No. 686: December Employment and Unemployment, Money Supply M3

COMMENTARY NUMBER 686

December Employment and Unemployment, Money Supply M3

January 9, 2015

__________

Revisions to Unemployment Seasonal-Adjustments

Demonstrated Concurrent-Seasonal-Factor Reporting Issues

Payroll and Unemployment Data Both Heavily Skewed by

Unstable and Inconsistent Seasonal Adjustments

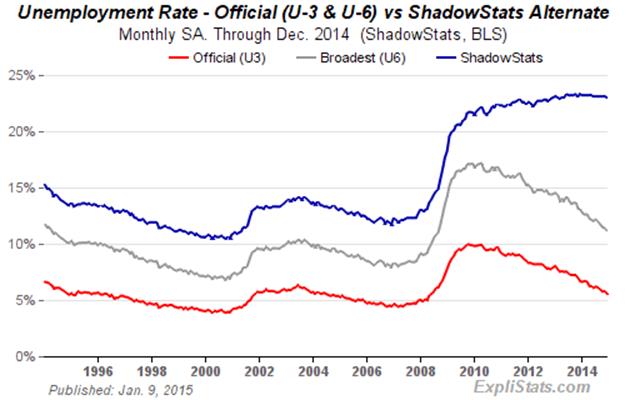

December Unemployment Rates: 5.6% (U.3), 11.2% (U.6), 23.0% (ShadowStats)

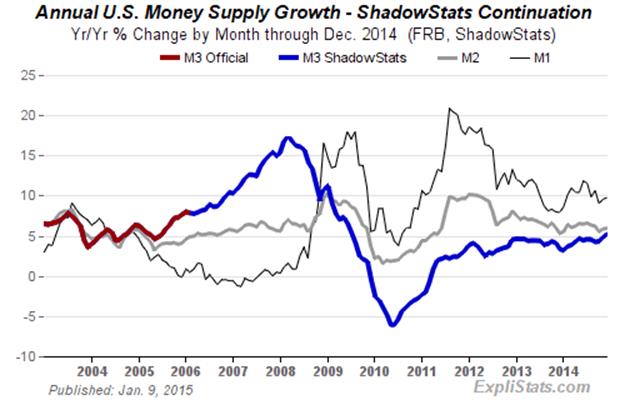

Annual Money Supply M3 Growth Jumped to 5.2% in December, Highest Since July 2009

___________

PLEASE NOTE: The Special Commentary will be the next Commentary published, following as soon as possible. Details will be advised in the schedule box in the upper left-column of the home page. The next Regular Commentary is scheduled for Wednesday, January 14th, covering December retail sales, followed by one on Friday, December 16th, covering the December CPI, PPI and industrial production.

Best Wishes to all — John Williams

OPENING COMMENTS AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

No Determining if Headline Employment and/or Unemployment Is Rising or Falling with Any Degree of Certainty. This morning, January 9th, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published its annual five-year benchmark revision just to seasonal factors, involving items in the household survey such as monthly counts on employment, unemployment, people working part-time for economic reasons, along with the unemployment rates U.3 and U.6. The unadjusted data never are revised, so the revisions here reflected only month-to-month shifts in seasonal adjustments that would tend to be stable in normal times. Times are not normal, and the adjustments are not stable. The publication of the revisions here was coincident with the headline reporting of December 2014 employment and unemployment.

ShadowStats long has contended that the use of concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors has left the headline monthly changes in the household data not meaningful, simply because the resulting month-to-month data are not comparable. That was confirmed to a certain extent with today’s revisions. Comparable month-to-month numbers are in place, the only time during the year , with the December seasonal-adjustment revision. They numbers become not comparable, again, with January reporting.

The reporting inconsistencies do not arise from the concurrent-seasonal-adjustment process itself, but from the BLS’s refusal to publish restated, consistent historical data, which are recalculated each month. By establishing a unique a set of seasonal factors for each new headline monthly reporting, the BLS recalculates seasonal-adjustments for the entire series, going back five years.

That means whatever was reported the last month no longer is calculated on the same basis with, nor is it comparable to, the current month. While in aggregate the revised seasonal factors did not change the broad patterns of reporting, they certainly changed headline monthly reporting that could have had an impact on the financial markets.

For example, consistent with today’s headline reporting of December 2014 seasonally-adjusted unemployment of 5.6%, November was reported at an unrevised 5.8%, but October was revised to 5.7% (previously 5.8%). So based on consistent reporting with December, the headline U.3 unemployment rate rose by 0.1% in November, instead of being unchanged, as reported with November headline numbers. Would that have had market impact? Month-to-month revisions of +/- 0.1% in the headline unemployment-rate change were common. Again, whatever the actual October-to-November change was, or whatever the earlier rates really were, such was based on headline reporting of the time, not on today’s headline December 2014 reporting. What the actual headline unemployment rates were on a monthly basis, over the last five years, is not knowable at present by the public.

Looking at revisions for the last five years, which again reflect only the monthly shifts in seasonal adjustment patterns between last revision of December 2013 reporting and today’s December 2014 report, and ignoring January levels affected by population re-estimation each year, month-to-month change in headline reporting often revised by plus or minus more than 100,000 people (employment, unemployed count, part-time employment for economic reasons, etc.). With such patterns of revision, one should not have too much confidence in the significance of the regular headline household-survey data.

Separately, the Headline Jump of 252,000 in December Payrolls Was Skewed Heavily by Poor-Quality and Inconsistent Seasonal Adjustments. Headline December 2014 payrolls surged, again, on top of upside revisions to seasonally-adjusted, prior-period revisions. As increasingly has become the common circumstance, the upside revisions in headline monthly numbers simply are constructs of highly unstable, inconsistent and questionable seasonal adjustments being shifted between months. The unadjusted data do not revise, but the adjusted data pick up bogus growth from gimmicked reporting, as discussed further in the Reporting Detail section.

Today’s Missive (January 9th). Today’s Commentary concentrates on detail from the reporting of the December 2014 labor data and the initial estimate of December money supply M3.

The Week Ahead section highlights pending reporting of the December retail sales, industrial production and the CPI and PPI inflation numbers.

Given the extensive new material in the still-pending publication of the year-end Special Commentary, today’s missive excludes any general review of economic activity, other than for the employment and unemployment detail. Similarly, the Hyperinflation Watch section excludes its usual Summary content, but it does cover the initial estimate of December 2014 M3 growth.

