www.ExpliStats.com—was for a July 2015 monthly payroll gain of 243,000, based on the BLS trend model structured into the actual headline reporting of June 2015. The detail here can be calculated independently, using material available from the BLS.

Consensus estimates tend to settle around the trend, but late-consensus expectations for July 2015 ranged from 212,000 [Bloomberg] to 220,000 (early-consensus at 215,000) [MarketWatch]. The 215,000-headline gain was close to the consensus estimates and below trend.

August 2015 Trend Estimate. Exclusive to ShadowStats subscribers, based on July 2015 reporting, the ExpliStats trend number calculations suggest a BLS-based headline gain of 198,000 for August 2015. August consensus expectations likely will settle around that level.

Confidence Intervals. Where the current employment levels have been spiked by misleading and inconsistently-reported concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustments, the reporting issues suggest that a 95% confidence interval around the modeling of the monthly headline payroll gain should be well in excess of +/- 200,000, instead of the official +/- 129,000. Even if the data were reported on a comparable month-to-month basis, other reporting issues would prevent the indicated headline magnitudes of change from being significant. Encompassing Birth-Death Model biases, the confidence interval more appropriately should be in excess of +/- 300,000.

July Construction-Payroll Growth Reporting Remained Flat, Not Supportive of Headline Construction Spending Gains. The following graph of construction-payroll employment updates the one in prior Commentary No. 740, covering June construction spending.

In theory, construction payroll levels should move closely with the inflation-adjusted aggregate construction spending series and the housing starts series (the latter measured in units rather than dollars). The downside May and June revisions to the headline construction jobs detail and the otherwise-flattening pattern of construction jobs growth ran counter to the headline detail and revisions for June and May construction spending.

The purported annualized gain of 25.7% in second-quarter 2015 real construction spending was not supported by the revised annualized headline growth of 2.6% [previously 2.7%] in second-quarter 2015 construction payrolls. Further, the pace of construction payroll growth in July suggested the annualized third-quarter growth rate has slowed to about 0.6%.

Following downside revisions to the levels of activity in May and June, headline July 2015 construction payrolls came in at 6.383 million jobs, up by 6,000 jobs from downwardly-revised level for June, and up by 3,000 from the initial headline reporting for June. As revised, the June 2015 detail showed an unrevised "unchanged" level versus May, but that was because May also was revised lower.

Headline construction-payroll numbers remain heavily biased to the upside (officially bloated by 6,000 jobs per month, unofficially at an order of magnitude of 20,000 jobs per month). Nonetheless, total July 2015 construction jobs remained down by 17.4% (-17.4%) from the April 2006 pre-recession series peak.

Historical Payroll Levels. Payroll employment is a coincident indicator of economic activity, and irrespective of all the reporting issues with the series, payroll employment formally regained its pre-recession high in 2014, despite the GDP purportedly having done the same three years earlier, back in 2011. Reflected in the next two graphs, headline payroll employment moved to above its pre-recession high in April 2014 (it had happened in May 2014, prior to the benchmark revisions published in February 2015), and it has continued to rise. Including the headline jobs gain of 215,000 in July 2015, headline payroll employment now is about 3.7-million jobs above the pre-recession peak.

The first two graphs show the headline payroll series, both on a shorter-term basis, since 2000, and on a longer-term historical basis, from 1940. In perspective, the longer-term graph of the headline payroll-employment levels shows the extreme duration of what had been the official non-recovery in payrolls, the worst such circumstance of the post-Great Depression era.

Beyond excessive upside add-factor biases built into the monthly calculations (see the Birth-Death Model section), the problem remains that payroll employment counts the number of jobs, not the number of people who are employed. Much of that payroll "jobs" growth is in multiple part-time jobs—many taken on for economic reasons—where full-time employment has been desired but could not be found (see the discussion and graphs in the Opening Comments).

Full-Time Employment versus Part-Time Payroll Jobs. Shown in the accompanying graph, the July 2015 level of full-time employment (Household Survey) still was 0.3-million shy of its precession high, compared to the headline payroll employment level that was 3.7-million above its pre-recession high. Again, the payroll count is of jobs, not people, where much of that payroll "jobs" growth has been in part-time, and in multiple part-time jobs, many taken on for economic reasons, where full-time employment was desired but could not be found, as separately discussed and graphed in the Opening Comments.

