No. 443: Employment and Unemployment, Construction, M3, PCE Deflator

COMMENTARY NUMBER 443

Employment and Unemployment, Construction, M3, PCE Deflator

June 1, 2012

__________

May Payrolls Up Just 20,000 versus Initial April Estimate

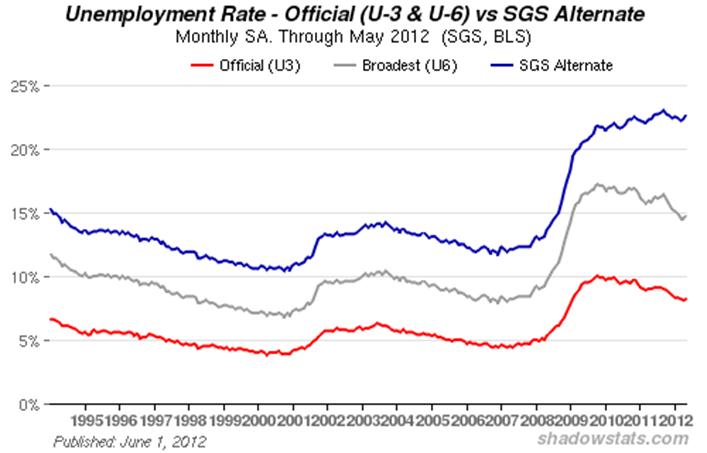

May Unemployment: 8.2% (U.3), 14.8% (U.6), 22.7% (SGS)

Annual M3 Money Supply Growth Slowed Further in May

Construction Spending Stagnation Continued in April

April PCE Deflator Dropped Below Fed’s Target

__________

CORRECTION: The table in the initial posting of yesterday’s Commentary, showing incumbent party loss of the White House versus growth in real disposable income, should have shown for 2008 “McCain Lost,” not “Bush Lost.” A corrected version of Commentary No. 442 has been posted on the Web site.

PLEASE NOTE: A Special Commentary is scheduled for Friday, June 8th. It will update the broad outlook for the U.S. economy, the U.S. dollar, Gold, systemic solvency and inflation/hyperinflation, as well as covering the April trade balance release.

Best wishes to all — John Williams

Opening Comments and Executive Summary. A pattern of slowing jobs growth has started to take hold in monthly payroll-employment reporting. While part of that likely reflects some catch-up from reporting earlier in the year that had been distorted to the upside, the trends here also are moving towards a softer economic reality, which is much more consistent with weak underlying fundamentals and a downtrending, bottom-bouncing economy, than it is with the “recovery” being shown in GDP reporting. Patterns of “unexpected” weakness could be expected to surface in other major May economic releases. In response, the consensus outlook should move anew towards a double-dip recession.

At the same time, annual growth in money supply M3 continues to slow, down to about 2.5% in May, from 3.1% in April (see Hyperinflation Watch). That likely reflects mounting systemic stress.

A full update on the outlook for economy and system-solvency will follow in the pending June 8th Special Commentary.

Employment and Unemployment. With 69,000 new jobs reported for May, and with downside revisions locking in slowing growth in recent months, the plot of the level of nonfarm payroll employment in the following graph has started to flatten out as of the most-recent reporting. The latest level remains well below the pre-2007 recession high and is not much above the pre-2001 recession high. There is no economic recovery evident here.

That said, the 69,000 jobs gain in May was not statistically significant and was just 20,000, net of the effects of prior-period revisions. The 0.1% upward notch in the May headline (U.3) unemployment rate to 8.2% from 8.1% in April also was not statistically significant. The lack of statistical significance means that within the recognized margins of reporting errors of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, nonfarm payrolls could have contracted, instead of increasing, and the unemployment rate could have notched lower, instead of rising.

Monthly increases were larger in broader unemployment measures that account for those having given up looking for work. The government’s U.6 measure, which includes an accounting for short-term discouraged and other marginally-attached workers, as well as for those working part-time for economic reasons (unable to find full-time employment), rose to 14.8% in May, from 14.5% in April. The SGS-Alternate Unemployment Measure, which includes U.6 and long-term discouraged workers, rose to 22.7% in May from 22.3% in April.