Employment and Unemployment—December 2014—Nonsense Numbers Continued. With today’s annual benchmark revision to the seasonally-adjusted household-survey data, and next month’s annual benchmark revision to payroll-survey data, the significance of monthly headline employment and unemployment reporting increasingly should be called into question. Also, in the Reporting Detail section, check out the link to John Crudele’s recent article in the New York Post, as to the potential for further Congressional investigation of data falsification at the Bureau of the Census.

Headline December 2014 Payroll Employment. The seasonally-adjusted, month-to-month headline payroll-employment gain for December 2014 was 252,000, somewhat above market expectations and well above trend. The December gain followed a revised 353,000 (previously 321,000) gain in November, and a revised, fraudulent 261,000 (previously 243,000, initially 214,000) gain in October.

In a pattern that has been repeated regularly in recent months, the upside revisions to October and November primarily were due to irregular shifts in the seasonal-factor adjustments used to help boost the current month’s (December 2014) headline data. The revised gains were not due to updated, better-quality unadjusted raw data. Instead, as commonly repeated, the unadjusted payroll levels in both October and November had negligible revisions, while the adjusted data revised sharply higher.

Fraudulent Monthly Gains. The use by the BLS of concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors in payroll employment reporting also restates seasonally-adjusted, historical monthly payroll levels each-and-every month, and that results in effective monthly reporting fraud by the BLS, where BLS publishes headline detail it knows to be wrong. Where the new headline number is created in its own unique seasonally-adjusted environment, the reporting fraud, again, comes not from the adjustment process, itself, but rather from the BLS not publishing the newly revised history each month; by the BLS not allowing for honest comparisons of the adjusted monthly numbers.

In December’s headline reporting, for example, only the headline monthly changes for December and November 2014 were comparable with each other. Due to unreported historical revisions to September 2014 data from the seasonal-adjustment process that generated the headline December number, the headline October change from September was a gain of 256,000, based on consistent and comparable reporting, instead of the purported headline 261,000 increase shown in the BLS’s press release.

In like manner, the current headline gain of 271,000 jobs in September really is 256,000 on a basis consistent with December’s headline reporting, and the headline gain for August of 203,000 really is 190,000. All these numbers will be recast again next month with the annual benchmark revision to the payroll survey. Unlike the unemployment numbers, which are brought into consistent reporting, once per year, along with the December revision to seasonal adjustments, that never happens with the payroll series. The reason being is that the annual-benchmark revision to payrolls and modeling is run covertly for testing purposes for two months, before the next headline detail becomes available, so the published headline data never have a chance to catch up on a consistent or comparable basis.

Encompassing benchmarking, Birth-Death Model biases and distortions from the concurrent-seasonal- adjustment process, the 95% confidence interval around the headline monthly change in payrolls more appropriately should be in excess of +/- 300,000, instead of the official +/- 129,000.

Annual Change in Payrolls—Steady Despite Headline Monthly Surge. Despite the nonsensical surges in recent headline payroll activity, year-to-year growth has held reasonably steady, albeit still at a post-recession high level. Not-seasonally-adjusted, year-to-year change in payroll employment is untouched by the concurrent-seasonal-adjustment issues, so the monthly comparisons of year-to-year change are reported on a consistent basis, although the redefinition of the series—not the standard benchmarking process—recently boosted reported annual growth in the last year, as discussed and graphed in the benchmark detail of Commentary No. 598 and as graphed in Reporting Detail.

For December 2014, year-to-year or annual nonfarm payroll growth was 2.16%, up from a revised 2.01% (previously 2.00%) in November, and a revised 2.02% (initially 2.03%) in October. Had the 2013 benchmark revision been standard, not a gimmicked redefinition (see short-term payroll graph in the Reporting Detail), year-to-year jobs growth as of December 2014 would have been about 1.8%, consistent with an otherwise near-term peak annual growth of about 1.9% in February 2012.

Counting All Discouraged Workers, December 2014 Unemployment Was 23.0%. The headline household survey reporting remains virtually worthless on a month-to-month basis. Previously discussed, aside from sampling–quality issues, the numbers are highly volatile and unstable, inadequately defined—not reflecting common experience—and simply are not comparable on a month-to-month basis, except for the December reporting, which, with its seasonal adjust revisions, brings the last five years of household reporting into a comparable and consistent form, for one month.

The usual month-to-month comparability issue results from the concurrent seasonal adjustment process, are discussed above and in the Reporting Detail section. Beginning again with January 2015 data, the BLS will revise all historical data each month, in setting the headline month’s seasonal factors, but it will not publish the new, revised and comparable historical data. Instead, the BLS likely will leave the old, non-comparable data, in place, without comment, as it has done for years.

For the only time since December 2013, and for the only time before December 2015, the December 2014 and prior monthly household survey detail are revised on a one-time only basis so to be consistent. Accordingly, all the household survey data referenced or plotted in today’s Commentary have been fully revised, although, in broad scope, the new detail is not that noticeably different from the old detail.

More than anything else, though, what removes headline-unemployment reporting from broad underlying economic reality and common experience simply is definitional. To be counted among the headline unemployed (U.3), an individual has to have looked for work actively within the four weeks prior to the unemployment survey. If the active search for work was in the last year, but not in the last four weeks, the individual is considered a "discouraged worker" by the BLS. ShadowStats defines that group as "short-term discouraged workers," as opposed to those who become "long-term discouraged workers" after one year.

Moving on top of U.3, the broader U.6 unemployment measure includes only the short-term discouraged workers. The still-broader ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure includes an estimate of all discouraged workers, including those discouraged for one year or more, as the BLS used to measure the series pre-1994, and as Statistics Canada still does.

When the headline unemployed become "discouraged," they are rolled over from U.3 to U.6. As the headline, short-term discouraged workers roll over into long-term discouraged status, they move into the ShadowStats measure, where they remain. Aside from attrition, they are not defined out of existence for political convenience, hence the longer-term divergence between the various unemployment rates. Further detail is discussed in the Reporting Detail section. The resulting difference here is between a headline December 2014 unemployment rates of 5.6% (U.3) and 23.0% (ShadowStats).

The graph immediately preceding reflects headline December 2014 U.3 unemployment at 5.6%, down from 5.8% in November; headline December U.6 unemployment at 11.2%, down from 11.4% in November; and the headline December ShadowStats unemployment measure holding at 23.0%, down from a revised 23.1% (previously 23.0%) in November. The ShadowStats revised series high (since 1994) was seen in June, October and December 2013 at 23.3%. Previously the ShadowStats high had been at 23.4% in October 2013. The ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure series is built upon the BLS reporting of seasonally-adjusted U.3 and U.6 series, and correspondingly, it is affected by annual seasonal adjustments to those series.