Full-time employment rose by a headline 536,000 in July 2015, which more than offset the headline June decline of 349,000 (-349,000), but it generally was in line with the nonsense, headline month-to-month volatility seen with a gain of 630,000 in May 2015, and a drop of 252,000 (-252,000) in April. Headline month-to-month volatility here is more a function of the instabilities from non-comparability of the headline, seasonally-adjusted monthly data (see the discussion in the Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors section), than it is as an indicator of actual month-to-month volatility in economic activity.

The graph of full-time employment excludes the count of those employed with only part-time jobs, one or more. Total employment, including those employed with part-time work, has recovered its pre-recession high, but it still is not close to the payroll reporting. Again, the Household Survey numbers count the number of people who have at least one job. The Payroll Survey simply counts the number of jobs (see Commentary No. 686 for further detail).

Annual Percent Change in Payrolls—Slower Growth. Not-seasonally-adjusted, year-to-year change in payroll employment is untouched by the concurrent-seasonal-adjustment issues, so the monthly comparisons of year-to-year change at least are reported on a consistent basis. Yet, a possible new redefinition of the series—not the standard benchmarking process in 2014—appears to be in play, on top of the prior distortions from the 2013 benchmarking (see Commentary No. 598).

With the 2014 benchmarked surges built into recent headline payroll activity, patterns of year-to-year growth in unadjusted payrolls also moved higher, setting a post-recession high of 2.39% in February 2015. Such was the strongest annual growth since June 2000 (another recession), but subsequent annual growth has slowed. Year-to-year nonfarm payroll growth in July 2015 was 2.13%, versus a revised 2.11% [previously 2.09%] in June, an unrevised 2.20% [initially 2.24%] in May 2015, an unrevised 2.21% in April 2015, and an unrevised 2.25% in March 2015.

With bottom-bouncing patterns of recent years, current headline annual growth has recovered from the post-World War II record decline of 5.02% (-5.02%) seen in August 2009, as shown in the accompanying graphs. That decline remains the most severe annual contraction since the production shutdown at the end of World War II [a trough of a 7.59% (-7.59%) annual contraction in September 1945]. Disallowing the post-war shutdown as a normal business cycle, the August 2009 annual decline was the worst since the Great Depression.

Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent-Seasonal Factors. Detailed in Commentary No. 694 and Commentary No. 695, there are serious and deliberate reporting flaws with the government’s seasonally-adjusted, monthly reporting of both employment and unemployment. Each month, the BLS uses a concurrent-seasonal-adjustment process to adjust both the payroll and unemployment data for the latest seasonal patterns. As new headline data are seasonally-adjusted for each series, the re-adjustment process also revises the monthly history of each series, recalculating prior, adjusted reporting for every month, going back five years, so as to be consistent with the new seasonal patterns that generated the current headline number.

Effective Reporting Fraud. The problem is that the BLS does not publish the monthly historical revisions along with the new headline data. As a result, current headline reporting is neither consistent nor comparable with prior data, and the unreported actual monthly variations versus headline detail can be large. The deliberately-misleading reporting effectively is a fraud. The problem is not with the BLS using concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors, it is with the BLS not publishing consistent data, where those data are calculated each month and are available internally to the Bureau.

Household Survey. In the case of the published Household Survey (unemployment rate and related data), the seasonally-adjusted headline July 2015 numbers are not comparable with the prior June 2015 data or any month before. Accordingly, the published headline detail as to whether the unemployment rate was up, down or unchanged in a given month is not meaningful, and what actually happened is not knowable by the public. Month-to-month comparisons of these popular numbers are of no substance, other than for market hyping or political propaganda.

The headline month-to-month reporting is made consistent in the once-per-year reporting of December data, when the annual revisions to the faux "fixed" seasonal adjustments are published. All historical comparability evaporates, though, with the ensuing month’s headline January reporting, and with each monthly estimate thereafter.

Payroll or Establishment Survey. In the case of the published Payroll Survey data (payroll-employment change and related detail), monthly changes in the seasonally-adjusted headline July 2015 data are comparable only with the headline changes in the June 2015 numbers, not with May 2015 or any earlier months. Due to the BLS modeling process, the historical data never are published on a consistent basis, even with publication of the annual benchmark revision, as discussed shortly.