Construction Spending. April construction spending continued its pattern of low-level stagnation, even as viewed on a before-inflation-adjustment basis. The 0.3% monthly gain in April was not statistically significant and reflected a 1.2% increase in private construction that largely was offset by a 1.4% contraction in public construction.

PCE Deflator. Subject to a benchmark revision at the end of July, this heavily gimmicked inflation measure showed year-to-year inflation for April at 1.8%, below the Federal Reserve’s 2.0% inflation target, and April’s inflation pace was down from 2.1% in March.

The Fed’s “inflation targeting” effort primarily is pabulum for those in the markets who think the Fed really would move to contain inflation at the cost of impairing already-fragile banking-system solvency. The U.S. central bank’s primary function remains keeping the banking system afloat, at any cost. This should be evident at such time as the Fed introduces its next round of easing to help the banking system, under the guise of stimulating the economy.

Hyperinflation Watch. The outlook for the U.S. economy, U.S. dollar, systemic solvency and inflation (hyperinflation) has not changed from what was discussed in the January 25th Hyperinflation 2012, but conditions continue to evolve and regular review and updating are needed. Where reviews and updates are covered standardly in the regular Commentaries, the June 8th Special Commentary will provide a broad overview, supplanting Special Commentary No. 426 and Special Commentary No. 429, which previously updated the major economic and systemic-liquidity issues.

Money Supply M3 (May 2012). Based on roughly three weeks of reported data, the preliminary estimate of annual growth for the May 2012 SGS Ongoing-M3 Estimate—to be published tomorrow (June 2nd) in the Alternate Data section—is on track to slow to 2.5%, from a revised 3.1% (previously 3.0%) in April. With recent annual growth having peaked at 4.1% in January 2012, the upturn in annual growth that began in February 2011 has begun to reverse. Faltering broad money supply growth—in an environment of massive Federal Reserve accommodation—continues to be suggestive of an intensifying systemic-solvency crisis.

The seasonally-adjusted, month-to-month change estimated for May M3 likely will be around 0.2%, versus 0.1% in April. The estimated month-to-month M3 changes, however, remain less reliable than the estimates of annual growth.

For May 2012, early estimates of year-to-year and month-to-month change follow for the narrower M1 and M2 measures (M2 includes M1, M3 includes M2). M2 for May is on track to show year-to-year growth of about 9.5%, versus a revised 9.8% (previously 9.6%) in April, with month-to-month growth estimated at roughly 0.4%, the same as in April. The early estimate of M1 for May shows year-to-year growth of roughly 16.0%, versus an unrevised 18.1% in April, with month-to-month change a likely contraction of 0.4% in May, versus a gain of 1.2% in April. The relatively stronger annual growth rates in M1 and M2 continue to reflect an earlier shifting of funds out of M3 accounts into M1 and M2 accounts.

__________

REPORTING DETAIL

EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT (May 2012)

Payrolls Continued to Disappoint Market Expectations as Unemployment Rate Notched Higher. Underlying economic reality slowly is catching-up with the reporting of monthly labor conditions. Headline payroll employment disappointed consensus expectations for a third month, with the sharply slowing growth seen in April jobs also being in the context of downside revisions to payroll activity in March and April. The notching higher of headline unemployment U.3 reflected some likely catch-up from earlier seasonal-factor distortions that had depressed not only U.3, but also U.6. Where U.3 moved from 8.1% in April to 8.2% in May, the broader U.6 measure moved from 14.5% in April to 14.8% in May. These developments increasingly should move the consensus outlook towards weaker economic reporting in the near-term.

PAYROLL SURVEY DETAIL. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported today (June 1st) a statistically-insignificant, seasonally-adjusted May 2012 month-to-month payroll employment gain of 69,000 jobs (a gain of 20,000 before prior-period revisions) +/- 129,000 (95% confidence interval). The April payroll gain was revised to 77,000 (previously 115,000), while the March gain was revised to 143,000 (previously 154,000). In terms of year-to-year change, the unadjusted May 2012 annual growth was 1.39%, versus a revised 1.29% (previously 1.32%) in April, and versus an unrevised 1.55% in March.