The three graphs that follow reflect longer-term unemployment and discouraged-worker conditions. The first graph is of the ShadowStats unemployment measure, with an inverted scale. The higher the unemployment rate, the weaker will be the economy, so the inverted plot tends to move in tandem with plots of most economic statistics, where a lower number means a weaker economy.

The inverted-scale of the ShadowStats unemployment measure also tends to move with the employment-to-population ratio, which is plotted in the second graph. Discouraged workers are not counted in the headline labor force, which generally continues to shrink. The labor force containing all unemployed (including total discouraged workers) plus the employed, however, tends to be correlated with the population, so the employment-to-population ratio tends to be something of a surrogate indicator of broad unemployment, and it has a strong correlation with the ShadowStats unemployment measure.

The third graph is a new one, a plot of the labor-force participation rate (headline labor force as a percent of population), a series frequently touted by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen. The labor force here is the headline employment plus U.3 unemployment. So, as with the prior graph of employment to population, its moving to a record low in the current reporting is another indication of problems with long-term discouraged workers, the loss of whom continues to shrink the headline (U.3) labor force, and the plotted ratio.

These three graphs reflect detail back to the 1994 redefinitions of the household survey. Before 1994, data consistent with December’s reporting simply are not available.

Headline Unemployment Rates—December 2014. In the context of the annual benchmark revision to related seasonal adjustments, the headline December 2014 unemployment (U.3) rate decreased by 0.24-percentage point to 5.56% from a revised 5.80% (previously 5.82%) in November. On an unadjusted basis, the unemployment rates never are revised and at least are consistent each month in reporting methodology. December’s unadjusted U.3 unemployment rate was 5.4%, down from 5.5% in November.

With a small, seasonally-adjusted decline in people working part-time for economic reasons and a more-than-offsetting increase in discouraged workers and those marginally attached to the workforce (unadjusted), headline December 2014 U.6 unemployment declined to 11.20%, from a revised 11.38% (previously 11.40%) in November. The unadjusted U.6 increased to 11.1% in December, from 11.0% in November.

Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the growing ranks of excluded, long-term discouraged workers—more in line with common experience—broad unemployment, the December 2014 ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure, eased to 23.0%, down from a revised 23.1% (previously 23.0%) in November. That was down from a revised 23.3% (previously 23.4%) series high in 2013 (back to 1994). The ShadowStats estimate generally shows the toll of long-term unemployed leaving the headline labor force. It also tends to revise with U.3 and U.6 benchmarks.

[Further detail on the Employment and Unemployment Data, are found in the Reporting Detail. Various drill-down and graphics options on the headline Labor data also are available to subscribers at our affiliate: www.ExpliStats.com].

__________

HYPERINFLATION WATCH

Recent Monetary Conditions—M3 Growth at Five-Year High. The Federal Reserve Board has ceased net new purchases of U.S. Treasury securities as part of its quantitative easing QE3, but its holdings of Treasury securities have been stable. Despite high-level volatility in the monetary base during the last month, annual growth in December 2014 money supply M3 increased, tentatively, to 5.2%, the strongest showing in five years, since July of 2009. These circumstances are discussed further in the forthcoming Special Commentary.

Money Supply M3 Annual Growth Tentatively Rose to 5.2% in December. Year-to-year change in December 2014 M3 (ShadowStats Ongoing Measure) jumped to 5.2%, from a revised 4.8% (previously 4.7% in November. Prior-period revisions were due to regular and frequent revisions of the underlying detail provided by the Federal Reserve.

Monthly year-to-year growth began to slow, after hitting a near-term peak of 4.6% in each of the months of January, February and March 2013, the onset of expanded QE3. Growth then fell to a near-term trough of 3.2% in January 2014, but that period of slowing growth had reversed fully as of May 2014, with annual growth recovering 4.6%. Annual growth pulled back to a revised 4.4% in June 2014, but rose again to 4.6% in July, easing back to 4.5% in August. Growth slowed further to 4.3% in September and October, and then jumped to 4.8% and 5.2%, respectively, in November and December.

Formal M3 estimates and the first readings of annual growth for M2 and M1 in December 2014 have been updated on the Alternate Data tab of www.ShadowStats.com.

The seasonally-adjusted, preliminary estimate of month-to-month change for December 2014 money supply M3 was roughly a gain of 0.6%, versus an unrevised 0.7% in November. Estimated month-to-month M3 changes, however, remain less reliable than are the estimates of annual growth.

Growth for December M1 and M2. For December 2014, year-to-year and month-to-month changes follow for the narrower M1 and M2 measures (M2 includes M1; M3 includes M2). See the Money Supply Special Report for full definitions of those measures. Annual M2 growth in December 2014 rose to roughly 6.0%, from an unrevised 5.9% in November, with a month-to-month gain of about 0.6% in December, versus an unrevised 0.4% gain in in November. For M1 in December 2014, year-to-year growth rose to about 9.8%, versus a revised 9.6% (previously 9.5%) in November, with a month-to-month December gain of 1.7%, versus a revised 0.1% (-0.1%) contraction in November, which previously had shown a monthly contraction of 0.2% (-0.2%).

__________

REPORTING DETAIL

EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT (December 2014)

Ongoing, Seriously-Flawed Headline December Reporting of Jobs Growth and Unemployment. Incorporated here by reference are today’s Opening Comments, which discuss reporting irregularities in the headline December labor data and the benchmark revision to seasonally-adjusted household-survey data.

Both the December 2014 headline jobs growth of 252,000 and the headline 0.2% decline in the unemployment rate to 5.6% remained far removed from common experience and underlying reality. Quality issues continue to reflect extreme seasonal-factor distortions and the general lack of month-to-month data comparability. Discussed frequently in these Commentaries, common experience generally would suggest flat headline monthly payroll employment, plus or minus in December, with a broad unemployment rate—encompassing all short- and long-term discouraged workers—running around 23%.

Common for most of 2014, headline employment gains have been no more than statistical illusions resulting from hidden shifts in seasonal factors, and from phantom-jobs creation with the benchmark revision to March 2013 payrolls (published in January 2014), combined with the Birth-Death Model’s upside bias factors (see the Birth-Death/Bias-Factor Adjustment and Concurrent Seasonal Factor Distortions sections for extended detail).