No one seems to mind if the published earlier numbers are wrong, particularly if unstable seasonal-adjustment patterns have shifted prior jobs growth or reduced unemployment into current reporting, as often is the case, including the current July 2015 reporting, without any formal indication of the shift from the previously-published historical data.

The BLS does provide modeling detail for the Payroll Survey, allowing for third-party calculations, but no such accommodation has been made for the Household Survey. ShadowStats affiliate ExpliStats does such third-party calculations, and the detail of the differences between the current headline reporting and the constantly-shifting, consistent and comparable history are plotted in the accompanying graph.

The preceding chart details how far the monthly payroll employment data have strayed from being consistent with the most recent benchmark revision. The gray line shows that December 2014 pattern versus the 2013-benchmark revision, and the color-coded lines show the January to July 2015 patterns of distortion versus the 2014-benchmark. Due to several months of testing of the model, before the benchmark release, the BLS never publishes the historical data on a consistent basis.

A comparison of the heavy, dark-blue line (July 2015) with the thinner light-blue line (June 2015), shows shifts in seasonal factors in May through July 2014 numbers, with implied seasonality shifts for headline reporting in the May to July 2015 period. With the light- and dark-blue lines coming together in July 2014, there is an implied relative upside boost to the seasonal adjustments for July 2015. Despite the headline July 2015 jobs gain of a relatively-weak 215,000, headline July jobs gain would have been even softer, but for the shift in seasonals.

If the headline reporting were comparable and stable, month-after-month, all the lines in the graph would be flat and at zero. Here, with the payroll series, again, only the headline month and the prior month are consistent in terms of month-to-month reporting detail (headline June 2015 detail no longer is consistent nor comparable with data from May 2015 or earlier). Comparable with headline July and June reporting, May’s current headline jobs gain was understated by a minimal 2,000, although monthly discrepancies have been as large as 100,000 jobs (see the earlier section Inconsistent, Non-Comparable and Deliberately-Misstated Monthly Changes).

Birth-Death/Bias-Factor Adjustment. Despite the ongoing, general overstatement of monthly payroll employment, the BLS adds in upside monthly biases to the payroll employment numbers. The continual overstatement is evidenced usually by regular and massive, annual downward benchmark revisions (2011 and 2012 and 2014 excepted). As discussed in the benchmark detail of Commentary No. 598, the regular benchmark revision to March 2013 payroll employment was to the downside by 119,000, where the BLS had overestimated standard payroll employment growth.

With the March 2013 revision, though, the BLS separately redefined the Payroll Survey so as to include 466,000 workers who had been in a category not previously counted in payroll employment. The latter event was little more than a gimmicked, upside fudge-factor, used to mask the effects of the regular downside revisions to employment surveying, and likely is the excuse behind the increase in the annual bias factor, where the new category cannot be surveyed easily or regularly by the BLS. Elements tied to this likely had impact on the unusual issues with the 2014 benchmark revisions.

Abuses from the 2014 benchmarking are detailed in Commentary No. 694 and Commentary No. 695. With the headline benchmark revision for March 2014 showing a jobs understatement of 67,000, the BLS upped its annual add-factor bias by an even greater 161,000 for the year ahead, to 892,000. As has been standard BLS practice, there is no good political reason for risking a headline understatement of jobs growth.

Historically, the upside-bias process was created simply by adding in a monthly "bias factor," so as to prevent the otherwise potential political embarrassment to the BLS of understating monthly jobs growth. The "bias factor" process resulted from such an actual embarrassment, with the underestimation of jobs growth coming out of the 1983 recession. That process eventually was recast as the now infamous Birth-Death Model (BDM), which purportedly models the effects of new business creation versus existing business bankruptcies.

July 2015 Add-Factor Bias. The not-seasonally-adjusted July 2015 bias was a positive monthly add-factor of 83,000, down from the positive monthly add-factor of 109,000 in June 2015, and against a positive monthly add-factor of 122,000 in July 2014. The BLS has begun quarterly revisions to the biases, and the early cut still seems to a slowing pace of upside biases, versus prior reporting, coincident with what still appears otherwise to be a broad slowing in economic activity. Such a shift would mean that at least first-quarter 2015 jobs growth likely was overstated as seen internally in official calculations.

The revamped, aggregate upside bias for the trailing twelve months through July 2015 was 797,000, versus 836,000 in June and 856,000 in of May, but still higher than the pre-benchmarked level of 731,000 in December 2014. That was a rough-monthly average of 66,000 in July (versus 61,000 pre-benchmark) jobs created out of thin air, on top of some indeterminable amount of other jobs that are lost in the economy from business closings. Those losses simply are assumed away by the BLS in the BDM, as discussed below.