As discussed in Payroll Trends, the trend indication from the BLS seasonal-adjustment model suggests a 113,000 payroll gain for June, based on today’s reporting. While the trend indication often misses actual reporting (the indication for May was 168,000), it usually becomes the basis for the consensus outlook.

The following graphs of year-to-year unadjusted payroll change had shown a slowly rising trend in annual growth into 2011, which primarily reflected the still-protracted bottom-bouncing in the payroll series. That pattern of growth flattened out in late-2011, as shown in the first graph of the near-term detail in year-to-year change, and it started to slow into April, with a bounce higher in May.

As shown in the longer-term graph (historical detail back to World War II), with the bottom-bouncing of recent years, current annual growth has recovered from the post-World War II record 5.06% decline in August 2009, which was the most severe annual contraction seen since the production shutdown at the end of World War II (a trough of a 7.59% annual contraction in September 1945). Disallowing the post-war shutdown as a normal business cycle, the August 2009 annual decline remains the worst since the Great Depression, yet the current level of employment is far from any recovery.

The regular graph of seasonally-adjusted payroll levels, which shows the current employment level well below its pre-2007 recession peak, is located in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary section.

Concurrent Seasonal Factor Distortions. Unreported, seasonally-adjusted monthly payroll numbers are showing an intensifying shift of first-half of the year jobs to the second-half of the year, as shown in the accompanying graph.

Despite revisions in the monthly data each month that go back years, the BLS only publishes two months of revisions with each release (March and April in the current instance), so as not to confuse data users. As a result, the reported March-through-May 2012 seasonally-adjusted payroll data are not consistent with earlier reporting. Conceivably, the shifting and unstable seasonal adjustments could move 70,000 jobs or more from earlier periods and insert them into the current period as new jobs, without there being any overt evidence of that happening.

The issues with the BLS’s concurrent seasonal factor adjustments and related inconsistencies in the monthly reporting of the historical time series are further discussed and detailed in the ShadowStats.com posting on May 2nd of Unpublished Payroll Data.

Incomplete and Inconsistent BLS Payroll Reporting. Four months have passed since the annual benchmark revisions to payroll employment, and the latest concurrent seasonal factors show renewed misreporting of the BLS’s own historical payroll levels, as well as ongoing instabilities in the BLS’s seasonal factors.

As discussed in prior writings (see Hyperinflation 2012, for example), seasonal-factor estimation for most economic series has been distorted severely by the extreme depth and duration of the economic contraction. These distortions are exacerbated for payroll employment data based on the BLS’s monthly seasonal-factor re-estimations and lack of full reporting.

Where the BLS recalculates the monthly seasonal factors each month for payroll employment, going back a number of years, outside of benchmarks, it only publishes the revised data for the last two months of reporting. The benchmark revision that accompanied the release of January 2012 payrolls, in theory, included a full update of the revised concurrent seasonally-adjusted data (actually it is off by a month or two). In the following graph, though, the latest revised (but not published by the BLS) adjusted payroll data show increasingly volatile, monthly seasonal-adjustment distortions of up to 70,000 jobs per month, with previously-reported payroll employment being shifted from the first-half to the second-half of the year. If seasonal-adjustment factors were stable in month-to-month reporting, which they should be, then the graph of differences would be flat and at zero.

Note: A further big issue remains that the month-to-month seasonally-adjusted payroll data have become increasingly worthless, with reporting errors likely now well beyond the official 95% confidence interval of +/- 129,000 jobs in the reported monthly payroll change. Yet the media and the markets tout the data as meaningful, usually without question or qualification.