In December’s reporting, current and long-term U.3 underreporting of unemployment, versus common experience, reflects the BLS removal of discouraged workers from the counts of the unemployed and the labor force (see ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Rate). Separately, month-to-month comparisons of these numbers have little meaning; they simply are not comparable thanks to the concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustment process as practiced by the BLS. The exception is for one-time annual revisions, as seen in the December 2014 headline reporting and household survey revisions (see the Opening Comments and Concurrent Seasonal Adjustment Distortions sections).

Recently, an issue also has arisen as to the falsification of the household survey by employees of the Census Bureau, who conduct the underlying Current Population Survey. Details on the related Congressional investigation were discussed in Commentary No. 669. See the HOUSEHOLD SURVEY section for a request and link to new comments from John Crudele of the New York Post, who broke the story that triggered Congressional action.

PAYROLL SURVEY DETAIL. Published January 9th, by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the seasonally-adjusted, month-to-month headline payroll-employment gain for December 2014 was 252,000 jobs +/- 129,000 (95% confidence interval) somewhat above market expectations and well above trend.

The December gain followed a revised 353,000 (previously 321,000) gain in November, and a revised, fraudulent 261,000 (previously 243,000, initially 214,000) gain in October.

In a regularly-repeating pattern, and as discussed again in the Opening Comments, the upside revisions to October and November were due to irregular shifts in seasonal-factor adjustments used to help boost the December headline data. The revised gains were not due to updated, better-quality unadjusted raw data. Again, as usual, the unadjusted payroll levels in both October and November had negligible revisions, while the adjusted data revised sharply higher.

Fraudulent Monthly Gains. Frequently discussed here are the implications of the BLS’s use of concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors, which restates seasonally-adjusted historical monthly payroll levels each-and-every month, as the new headline number is created in its own, unique seasonally-adjusted environment. The reporting fraud comes not from the adjustment process, itself, but rather from the BLS not publishing the newly revised history each month, and by not allowing for honest comparisons of the numbers.

In December’s headline reporting, for example, only headline monthly changes for December and November 2014 were comparable with each other. Due to unreported historical revisions to September 2014 data from the seasonal-adjustment process generating the headline December number, the headline October change from September was a gain of 256,000, based on consistent and comparable reporting, instead of the purported headline 261,000 increase shown in the BLS’s press release.

In like manner the current headline gain of 271,000 jobs in September really is 256,000 on a basis consistent with December’s headline reporting, and the headline gain for August of 203,000 really is 190,000. All these numbers will be recast in the annual benchmark revision to the payroll survey.

Where the current employment levels have been spiked by misleading and inconsistently-reported concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustments, the reporting issues suggest that a 95% confidence interval around the monthly headline payroll gain should be well beyond +/- 200,000 around the formal modeling of the headline gain, instead of the official +/- 129,000. Even if the data were reported on a comparable month-to-month basis, other reporting issues would prevent the indicated headline magnitudes of change from being significant. Encompassing Birth-Death Model biases, the confidence interval more appropriately should be in excess of +/- 300,000.

“Trend Model” Estimate Subject to Vagaries of Upcoming Payroll Benchmarking. As discussed in Commentary No. 679, and as described generally in Payroll Trends, the trend indication from the BLS’s concurrent-seasonal-adjustment model—prepared by our affiliate www.ExpliStats.com—was for a December 2014 monthly payroll gain of 214,000, based on the BLS trend model structured into November’s actual reporting. The late-consensus for December 2014 reporting was 245,000 (Bloomberg), where the headline gain came in at 252,000, slightly above consensus well above trend. Full detail on the headline payroll data, including various drill-down and graphics options are available to ShadowStats subscribers at ShadowStats-affiliate www.ExpliStats.com.

January 2015 Trend Estimate. Based on the December 2014 BLS seasonal-adjustment modeling, the trend number calculations suggest a headline gain of 245,000 for January 2015. While the consensus outlook for January reporting most likely will settle-in around that number, the actual trend number likely will have been revised, and not otherwise available, based on the restructuring of the historical data for the benchmark revision, pending with the release of January data on February 6th.

Construction Payrolls. Updating the graph of construction payrolls shown in Commentary No. 685, and in the context of fraudulent revision patterns (upside revisions to seasonally-adjusted data, versus negligible changes the hard, unadjusted numbers), parallel to the issues with the headline aggregate reporting, headline December 2014 construction rose by 48,000 for the month (up by 57,000, net of prior-period revisions). The strength in the headline construction jobs generally ran counter to all other indications of flat-to-down construction activity.

The December gain of 48,000 was against an unrevised 20,000 gain in November (upside-adjusted revisions were in October), and a revised 16,000 (previously a 7,000, initially a 12,000) gain in October.

The construction payroll numbers are heavily biased to the upside (officially bloated by 5,000 jobs per month, unofficially at an order of magnitude of 20,000 jobs per month). Nonetheless, total December 2014 construction jobs still were down by 20.2% (-20.2%) from the pre-recession peak for the series in April 2006.

Annual Change in Payrolls—Steady Despite Headline Monthly Surge. Despite the nonsensical surges in recent headline payroll activity, year-to-year growth has held reasonably steady, albeit still at a post-recession high level. Not-seasonally-adjusted, year-to-year change in payroll employment is untouched by the concurrent-seasonal-adjustment issues, so the monthly comparisons of year-to-year change are reported on a consistent basis, although the redefinition of the series—not the standard benchmarking process—recently boosted reported annual growth in the last year, as discussed and graphed in the benchmark detail of Commentary No. 598.

For December 2014, year-to-year or annual nonfarm payroll growth was 2.16%, up from a revised 2.01% (previously 2.00%) in November, and a revised 2.02% (initially 2.03%) in October. Had the 2013 benchmark revision been standard, not a gimmicked redefinition (see short-term payroll graph, first graph following), year-to-year jobs growth as of December 2014 would have been about 1.8%, consistent with an otherwise near-term peak annual growth of about 1.9% in February 2012.

With bottom-bouncing patterns of recent years, current headline annual growth has recovered from the post-World War II record 5.02% (-5.02%) decline seen in August 2009, as shown in the accompanying graphs. That 5.02% (-5.02%) decline remains the most severe annual contraction since the production shutdown at the end of World War II [a trough of a 7.59% (-7.59%) annual contraction in September 1945]. Disallowing the post-war shutdown as a normal business cycle, the August 2009 annual decline was the worst since the Great Depression.