Problems with the Model. The aggregated upside annual reporting bias in the BDM reflects an ongoing assumption of a net positive jobs creation by new companies versus those going out of business. Such becomes a self-fulfilling system, as the upside biases boost reporting for financial-market and political needs, with relatively good headline data, while often also setting up downside benchmark revisions for the next year, which traditionally are ignored by the media and the politicians. The BLS cannot measure meaningfully the impact of jobs loss and jobs creation from employers starting up or going out of business, on a timely basis (within at least five years, if ever), or by changes in household employment that were incorporated into the 2014 redefined payroll series. Such information simply is guesstimated by the BLS, along with the addition of a bias-factor generated by the BDM.

Positive assumptions—commonly built into government statistical reporting and modeling—tend to result in overstated official estimates of general economic growth. Along with these happy guesstimates, there usually are underlying assumptions of perpetual economic growth in most models. Accordingly, the functioning and relevance of those models become impaired during periods of economic downturn, and the current, ongoing downturn has been the most severe—in depth as well as duration—since the Great Depression.

Indeed, historically, the BDM biases have tended to overstate payroll employment levels—to understate employment declines—during recessions. There is a faulty underlying premise here that jobs created by start-up companies in this downturn have more than offset jobs lost by companies going out of business. Recent studies have suggested that there is a net jobs loss, not gain, in this circumstance. So, if a company fails to report its payrolls because it has gone out of business (or has been devastated by a hurricane), the BLS assumes the firm still has its previously-reported employees and adjusts those numbers for the trend in the company’s industry.

Further, the presumed net additional “surplus” jobs created by start-up firms are added on to the payroll estimates each month as a special add-factor. These add-factors are set now to add an average of 66,000 jobs per month in the current year. In current reporting, the aggregate average overstatement of employment change easily exceeds 200,000 jobs per month.

HOUSEHOLD SURVEY DETAIL. Discussed in the earlier Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors section, seasonally-adjusted data from the monthly Household Survey simply are not comparable on a month-to-month basis. In this form, headline monthly changes in the unemployment-related numbers are virtually meaningless, good only for the market- or political-hype of the moment. The seasonal-adjustment process here restates the history of each series, each month, as unique adjustment factors determine the current month’s headline detail. Yet, when the BLS publishes the headline numbers, it does not publish the comparable revised history. Only the BLS, not the public, knows the actual, comparable monthly change in the seasonally-adjusted U.3-unemployment rate.

Separately, detailed in Commentary No. 669, significant issues as to falsification of the data gathered in the monthly Current Population Survey (CPS), conducted by the Census Bureau, have been raised in the press and investigated by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform and the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. Further investigation purportedly is underway with the new Congress. CPS is the source of the Household Survey used by the BLS in estimating monthly unemployment, employment, etc. Accordingly, the statistical significance of the headline reporting detail here is open to serious question.

Headline Unemployment Rates. The headline July 2015 unemployment rate (U.3) declined by 0.02-percentage point to 5.26%, from 5.28% in June. Technically, the headline July decline in U.3 was statistically-insignificant, where the official 95% confidence interval around the monthly change in headline U.3 is +/- 0.23-percentage point. The headline change also is meaningless, though, in the context of the non-comparability of the headline monthly data, which results from the BLS’s reporting methodology and use of concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors. Those issues are separate from recent official questions raised as to falsification of Current Population Survey results, from which the unemployment detail ultimately is derived.

On an unadjusted basis, the unemployment rates are not revised and at least are consistent in reporting methodology. July’s unadjusted U.3 unemployment rate rose to 5.55% (rounds to 5.6%), versus 5.46% in June.

The negligible change in the seasonally-adjusted, headline July U.3 unemployment rate reflected minimal changes in the number of unemployed individuals [down by 33,000 (-33,000)] and in the labor force [up by 69,000], differences that were meaningless in terms of statistical significance, and in terms of the regular non-comparability of the month-to-month, seasonally-adjusted headline numbers in this series.