Birth-Death/Bias Factor Adjustment. Despite the ongoing and regular overstatement of monthly payroll employment—as evidenced usually by regular and massive, annual downward benchmark revisions (2011 excepted)—the BLS generally adds in upside monthly biases to the payroll employment numbers. The process was created simply by adding in a monthly “bias factor,” so as to prevent the otherwise potential political embarrassment of the BLS understating monthly jobs growth. The “bias factor” process resulted from an actual such embarrassment, with the underestimation of jobs growth coming out of the 1983 recession. That process eventually was recast as the now infamous Birth-Death Model (BDM), which purportedly models the effects of new business creation versus existing business bankruptcies.

May 2012 Bias. The not-seasonally-adjusted May 2012 bias was a positive 204,000, versus a positive 206,000 in April, and versus a current estimation of a 211,000 upside bias in May 2011. The aggregate upside bias for the last 12 months was 518,000, versus 525,000 in April and 491,000 in March. At present that is a monthly average of 43,000 jobs created out of thin air, on top of some indeterminable amount of other jobs that are lost in the economy from business closings. Those losses simply are assumed away by the BLS as part of the BDM, as discussed below.

Problems with the Model. The aggregated upside annual reporting bias in the BDM reflects an ongoing assumption of a net positive jobs creation by new companies versus those going out business. Such becomes a self-fulfilling system, as the upside biases boost reporting for financial-market and political needs, with relatively good headline data, while often also setting up downside benchmark revisions for the next year, which traditionally are ignored by the media and the politicians. Where the BLS cannot measure the impact of jobs loss and jobs creation from employers starting up or going out of business, on a timely basis (within at least five years, if ever), such information is estimated by the addition of a bias-factor generated by the BDM.

Positive assumptions—commonly built into government statistical reporting and modeling—tend to result in overstated official estimates of general economic growth. Along with happy guesstimates, there usually are underlying assumptions of perpetual economic growth in most models. Accordingly, the functioning and relevance of those models become impaired during periods of economic downturn, and the current downturn has been the most severe—in depth as well as duration—since the Great Depression.

Indeed, historically, the BDM biases have tended to overstate payroll employment levels—to understate employment declines—during recessions. There is a faulty underlying premise here that jobs created by start-up companies in this downturn have more than offset jobs lost by companies going out of business. So, if a company fails to report its payrolls because it has gone out of business, the BLS assumes the firm still has its previously-reported employees and adjusts those numbers for the trend in the company’s industry.

Further, the presumed net additional “surplus” jobs created by start-up firms, get added on to the payroll estimates each month as a special add-factor. These add-factors are set now to add an average of about 43,000 jobs per month in the current year, but the actual overstatement of monthly jobs likely exceeds that number by a significant amount. With the underlying economy continuing to falter, I expect a significant downside benchmark revision for 2012 (based on the upcoming March 2012 benchmark that will be published in 2013), given current details of the BLS’s overly positive estimates.

HOUSEHOLD SURVEY DETAILS. The once statistically-sounder household survey, which counts the number of people with jobs, as opposed to the payroll survey that counts the number of jobs (including multiple job holders more than once) showed a monthly employment gain in May 2012 of 422,000, following a decline of 169,000 in April, and 31,000 decline in March. Yet, the headline unemployment rate rose, as the number of unemployed increased even faster, up 1.8% for the month, versus the 0.3% monthly gain in employment.

Note: Severe issues with monthly seasonal factors are ongoing and meaningfully cloud the significance of the reported monthly levels in the adjusted headline U.3 unemployment rate and other adjusted household-survey numbers

Unemployment Rates. The reported May 2012 seasonally-adjusted headline (U.3) unemployment rate rose by a statistically-insignificant 0.11 percentage point to 8.21% +/- 0.23%, versus April’s reported 8.10%. On an unadjusted basis, May’s U.3 unemployment rate was 7.9%, versus April’s 7.7%.

The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (they cannot find a full-time job).

The accounting for those working part-time due to economic reasons appeared to show some catch-up versus prior months’ data that had been skewed heavily by bad seasonal factors. The May U.6 unemployment rate rose to a seasonally-adjusted 14.8%, versus 14.5% in April. The unadjusted May U.6 rate rose to 14.3% from 14.1% in April.

