No. 779: December Labor Numbers, Shifting Monetary Conditions and Money Supply M3

COMMENTARY NUMBER 779

December Labor Numbers, Shifting Monetary Conditions and Money Supply M3

January 9, 2016

___________

Something Afoot in the Banking System?

Post-FOMC Rate Hike, Excess Reserves in Historic Plunge;

Monetary Base Dropped to 28-Month Low in Record Annual Decline

December Year-to-Year Broad Money Supply Growth

Fell to 4.5% from 5.2% in November

Employment and Unemployment Reality Remained Bleak

Year-to-Year Payroll Growth Held at 19-Month Low

Headline Payrolls Heavily Skewed by Unpublished Seasonal Shifts

Household-Survey Revisions Were Unusually Minimal

November 2015 Unemployment Levels Unchanged:

U.3 held at 5.0%; U.6 at 9.9%, and ShadowStats at 22.9%

Fourth-Quarter Industrial Production Faces

Quarterly and Annual Contractions in Week Ahead

___________

PLEASE NOTE: The next regular Commentary, scheduled for Friday, January 15th, will cover December Retail Sales, Industrial Production and the Producer Price Index (PPI). Review of 2015 and preview of 2016: No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary.

Best wishes to all — John Williams

OPENING COMMENTS AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A Monetary System in Flux; Negligible Unemployment Revisions. Originally planned for yesterday, today’s Commentary had been set for late-in-the-day publication, based on extensive review necessary for the annual revisions to the Household-Survey data (unemployment, employment, etc.), published yesterday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), in conjunction with its regular release of the December 2015 headline employment and unemployment numbers.

This Commentary, however, was pushed overnight, to January 9th, based upon unfolding and unusual post-FOMC developments in the U.S. monetary system, reviewed and graphed in the Monetary Conditions section, Hyperinflation Watch. The monetary base and excess reserves have had sharp near-term declines, suggestive of possible, unusual banking-system developments. Separately, annual growth in the broad money supply is slowing at an increasing pace.

Household-Survey Revisions Were Unusually Minimal. The December 2015 annual Household–Survey revisions to five years of seasonally-adjusted data are reflected in all related numerical and graphic detail of this Commentary and in the updated database for U.3, U.6 and ShadowStats unemployment detail found in Alternate Unemployment on the Alternate Data tab at www.ShadowStats.com.

The headline revisions, however, were minimal, the with effect that there were no revisions to the seasonally-adjusted, monthly headline U.3 unemployment rate at the first decimal point. The broader U.6 measure had seven (out of sixty) monthly shifts that rounded up or down by 0.1% with about equal frequency. The ShadowStats measure revised higher by 0.1% in September 2013 and September 2014, and down by 0.1% in May 2015.

Where all related graphs are shown as “revised,” those graphs do not include comparative before and after plots, simply because the visual differences in such graphs would have been nil. All the Household-Survey inconsistencies, however, return with the January 2016 detail, due for release on February 6th.

Today’s Commentary (January 9th). The balance of these Opening Comments provides summary coverage of the December Employment and Unemployment data.

Monetary Conditions in the Hyperinflation Watch reviews the post-FOMC monetary-base contractions declines in excess reserves, and updated Fed policies, along with a rapid slowing in annual M3 growth (ShadowStats Ongoing-M3 Measure). The Hyperinflation Outlook Summary, updated in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary of No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary, will be condensed, extracted and included soon in these regular Commentaries.

The Week Ahead previews Friday’s (January 15th) reporting of December 2015 Retail Sales, Industrial Production and the Producer Price Index (PPI). In particular, third-quarter 2015 Industrial Production reporting is a virtual certainty to suffer formal quarterly and annual contractions.

Employment and Unemployment—December 2015—Despite Annual Household-Survey Revisions, Headline Labor Conditions Remained Bleak and Seriously Flawed. Underlying reality for U.S. labor conditions in December 2015 remained in the realm of a 22.9% broad unemployment rate, with headline monthly payroll employment growth close to flat, as reviewed in the main text. Annual revisions to the Household-Survey details were minimal, specifically including the various unemployment measures.

Unemployment. Reality aside, the headline (U.3) unemployment rate (Household-Survey) held even at a rounded 5.0% in December 2015, for a third, consecutive month, down from an April 2010 peak of 10.0%. This headline rate has been helped meaningfully by unemployed individuals being defined out of the headline labor force, instead of being reflected in new, non-existent gainful employment. The broader U.6 unemployment measure, including those marginally attached to the workforce (including short-term discouraged workers) and those working part-time for economic reasons, held at 9.9% in December 2015, the same level as in November and up from 9.8% in October.

Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of long-term discouraged workers (excluded from the government’s unemployment calculations)—a broad measure more in line with common experience—the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate held at 22.9% in December 2015. The same level as in November, it was up from a near-term low of 22.8% in October, and down from the series high reading of 23.3% in December 2013.

Payroll Employment. In terms of nonfarm payroll employment (Payroll-Survey), headline December jobs increased by a greater-than-expected 292,000, up by 342,000 net of prior period revisions. The headline payroll reporting also was in the context of continued, unusual shifts in seasonal-adjustment patterns. Subject to the usual reporting biases and distortions, headline December payrolls were not comparable to reporting in October and before.