Nonetheless, new discouraged and otherwise marginally-attached workers always are moving into U.6 unemployment accounting from U.3, while those who have been discouraged for one year continuously are dropped from the U.6 measure. As a result, the U.6 measure has been easing along with U.3, for a while, but those being pushed out of U.6 still are counted in the ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Estimate, which has remained stable.

U.6 Unemployment Rate. The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (i.e., they cannot find a full-time job).

With no change in the underlying seasonally-adjusted U.3 rate, a continuing decline in the adjusted number of people working part-time for economic reasons and a continuing increase in unadjusted discouraged workers and the balance of those marginally attached to the workforce, headline July 2015 U.6 unemployment eased to 10.39% from 10.52% in June. The unadjusted U.6 was at 10.75% (rounds to 10.7%) in July, versus 10.82% in June.

"Short-Term" Discouraged Workers. The count of short-term discouraged workers in July 2015 (never seasonally-adjusted) increased to 668,000, from 653,000 in June, versus 563,000 in May, 756,000 in April, and 738,000 in March. The latest, official discouraged-worker number reflected the flow of the unemployed—giving up looking for work—leaving the headline U.3 unemployment category and being rolled into the U.6 measure as short-term “discouraged workers,” net of the further increase in the number of those moving from short-term discouraged-worker status into the netherworld of long-term discouraged-worker status.

It is the long-term discouraged-worker category that defines the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure. There is a relatively heavy, continuing rollover from the short-term to the long-term category, with the ShadowStats measure encompassing U.6 and the short-term discouraged workers, plus the long-term discouraged workers. In 1994, “discouraged workers”—those who had given up looking for a job because there were no jobs to be had—were redefined so as to be counted only if they had been “discouraged” for less than a year. This time qualification defined away a large number of long-term discouraged workers. The remaining redefined short-term discouraged and redefined marginally-attached workers were included in U.6.

ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Estimate. Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the still-growing ranks of excluded, long-term discouraged workers—a broad unemployment measure more in line with common experience—the July 2015 ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate, eased to 23.0%, versus 23.1% in June. The ShadowStats estimate generally shows the toll of long-term unemployed leaving the headline labor force, as discussed in greater detail in the following section.

SHADOWSTATS-ALTERNATE UNEMPLOYMENT RATE MEASURE. In 1994, the BLS overhauled its system for estimating unemployment, including changing survey questions and unemployment definitions. In the new system, measurement of the previously-defined discouraged workers disappeared. These were individuals who had given up looking for work, because there was no work to be had. These people, who considered themselves unemployed, had been counted in the old survey, irrespective of how long they had not been looking for work.

The new survey questions and definitions had the effect of minimizing the impact on unemployment reporting for those workers about to be displaced by the just-implemented North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). At the time, I had close ties with an old-line consumer polling company, whose substantial economic monthly surveys were compared closely with census-survey details. The new surveying changed the numbers, and what had been the discouraged-worker category soon became undercounted or effectively eliminated. Change or reword a survey question, and change definitions, you can affect the results meaningfully.

The post-1994 survey techniques also fell far shy of adequately measuring the long-term displacement of workers tied to the economic collapse into 2008 and 2009, and from the lack of subsequent economic recovery. The BLS has a category for those not in the labor force who currently want a job. Net of the currently-defined "marginally attached workers," which includes the currently-defined discouraged-worker category used in the U.6, those not in the labor force currently wanting a job totaled 4.519 million in July 2015. While some may contend that number includes all those otherwise-uncounted discouraged workers, that number is far shy of underlying reality.

The ShadowStats number is my estimate. The approximation of the ShadowStats "long-term discouraged worker" category—those otherwise largely defined out of statistical existence in 1994—reflects proprietary modeling based on a variety of private and public surveying over the last two decades. Beyond using the BLS U.6 estimate as an underlying monthly base, I have not found a way of accounting fully for the current unemployment circumstance and common experience using just the monthly headline data from the BLS.

Some broad systemic labor measures from the BLS, though, are consistent in pattern with the ShadowStats measure, even allowing for shifts tied to an aging population. Shown in the Opening Comments, the graph of the inverted ShadowStats unemployment measure has a strong correlation with the employment-to-population ratio, in conjunction with the labor-force participation rate. Those series all are plotted subsequent to the 1994 overhaul of unemployment surveying.

Headline July 2015 Detail. Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the still-growing ranks of excluded, long-term discouraged workers—a broad unemployment measure more in line with common experience—the July 2015 ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate, eased to 23.0%, versus 23.1% in June. The July reading was down from the 23.3% series high in 2013 (back to 1994).