Discouraged Workers. The count of short-term discouraged workers declined in May, as more unemployed moved into long-term discouraged worker status. The headline unemployed increasingly are giving up looking for work, leaving headline U.3 unemployment category and being rolled into the U.6 measure as short-term “discouraged workers.” Although the number of short-term discouraged workers fell in by 138,000 in May to 830,000 (the count never is seasonally adjusted), that is net of the number of discouraged workers who fell from the U.6 category into the long-term discouraged worker category that defines the SGS-Alternate Unemployment Measure.

In 1994, during the Clinton Administration, “discouraged workers”—those who had given up looking for a job because there were no jobs to be had—were redefined so as to be counted only if they had been “discouraged” for less than a year. This time qualification defined away the long-term discouraged workers. The remaining short-term discouraged workers (less than one year) are included in U.6.

Adding the SGS estimate of excluded long-term discouraged workers back into the total unemployed and labor force, unemployment—more in line with common experience as estimated by the SGS-Alternate Unemployment Measure—rose to 22.7%, from 22.3% in April. The SGS estimate generally is built on top of the official U.6 reporting, and tends to follow its relative monthly movements. Accordingly, the SGS measure will suffer some of the current seasonal-adjustment woes afflicting the base series, such as recent distortions in adjusted reporting of part-time employment for economic reasons. There still should be catch-up reporting in the months ahead (beyond today’s results), since the series do not use the concurrent-seasonal-factor methodology that is used with the payroll employment series.

Nonetheless, there continues to be a noticeable divergence in the SGS series versus U.6. The reason for this is that U.6, again, only includes discouraged workers who have been discouraged for less than a year. As the discouraged-worker status ages, those that go beyond one year fall off the government counting, and new workers enter “discouraged” status. Accordingly, with the continual rollover, the headline workers flow into the short-term discouraged workers counted in U.6 continue, and from U.6 into long-term discouraged worker status (SGS Measure) at what has been an accelerating pace. See the Alternate Data tab for more detail.

As discussed in previous writings, an unemployment rate above 22% might raise questions in terms of a comparison with the purported peak unemployment in the Great Depression (1933) of 25%. The SGS level likely is about as bad as the peak unemployment seen in the 1973 to 1975 recession. The Great Depression unemployment rate was estimated well after the fact, with 27% of those employed working on farms. Today, less that 2% work on farms. Accordingly, for purposes of Great Depression comparison, I would look at the estimated peak nonfarm unemployment rate in 1933 of 34% to 35%.

CONSTRUCTION SPENDING (April 2012)

Trend of Low-Level Stagnation Continued with April Construction Numbers. The latest construction activity remained heavily impaired, bouncing along at levels near current cycle lows. The Census Bureau reported today, June 1st, that the total value of construction put in place in the United States during April 2012 was $820.7 billion, on a seasonally-adjusted—but not inflation-adjusted—annual-rate basis. That estimate was up by a statistically-insignificant 0.3% (up by 1.6%, net of prior-period revisions) +/- 1.5% (all confidence intervals are at a 95% level) from an upwardly revised $818.1 billion (previously $808.1) in March. In turn, March showed a revised 0.3% (previously 0.1%) gain versus February.

Although construction was up by a statistically-significant 6.9% +/- 2.2% in April, the gain likely was more than covered by increases in construction costs. Year-to-year, March construction was up by a revised 7.3% (previously 6.0%).

The small aggregate gain in April construction spending reflected a continued decline in public spending, which was slightly more than offset by gains in the private sector. As reflected in the accompanying graphs, April private construction rose by 1.2% for the month, with residential construction up 2.8% and nonresidential construction down by 0.2%. April public construction continued in decline, down by 1.4% for the month.

The annual benchmark revision for the series is due for release along with the May report on July 2, 2012.

As shown in the preceding graph, in line with the ongoing bottom-bouncing reported through April 2012 in construction spending, and suggestive of that pattern having continued or deteriorated in May, seasonally-adjusted May construction employment turned to the downside. May construction jobs purportedly declined by 28,000 (down by 42,000 before prior-period revisions) for the month, to a level of 5.516 million, from a revised 5.544 (previously 5.558) million in April, per the May payroll survey.