Historical Payroll Levels and the Employed. Putting aside the various reporting-quality issues with both the nonfarm payroll series and the household survey’s employment series, consider that the household survey estimates the number of people who are employed in the civilian population (including agriculture, excluding military), irrespective of the number jobs they may hold.

The payroll survey estimates the number of jobs in the economy (excluding agriculture and military), irrespective of how many total people actually work at those jobs. Multiple-jobs holders in the payroll survey often have at least one part-time job. Those who have only one job, which is part-time, or who hold multiple part-time jobs, often would prefer full-time employment but have been unable to find it. Separate accounting, though, of full-time and part-time employment is found only in the household survey, and the details largely are irreconcilable with the payroll-survey data.

That said, employment is a coincident indicator of economic activity, and both the payroll and employment series formally regained their pre-recession highs in 2014, despite the GDP purportedly having done the same back in 2011. Reflected in the following graphs, headline payroll employment moved to above its pre-recession high in May 2014, and it has continued to rise, although the number of employed individuals did not reach that milestone until September 2014.

The first two graphs reflect the payroll series, both on shorter-term basis since 2000, and on a longer-term historical basis from 1940. Addressed in the short-term graph, the pattern of recovery in the payroll level count was redefined favorably with the January 2014 benchmark revision of March 2013 payrolls, despite the actual benchmark having been negative. The yellow points in that graph reflect the ShadowStats assessment of what payroll employment would be showing with just a regular benchmarking, instead of the gimmicked redefinition of the series, which added a new upside bias. Even with what should have been a standard benchmarking, though, the pre-recession level was broken with the September 2014 reporting.

In perspective, the longer-term graph of the headline payroll-employment levels shows the extreme duration of what had been the official non-recovery in payrolls, the worst such circumstance of the post-Great Depression era.

Shown in the next two graphs of aggregate (including part-time) and full-time household employment, where the aggregate series indeed recovered its pre-recession peak in 2014, the number of full-time unemployed did not. Those with full-time employment still are about 1.9 million shy of the pre-recession peak, based on December’s headline reporting. The difference with the payroll series has been made up by a surge in part-time employment during the still-ongoing recession, where the bulk of that gain has reflected those working part-time for economic reasons, unable to find a full-time job.

Concurrent-Seasonal-Factor Distortions. There are serious and deliberate reporting flaws with the government’s seasonally-adjusted, monthly reporting of both employment and unemployment. Each month, the BLS uses a concurrent-seasonal-adjustment process to adjust both the payroll and unemployment data for the latest seasonal patterns. As each series is calculated, the adjustment process also revises the monthly history of each series, recalculating prior seasonally-adjusted reporting for every month, going back five years, on a basis that is consistent with the new seasonal patterns of the headline number.

The BLS, uses and publishes the current headline estimate, but it does not publish the revised history, even though it calculates the consistent new data each month. As a result, headline reporting generally is neither consistent with, nor comparable to earlier reporting, and month-to-month comparisons of these popular numbers usually are of no substance, other than for market hyping or political propaganda.

The BLS explains that it avoids publishing consistent, prior-period revisions so as not to "confuse" its data users. No one seems to mind if the published earlier numbers are wrong, particularly if unstable seasonal-adjustment patterns have shifted prior jobs growth or reduced unemployment into current reporting, without any formal indication of the shift from the previously-published historical data.

The accompanying graph shows how far the monthly payroll employment data have strayed from being consistent, as of the latest December 2014 reporting, versus the 2013 benchmark revision to the series in February 2014. The February 6th reporting of the January 2015 payroll data will reflect the new, 2014 benchmark revision and a recasting of the accompanying graph. If the reporting were comparable and stable month-after-month, all the lines in the graph would be flat and at zero. With the payroll series, only the headline month and the prior month are consistent in terms of month-to-month reporting detail, prior data (October 2014 and before, per the latest headline reporting) are not comparable.

In terms of the household survey, none of the month-to-month reporting is consistent, except in the once-per-year reporting of December data, when the annual revisions to seasonal adjustments are published. This year’s revision, published with today’s release, is discussed in the Opening Comments. Come next month’s reporting, all month-to-month data will be not comparable, once again.

Note: Issues with the BLS’s concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustments and related inconsistencies in the monthly reporting of the historical time series are discussed and detailed further in the ShadowStats.com posting on May 2, 2012 of Unpublished Payroll Data.

Birth-Death/Bias-Factor Adjustment. Despite the ongoing, general overstatement of monthly payroll employment, the BLS adds in upside monthly biases to the payroll employment numbers. The continual overstatement is evidenced usually by regular and massive, annual downward benchmark revisions (2011 and 2012, excepted). As discussed in the benchmark detail of Commentary No. 598, the regular benchmark revision to March 2013 payroll employment was to the downside by 119,000, where the BLS had overestimated standard payroll employment growth.

The preliminary announcement of the benchmark revision to March 2014 payrolls was for a relatively insignificant upside adjustment of 7,000 (see Commentary No. 660).

With the March 2013 revision, though, the BLS separately redefined the payroll survey so as to include 466,000 workers who had been in a category not previously counted in payroll employment. The latter event was little more than a gimmicked, upside fudge-factor, used to mask the effects of the regular downside revisions to employment surveying, and likely is the excuse behind the increase in the annual bias factor, where the new category cannot be surveyed easily or regularly by the BLS.

Indeed, particularly unusual with that last revision is that despite the BLS modeling having overstated jobs creation through March 2013 by 119,000, adjustment to the annual upside biases added into payroll estimation process each month, thereafter, was increased initially by about 150,000 (currently about 107,000) on an annual basis, instead of being reduced, which would have been expected otherwise (see short-term graph of nonfarm payrolls and comments on payroll levels early in this broader section).

Historically, the upside-bias process was created simply by adding in a monthly "bias factor," so as to prevent the otherwise potential political embarrassment to the BLS of understating monthly jobs growth. The "bias factor" process resulted from such an actual embarrassment, with the underestimation of jobs growth coming out of the 1983 recession. That process eventually was recast as the now infamous Birth-Death Model (BDM), which purportedly models the effects of new business creation versus existing business bankruptcies.