As seen in the usual graph of the various unemployment measures (Opening Comments), there continues to be a noticeable divergence in the ShadowStats series versus U.6 and U.3, with the headline BLS headline unemployment measures heading lower against a currently-stagnant, high-level ShadowStats number.

The reason for this is that U.6, again, only includes discouraged and marginally-attached workers who have been discouraged for less than a year. As the discouraged-worker status ages, those that go beyond one year fall off the government counting, even as new workers enter "discouraged" status. A similar pattern of U.3 unemployed becoming "discouraged" or otherwise marginally attached, and moving into the U.6 category, also accounts for the early divergence between the U.6 and U.3 categories.

With the continual rollover, the flow of headline workers continues into the short-term discouraged workers category (U.6), and from U.6 into long-term discouraged worker status (the ShadowStats measure). There was a lag in this happening as those having difficulty during the early months of the economic collapse, first moved into short-term discouraged status, and then, a year later they began moving increasingly into long–term discouraged status, hence the lack of earlier divergence between the series. The movement of the discouraged unemployed out of the headline labor force has been accelerating. While there is attrition in long-term discouraged numbers, there is no set cut off where the long-term discouraged workers cease to exist. See the Alternate Data tab for historical detail.

Generally, where the U.6 largely encompasses U.3, the ShadowStats measure encompasses U.6. To the extent that a decline in U.3 reflects unemployed moving into U.6, or a decline in U.6 reflects short-term discouraged workers moving into the ShadowStats number, the ShadowStats number continues to encompass all the unemployed, irrespective of the series from which they otherwise may have been ejected.

Great Depression Comparisons. As discussed in these regular Commentaries covering the monthly unemployment circumstance, an unemployment rate around 23% might raise questions in terms of a comparison with the purported peak unemployment in the Great Depression (1933) of 25%. Hard estimates of the ShadowStats series are difficult to generate on a regular monthly basis before 1994, given meaningful reporting inconsistencies created by the BLS when it revamped unemployment reporting at that time. Nonetheless, as best estimated, the current ShadowStats level likely is about as bad as the peak actual unemployment seen in the 1973-to-1975 recession and in the double-dip recession of the early-1980s.

The Great Depression unemployment rate of 25% was estimated well after the fact, with 27% of those employed working on farms. Today, less than 2% of the employed work on farms. Accordingly, a better measure for comparison with the ShadowStats number might be the Great Depression peak in the nonfarm unemployment rate in 1933 of roughly 34% to 35%.

__________

WEEK AHEAD

Economic Reporting Should Trend Much Weaker than Expected; Inflation Will Rise Anew, Along with Higher Oil Prices. In a fluctuating trend to the downside, amidst mixed reporting in headline data, market expectations for business activity nonetheless tend to respond to the latest economic hype in the popular media. The general effect holds the market outlook at overly-optimistic levels, with current expectations still exceeding any potential, underlying economic reality.

Headline reporting of the regular monthly economic numbers increasingly should turn lower in the weeks and months ahead, along with significant downside revisions to second-quarter 2015 GDP and downside or otherwise much weaker-than-expected reporting for at least the next several quarters of GDP into 2016.

CPI-U consumer inflation—driven lower earlier this year by collapsing prices for gasoline and other oil-price related commodities—likely has seen its near-term, year-to-year low, having turned positive in June 2015, for the first time in six months. July indicators still are signaling higher inflation in the next monthly reporting, with positive seasonal adjustments to gasoline prices. Separately, year-to-year CPI inflation for the balance of the year increasingly will be going against weak or negative year-ago numbers.

Upside inflation pressures should continue to build, as oil prices begin to rebound, once again, a process that should accelerate rapidly with the eventual sharp downturn in the exchange-rate value of the U.S. dollar. These areas, the general economic outlook and longer range reporting trends are reviewed broadly in No. 692 Special Commentary: 2015 - A World Out of Balance and will be updated soon in the August 10th Special Commentary and subsequent Hyperinflation Watch sections.