PERSONAL CONSUMPTION EXPENDITURE (PCE) DEFLATOR (April 2012)

April PCE Deflator Virtually Flat for the Month; Year-to-Year Inflation at 1.8%. As reported today, June 1st, by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the month-to-month change in the seasonally-adjusted April 2012 PCE deflator virtually was unchanged for the month (up by 0.02%, by 0.1% net of prior-period revisions), against a revised 0.20% (previously 0.21%) monthly gain in March.

Year-to-year PCE deflator growth fell to 1.81% in April, breaking below the Fed’s 2.0% target. The annual gain was an unrevised 2.14% in March. Near- or below-target PCE inflation reporting, however, should not become a protracted pattern here, especially with the series facing an annual benchmark revision on July 31st.

Following in the gimmicked reporting of its quarterly GDP parent series, the monthly PCE deflator can vary widely month-to-month, thanks to prior-period revisions. Unlike the CPI-U series—which never is revised on a not-seasonally-adjusted basis so that the reported year-to-year inflation always remains fixed—the PCE deflator always is seasonally adjusted. The PCE deflator isn’t even estimated on an unadjusted basis.

In theory the PCE deflator measure should be virtually identical to the chain-weighted-CPI (C-CPI-U) (see Commentary No. 437 for details of the latest C-CPI-U and other inflation measures). The April 2012 PCE deflator showed 1.8% year-to-year inflation, versus 2.1% in March; such compared with annual inflation in the April C-CPI-U at 2.1%, versus 2.4% in March; April CPI-U at 2.3%, versus 2.7% in March; April CPI-W at 2.4%, versus 2.9% in March; and the April SGS-Alternate (1980-Base) at 9.9%, versus 10.3% in March. Reported annual PCE-deflator inflation is shown in the following graphs against the C-CPI-U and the CPI-U

As noted in Commentary No. 442, the first-quarter 2012 PCE deflator rose at a revised annualized pace of 2.40% (previously 2.39%), up by an unrevised 2.30% year-to-year and above the Fed’s 2.0% target. The fourth-quarter PCE deflator rose at an annualized pace of 1.17%, up by 2.67% year-to-year.

This “inflation targeting” effort by the Federal Reserve primarily is window-dressing for those in the markets who think the Fed really would move to contain inflation at the cost of impairing already-fragile banking-system solvency. The Fed’s primary function remains keeping the banking system afloat, at any cost.

NOTE: The PCE deflator is the heavily massaged and modeled inflation rate for personal consumption expenditure, published on a monthly basis by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), and quarterly as part of the GDP release. The monthly series, which is a surrogate measure of consumer inflation—fully substitution and hedonic-based—currently is yielding the lowest annual consumer inflation rate of the major series (see the preceding graphs of the PCE deflator versus the CPI-U and the C-CPI-U. Unlike the more widely followed CPI-U measure, which never is revised and is published on a seasonally unadjusted-basis, the PCE deflator is heavily revised for many years following initial reporting, and it is available only on a heavily-massaged, seasonally-adjusted basis.

Week Ahead. Recognition of an intensifying double-dip recession as well as an escalating inflation problem remains sporadic. The political system would like to see the issues disappear until after the election; the media does its best to avoid publicizing unhappy economic news; and the financial markets will do their best to avoid recognition of the problems for as long as possible, problems that have horrendous implications for the markets and for systemic stability.

Until such time as financial-market expectations move to catch up fully with underlying reality, or underlying reality catches up with the markets, reporting generally will continue to show higher-than-expected inflation and weaker-than-expected economic results in the months and year ahead. Increasingly, previously unreported economic weakness should show up in prior-period revisions.

Trade Balance (April 2012). Due for release on Friday, June 8th, by the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the April trade deficit likely will be wider than consensus estimates. The new numbers will be published along with, and in the context of, an annual benchmark revision to the series back to January 2009.

__________