December 2014 Bias. The not-seasonally-adjusted December 2014 bias was a negative monthly add-factor of 20,000 (-20,000), versus a post-2013 benchmark negative bias of 12,000 (-12,000) in December 2013, versus a monthly add factor of 8,000 in November 2014. The aggregate upside bias for the trailing twelve months was 731,000 as of December 2014, from the pre-benchmark 624,000 twelve-month aggregate as of December 2013, or a monthly average of 61,000 (52,000 pre-benchmark) jobs created out of thin air, on top of some indeterminable amount of other jobs that are lost in the economy from business closings. Those losses simply are assumed away by the BLS in the BDM, as discussed below.

Problems with the Model. The aggregated upside annual reporting bias in the BDM reflects an ongoing assumption of a net positive jobs creation by new companies versus those going out of business. Such becomes a self-fulfilling system, as the upside biases boost reporting for financial-market and political needs, with relatively good headline data, while often also setting up downside benchmark revisions for the next year, which traditionally are ignored by the media and the politicians. Where the BLS cannot measure meaningfully the impact of jobs loss and jobs creation from employers starting up or going out of business, on a timely basis (within at least five years, if ever), or by changes in household employment that just have been incorporated into the redefined payroll series, such information is guesstimated by the BLS along with the addition of a bias-factor generated by the BDM.

Positive assumptions—commonly built into government statistical reporting and modeling—tend to result in overstated official estimates of general economic growth. Along with these happy guesstimates, there usually are underlying assumptions of perpetual economic growth in most models. Accordingly, the functioning and relevance of those models become impaired during periods of economic downturn, and the current, ongoing downturn has been the most severe—in depth as well as duration—since the Great Depression.

Indeed, historically, the BDM biases have tended to overstate payroll employment levels—to understate employment declines—during recessions. There is a faulty underlying premise here that jobs created by start-up companies in this downturn have more than offset jobs lost by companies going out of business. Recent studies have suggested that there is a net jobs loss, not gain, in this circumstance. So, if a company fails to report its payrolls because it has gone out of business (or has been devastated by a hurricane), the BLS assumes the firm still has its previously-reported employees and adjusts those numbers for the trend in the company’s industry.

Further, the presumed net additional “surplus” jobs created by start-up firms are added on to the payroll estimates each month as a special add-factor. These add-factors are set now to add an average of 61,000 jobs per month in the current year. In current reporting, the aggregate average overstatement of employment change easily exceeds 200,000 jobs per month.

HOUSEHOLD SURVEY DETAILS.

Falsification of Household-Survey Data, and Call for Help. Previously discussed, as detailed in Commentary No. 669, significant issues as to falsification of the data gathered in the monthly Current Population Survey (CPS), conducted by the Census Bureau, have been raised in the press and have been under investigation by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform and the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. The CPS is the source of the household survey used by the BLS in estimating monthly unemployment, employment, etc. Accordingly, the statistical significance of the headline reporting detail here is open to serious question.

Request for Help from John Crudele of the New York Post. John Crudele of the New York Post, who broke the story that triggered the Congressional investigation, has asked for interested parties to contact Congressman Jason Chaffetz (R-Utah), new head of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, at (801) 851-2500, to request that he continue probing the U.S. Census Bureau on the data falsification issue. Further detail, and updated background and status of the investigation are found here:

http://nypost.com/2015/01/06/call-congressman-for-some-good-common-census/

Benchmark Revision versus Concurrent Seasonal Adjustments at the BLS. Beyond potential quality issues of the CPS surveying process for the household survey, the BLS already has had in place reporting practices to make the seasonally-adjusted household-survey data virtually meaningless in terms of month-to-month change or comparison. The monthly concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustment process used in generating the headline numbers regenerates all seasonal factors every month, unique to the most-recent month. Yet, the revamped and consistent, seasonally-adjusted, historical household survey detail is not published, except once per year, in December, as reviewed in the Opening Comments for this month’s and year’s reporting. All the historical data will shift anew with the subsequent monthly reporting in January, but what would be new historical detail, consistent with that January reporting never will be published.

This means simply that other than for today’s one-time benchmarked 0.2% decline in headline December U.3 unemployment to 5.6%, from 5.8%, no one in the public knows whether a headline 0.2% (-0.2%) decline in monthly unemployment really is that, or if it is a 0.2% increase. Only the BLS knows for sure, and the Bureau will not talk about it.

Consider that last month, the seasonally-adjusted headline unemployment rate of 5.8% for November 2014 was based on a set of seasonal adjustments unique to November 2014, and, at the same time, the adjusted unemployment rate of 5.8% for October, was unique to October’s reporting. Detail as to what would have been an October unemployment rate consistent the November calculation never will be made public. Today’s December 2014 reporting detail and seasonal-adjustment revisions, however, showed all the reporting of the last five years on a consistent basis (a period of comparability that holds for only one month per year).

Consistent with December reporting of 5.6%, November was 5.8%, but October was 5.7%. So based on consistent reporting with December, the headline U.3 unemployment rate rose by 0.1% in November, instead of being unchanged, as reported with November headline numbers. Again, whatever the actual October-to-November change was, based on November instead of December reporting, is not and will not be known by the public.

The only difference between the different monthly headline reportings, was the shifting and always-inconsistent (except for December) monthly seasonal adjustments. The unadjusted data never are revised. Accordingly, other than December reporting each year, every month going back for at least five years of BLS accounting is not comparable with any other month on a seasonally-adjusted basis. Again, the historical month-to-month changes are revised every month, but not reported to the public. This is done deliberately by the BLS, where consistent and comparable, monthly historical data are being calculated by, and are known to the Bureau.

Headline Household Employment. The household survey counts the number of people with jobs, as opposed to the payroll survey that counts the number of jobs (including multiple-job holders more than once). On one-time comparable basis, headline December 2014 employment increased by 111,000, with November having increased by a revised 71,000 (previously 4,000). Again, the November revision was due only to the irregularly shifting seasonal factors seen on a consistent basis but once per year. The employment changes were in the context of a decline in December unemployment by 403,000 (-403,000), versus a revised increase in November unemployment of 88,000 (previously up by 115,000). Employment levels are plotted in graphs along with payrolls in the PAYROLL EMPLOYMENT section.

With 403,000 dropping from the unemployment rolls, but with only a gain of 111,000 in employed persons in December, the number of individuals rolling over from headline U.3 unemployment to short-term discouraged workers in U.6 increased, as did an increasing number of short-term discouraged workers in U.6, roll over into long-term discouraged-worker status in the broader ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure.