A Note on Reporting-Quality Issues and Systemic-Reporting Biases. Significant reporting-quality problems remain with most major economic series. Beyond the pre-announced gimmicked changes to reporting methodologies of the last several decades, which have tended to understate actual inflation and to overstate actual economic activity, ongoing headline reporting issues are tied largely to systemic distortions of monthly seasonal adjustments. Data instabilities—induced partially by the still-evolving economic turmoil of the last eight-to-ten years—have been without precedent in the post-World War II era of modern-economic reporting. The severity and ongoing nature of the downturn provide particularly unstable headline economic results, when concurrent seasonal adjustments are used (as with retail sales, durable goods orders, employment and unemployment data, discussed and explored in the labor-numbers related Commentary No. 695).

Combined with recent allegations of Census Bureau falsification of data in its monthly Current Population Survey (the source for the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Household Survey), these issues have thrown into question the statistical-significance of the headline month-to-month reporting for many popular economic series (see Commentary No. 669).

PENDING RELEASES:

Nominal Retail Sales (July 2015). The Census Bureau has scheduled release of July 2015 nominal (not-adjusted-for-inflation) retail sales for Thursday, August 13th, which will be reviewed in Commentary No. 743 of August 17th. Real (inflation-adjusted) retail sales for July will be published in ShadowStats Commentary No. 745 of August 19th, in conjunction with the detail on headline CPI-U reporting for July. Early expectations for July nominal sales are for a strong monthly rebound of 0.7% [MarketWatch], following the unexpected headline decline of 0.3% (-0.3%) in June sales. Headline July reporting should be much weaker than expectations.

With this series, in the current environment, downside-reporting surprises usually are a good bet, including a weaker-than-expected headline number for July and potential downside revisions to the May and June detail. With an outright contraction in headline nominal retail sales a possibility, real (inflation-adjusted) sales should be even more negative, given a likely monthly increase in the headline July CPI-U. Any unanticipated weakness in the July retail sales detail would be a good bet to dampen excessive growth expectations still surrounding broad economic activity and GDP reporting in the quarters ahead.

Constraining retail sales activity, the consumer remains in an extreme liquidity bind with weakening confidence, detailed most recently in the Opening Comments of prior Commentary No. 740, and as discussed in No. 692 Special Commentary: 2015 - A World Out of Balance. Without sustained growth in real income, and without the ability and/or willingness to take on meaningful new debt in order to make up for the income shortfall, the U.S. consumer is unable to sustain positive growth in domestic personal consumption, including retail sales, real or otherwise.

Index of Industrial Production (July 2015). On Friday, August 14th, the Federal Reserve Board will release its estimate of the index of industrial production for July 2015, which will be reviewed in Commentary No. 743 of August 17th. Early expectations for July production are for a headline month gain of 0.5%, following a 0.2% benchmark-revised gain in June [MarketWatch]. What will happen in headline July production reporting, however, has to be considered in the context of the meaningfully-negative annual benchmark revisions to the production series on July 21st (see Commentary No. 737).

Following the headline June production reporting of July 15th, the intervening revisions knocked the monthly, quarterly and annual growth patterns to the downside, and increasingly-negative data should lie ahead. As with the retail sales series, headline July reporting and monthly revisions to earlier months are likely to come in well below consensus, dampening overly-positive growth expectations surrounding broad economic activity and GDP reporting in the quarters ahead.

Producer Price Index—PPI (July 2015). The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) will release the July 2015 PPI on Friday, August 14th, which will be reviewed in Commentary No. 743 of August 17th. Odds favor a small headline monthly increase in wholesale inflation, although early expectations are for a minimal monthly contraction in wholesale inflation of 0.1% (-0.1%) [MarketWatch], following a headline PPI gain of 0.4% in June.

Unadjusted energy prices were flat-to-minus in July. Based on the two most-widely-followed oil contracts, not-seasonally-adjusted, monthly-average oil prices in July declined by 8.0% (-8.0%) and by 14.9% (-14.9%) for the month, with an accompanying decline of 0.2% (-0.2%) in unadjusted monthly-average retail-gasoline prices (Department of Energy). PPI seasonal adjustments for energy in July generally are neutral, although they are slightly positive for gasoline. Given the vagaries of margin shifts in the dominant services sector—where dropping oil prices often translate initially to increased margins and higher "inflation"—along with some likely added monthly inflation from wholesale food and "core" goods (everything but food and energy), the headline PPI change could be a small gain or decline. Likely headline reporting for this series, which often is volatile and irregular in its movement, is a toss-up this time around, but it is marginally more likely to be plus 0.1%, than minus 0.1% (-0.1%).

__________