Headline Unemployment Rates. In the context of the preceding background, the headline December 2014 unemployment (U.3) rate decreased by 0.24-percentage point to 5.56% from a revised 5.80% (previously 5.82%) in November. Technically that was a statistically-significant change, where the official 95% confidence interval around the monthly change in headline U.3 is +/- 0.23-percentage point. That is meaningless, usually, in the context of the comparative month-to-month reporting-inconsistencies created by the concurrent-seasonal factors, let alone new questions as to general survey accuracy and significance. Consistent month-to-month reporting means only that the data are comparable in the context of their method of preparation. It does not mean, however, that the numbers are accurate estimates of employment activity.

On an unadjusted basis, the unemployment rates are not revised and at least are consistent in reporting methodology. December’s unadjusted U.3 unemployment rate was 5.4%, down from 5.5% in November.

U.6 Unemployment Rate. The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (i.e., they cannot find a full-time job).

With a small, seasonally-adjusted decline in people working part-time for economic reasons and a more-than-offsetting increase in discouraged workers and those marginally attached to the workforce (unadjusted), headline December 2014 U.6 unemployment declined to 11.20%, from a revised 11.38% (previously 11.40%) in November. The unadjusted U.6 increased to 11.1% in December, from 11.0% in November.

Discouraged Workers. The count of short-term discouraged workers in December 2014 (never seasonally-adjusted) rose to 740,000, from 698,000 in November, versus 770,000 in October and 698,000 in September. The latest, official discouraged-worker number reflected the flow of the unemployed—increasingly giving up looking for work—leaving the headline U.3 unemployment category and being rolled into the U.6 measure as short-term “discouraged workers,” net of the further increase in the number of those moving from short-term discouraged-worker status into the netherworld of long-term discouraged-worker status.

It is the long-term discouraged-worker category that defines the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure. There appears to be a relatively heavy, continuing rollover from the short-term to the long-term category, with the ShadowStats measure encompassing U.6 and the short-term discouraged workers, plus the long-term discouraged workers.

In 1994, “discouraged workers”—those who had given up looking for a job because there were no jobs to be had—were redefined so as to be counted only if they had been “discouraged” for less than a year. This time qualification defined away a large number of long-term discouraged workers. The remaining short-term discouraged workers (those discouraged less than a year) were included in U.6.

ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Rate. Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the growing ranks of excluded, long-term discouraged workers, broad unemployment—more in line with common experience, as estimated by the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure—eased to 23.0% in December, versus a revised 23.1% (previously 23.0%) in November, and down from a revised series high (back to 1994) of 23.3% seen variously in June, October and December 2013. Previously, the high had been 23.4% in October 2013. The ShadowStats estimate reflects the increasing toll of unemployed leaving the headline labor force. Where the ShadowStats-Alternate estimate generally is built on top of the official U.6 reporting, it tends to follow its relative monthly movements and particularly its annual revisions. Accordingly, the alternate measure often will suffer some of the same seasonal-adjustment woes that afflict the base series, again, including underlying annual revisions.

[The remaining text in this Household Survey section is unchanged from the Commentary covering the November 2014 labor data, except for underlined language on further related graphs.] As seen in the usual graph of the various unemployment measures (in the Opening Comments), there continues to be a noticeable divergence in the ShadowStats series versus U.6, and the ShadowStats series and U.6 versus U.3. The reason for this is that U.6, again, only includes discouraged workers who have been discouraged for less than a year. As the discouraged-worker status ages, those that go beyond one year fall off the government counting, even as new workers enter “discouraged” status. A similar pattern of U.3 unemployed becoming “discouraged” and moving into the U.6 category also accounts for the early divergence between the U.6 and U.3 categories.

With the continual rollover, the flow of headline workers continues into the short-term discouraged workers category (U.6), and from U.6 into long-term discouraged worker status (a ShadowStats measure). There was a lag in this happening as those having difficulty during the early months of the economic collapse, first moved into short-term discouraged status, and then, a year later into long–term discouraged status, hence the lack of earlier divergence between the series. The movement of the discouraged unemployed out of the headline labor force has been accelerating. While there is attrition in long-term discouraged numbers, there is no set cut off where the long-term discouraged workers cease to exist. See the Alternate Data tab for historical detail.

Generally, where the U.6 largely encompasses U.3, the ShadowStats measure encompasses U.6. To the extent that the decline in U.3 reflects unemployed moving into U.6, or the decline in U.6 reflects short-term discouraged workers moving into the ShadowStats number, the ShadowStats number continues to encompass all the unemployed, irrespective of the series from which they otherwise may have been ejected.

Three further related graphs, also found in the Opening Comments section, are of the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure, with an inverted scale, the employment-to-population ratio, which has a high correlation with the inverted ShadowStats measure, and participation rate, a measure commonly touted by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen (see the pending Special Report).

Great Depression Comparisons. As discussed in the regular Commentaries covering the monthly unemployment circumstance, an unemployment rate above 23% might raise questions in terms of a comparison with the purported peak unemployment in the Great Depression (1933) of 25%. Hard estimates of the ShadowStats series are difficult to generate on a regular monthly basis before 1994, given the reporting inconsistencies created by the BLS when it revamped unemployment reporting at that time. Nonetheless, as best estimated, the current ShadowStats level likely is about as bad as the peak actual unemployment seen in the 1973-to-1975 recession and in the double-dip recession of the early-1980s.

The Great Depression unemployment rate of 25% was estimated well after the fact, with 27% of those employed working on farms. Today, less than 2% of the employed work on farms. Accordingly, a better measure for comparison with the ShadowStats number would be the Great Depression peak in the nonfarm unemployment rate in 1933 of roughly 34% to 35%.

__________

WEEK AHEAD

Against Overly-Optimistic Expectations, Economic Releases and Revisions in the Months Ahead Should Trend Much Weaker; Inflation Releases Should Be Increasingly Stronger after the Impact of Temporary Oil-Price Declines. Shifting some to the upside, again, from the downside, amidst wide fluctuations in the numbers, market expectations for business activity remain overly optimistic in the extreme. They exceed any potential, underlying economic reality. Downside corrective revisions and an accelerating pace of downturn in broad-based headline economic reporting should hammer those expectations in the next several months. Recent GDP excesses, however, will not face downside revisions until the July 30, 2015 benchmark revision to that series (see Commentary No. 684).

Headline consumer inflation—dominated by gasoline and other oil-price related commodities—should hit a near-term bottom in the next two months. Significant upside inflation pressures should resume when oil prices begin their rebound, a process that should be accelerated rapidly by an eventual sharp downturn in the exchange-rate value of the U.S. dollar. These areas, the general economic outlook and longer range reporting trends are reviewed broadly in the pending Special Commentary.

A Note on Reporting-Quality Issues and Systemic-Reporting Biases. Significant reporting-quality problems remain with most major economic series. Beyond gimmicked changes to reporting methodologies of the last several decades, ongoing headline reporting issues are tied largely to systemic distortions of seasonal adjustments. Data instabilities were induced partially by the still-evolving economic turmoil of the last eight years, which has been without precedent in the post-World War II era of modern economic reporting. The severity and ongoing nature of the downturn provide particularly unstable headline economic results, when concurrent seasonal adjustments are used (as with retail sales, durable goods orders, employment, and unemployment data). Combined with recent allegations (see Commentary No. 669 and today’s HOUSEHOLD SURVEY section) of Census Bureau falsification of data in its monthly Current Population Survey (the source for the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Household Survey), these issues have thrown into question the statistical-significance of the headline month-to-month reporting for many popular economic series. Again, new issues tied to GDP reporting are discussed in the pending Special Commentary and in prior Commentary No. 684.

PENDING RELEASES:

Retail Sales (December 2014). The Census Bureau has scheduled the release of December 2014 retail sales for Wednesday, January 14th. Early market expectations appear to be near unchanged for this most-significant of retail sales months. A downside reporting surprise to developing market expectations usually is a good bet.

The consumer remains in an extreme liquidity bind, as discussed in Commentary No. 680), and as detailed more extensively in the pending Special Commentary. Without sustained growth in real income, and without the ability and/or willingness to take on meaningful new debt to make up for the income shortfall, the U.S. consumer is unable to sustain positive growth in domestic personal consumption, including retail sales. Accordingly, the headline December retail sales number is at high risk of showing an outright month-to-month contraction (in nominal terms, before inflation adjustment). At the same time, look for downside revisions to the previously-reported November and October detail.

The December CPI-U estimate (due for publication on January 16th, with coverage in Commentary No. 689 on the same date) will determine the level of inflation-adjusted, or real, retail sales for the month. The headline CPI-U, however, likely contracted month-to-month in December, as discussed in the ensuing CPI preview, which would tend to boost the headline real retail sales activity in December, versus the likely weaker nominal headline reporting.

Producer Price Index—PPI (December 2014). The December 2014 PPI is scheduled for release on Thursday, January 15th by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Detail, however, will be covered in ShadowStats Commentary No. 689 of Friday, January 16th.

Early consensus expectations appear to be for a large monthly contraction in the December PPI, perhaps double the pace of the headline, seasonally-adjusted 0.2% (-0.2%) in November, reflecting collapsing oil prices. Those expectations are reasonable, under the circumstances.

The energy sector, once again, should be the dominant downside component in the headline monthly data. Based on the two most widely followed oil contracts, not-seasonally-adjusted, monthly-average oil prices fell by 21.5% (-21.5%) and by 21.8% (-21.8%) in the month of December, along with a 12.2% (-12.2%) monthly drop in unadjusted average retail-gasoline prices. PPI seasonal adjustments for energy costs in December should provide negligible offset to the unadjusted plunge in energy-related prices.

Inflation in food, “core” goods (everything but food and energy), and some still spreading inflationary impact from hard-goods into the soft-services sector, or dropping costs helping to increase margins, could be mitigating factors, again.

The wildcard in this revamped PPI remains the recently-added services sector, which largely is unpredictable, volatile and of limited meaning, due to its inflation measurements having minimal relationship to real-world activity. Nonetheless, this new services sector has a greater weighting in the PPI calculation than does the goods sector

The services series, in theory, is much-less dependent on the increasingly “antiquated” concepts of oil, food and “core” (ex-food and energy) inflation of the “hard” production-based economy. Yet, services costs recently had reflected spreading, general inflationary pressures—and shrinking profit margins—from rising prices in that hard economy. That reversed some with lower energy costs boosting margins. Where rising margins are counted as inflationary in the new system, such has the potential to generate upside surprises. This general approach to "wholesale" inflation is of questionable merit.

Consumer Price Index—CPI (December 2014). The December 2014 CPI is scheduled for release on Friday, January 16th, by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The headline CPI-U should contract month-to month, reflecting declining the sharp drop in gasoline prices. Early expectations of a headline monthly decline of 0.3% (-0.3%) for the CPI-U are not unreasonable. A 0.4% headline contraction is possible. In the CPI-W, which is more heavily weighted for gasoline, the headline decline could be greater. As oil prices bottom out in the near future, so too should gasoline and its current negative impact on the headline CPI-U.

Plunging again, average gasoline prices fell by 12.18% (-12.18%) month-to-month in December, on a not-seasonally-adjusted basis, per the Department of Energy (DOE). While BLS seasonal adjustments to gasoline prices should be positive in December, they still should leave adjusted monthly gasoline prices down by roughly 10.3% (-10.3%) or so for the month. By itself, such an adjusted decline in gasoline prices would leave the headline CPI-U down by something shy of 0.5% (-0.5%).

Higher food and “core” (net of food and energy) inflation, however, should still some of the negative energy number, leading to a headline monthly contraction of 0.3% to 0.4% (-0.3% to -0.4%) in the December CPI-U.

Annual Inflation Rate. Year-to-year, CPI-U inflation would increase or decrease in December 2014 reporting, dependent on the seasonally-adjusted monthly change, versus an adjusted 0.24% monthly inflation reported for December 2013. The adjusted change is used here, since that is how consensus expectations are expressed. To approximate the annual unadjusted inflation rate for December 2014, the difference in December’s headline monthly change (or forecast of same), versus the year-ago monthly change, should be added to or subtracted directly from the November 2014 annual inflation rate of 1.32%. For example, if the headline, seasonally adjusted CPI-U declined month-to-month by 0.3% (-0.3%), unadjusted annual inflation would fall to about 0.8%.

Index of Industrial Production (December 2014). On Friday, January 16th, the Federal Reserve Board will release its estimate of the December 2014 index of industrial production.

Early market expectations apparently favor some pullback in December from November’s headline booming growth. Risks are high for a downside surprise in the headline reporting, very possibly outright monthly contraction, along with downside revisions to prior reporting.

__________