Specifically, the headline Payroll-Survey numbers were distorted by unreported inconsistencies in the historical data, again as generated by BLS reporting of its concurrent seasonal-factor adjustment modeling. Separately, the jobs gains were inflated heavily by the monthly add-factors in the Birth-Death Model (BDM). With the aggregate, monthly upside biases well in excess of 200,000 jobs, the actual December 2015 headline payroll gain most likely was close to flat. On a not-seasonally-adjusted basis, however, recent slowing in year-to-year payroll growth held steady, with December annual growth at a nineteen-month low.

Headline Payroll Detail. In the context of upside revisions to relative employment activity in November and October, the seasonally-adjusted, headline payroll gain for December 2015 was a stronger-than-expected 292,000 jobs. Net of prior-period revisions, the gain in December payroll employment was 342,000. The headline 292,000 increase in December followed an upwardly revised 252,000 gain in November, and an upwardly-revised fraudulent gain of 307,000 in October.

October’s month-to-month gain really was 292,000 jobs, on a consistent-reporting basis. Although the BLS deliberately misreported the headline monthly detail prior to November, the actual earlier numbers can be calculated using material available from the BLS, and the differences easily can run up to 100,000 jobs per month versus official headline reporting (see the Reporting Detail).

Beyond excessive upside add-factor biases built into the monthly calculations (see the Birth-Death Model section), the problem remains that payroll employment counts the number of jobs, not the number of people who are employed. Much of that payroll “jobs” growth is in multiple part-time jobs—many taken on for economic reasons—where full-time employment has been desired but could not be found.

Again, irrespective of all the games playing with the seasonally-adjusted detail, annual growth in the headline unadjusted payroll numbers is not confirming the adjusted “boom” in the headline payrolls.

Annual Percent Change in Headline Payrolls—Slowing Growth. Not-seasonally-adjusted, year-to-year change in payroll employment is untouched by the concurrent-seasonal-adjustment issues, so the monthly comparisons of year-to-year change at least are reported on a consistent basis.

Still, last year’s 2014 benchmarked surges built into headline payroll activity, boosted annual growth in unadjusted payrolls, setting a post-recession high of 2.39% in February 2015. Such then was the strongest annual growth since June 2000 (another recession), but subsequent annual growth has slowed. Year-to-year nonfarm payroll growth in December 2015 held at 1.91%, the same level as a revised 1.91% in November 2015, down from a revised annual gain of 1.96% in October 2015, and unrevised gains of 1.92% in September 2015, 2.03% in August 2015 and 2.18% in July 2015. November and December 2015 annual growth readings were tied as the weakest of the last nineteen months.

Downside 2015 Payroll Benchmark Revision, Initially Estimated at 208,000 (-208,000), Looms for Next Month. The advance estimate of the 2015 benchmarking for payroll employment, announced on September 17th, indicated a downside revision of 208,000 (-208,000) jobs to the base March 2015 payroll employment levels (see Commentary No. 753 and the Birth-death Model section). The final benchmark revision for 2015 will be published along with headline January data on February 5, 2016, including corrections to earnings data warped by “processing errors” in the 2009 benchmarking.

Payroll Graphs in the Reporting Detail Section. Regular plots of both the level and annual change in monthly nonfarm payrolls are found in the Reporting Detail, Graphs 12 to 13 and 17 to 18. Also graphed and discussed there are details of the monthly construction payroll data, comparative graphs of nonfarm payrolls, the full-employment series from the Household-Survey, and detail of seasonal-factor distortions from the reporting (or lack of reporting) of concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustments in headline payroll employment.

Counting All Discouraged Workers, December 2015 Unemployment Was at About 22.9%. Discussed frequently in these Commentaries on monthly unemployment conditions, what removes headline-unemployment reporting from common experience and broad, underlying economic reality, simply is definitional. To be counted among the headline unemployed (U.3), an individual has to have looked for work actively within the four weeks prior to the unemployment survey. If the active search for work was in the last year, but not in the last four weeks, the individual is considered a “discouraged worker” by the BLS, not counted in the headline labor force. ShadowStats defines that group as “short-term discouraged workers,” as opposed to those who, after one year, no longer are counted by the government and enter the realm of “long-term discouraged workers,” as defined and counted by ShadowStats (see the extended comments in the ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Measure in the Reporting Detail).

In the ongoing economic collapse into 2008 and 2009, and the non-recovery thereafter, the broad drop in the U.3 unemployment rate from its headline peak of 10.0% in 2009, to holding at a “post-recession” low of 5.0% in each of October, November and December 2015, has been due largely to unemployed giving up looking for work (common in severe conditions). Those giving up looking for work are redefined out of headline reporting and the labor force, as discouraged workers. The declines in the headline unemployment reflect same, much more so than the unemployed finding new and gainful employment.

As new discouraged workers move regularly from U.3 into U.6 unemployment accounting, those who have been discouraged for one year are dropped from the U.6 measure. As a result, the U.6 measure has been declining along with U.3 for some time, but those being pushed out of U.6 still are counted in the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure, which has remained relatively steady, near its historic-high rate for the last couple of years.

Moving on top of U.3, the broader U.6 unemployment rate—the government’s broadest unemployment measure—includes only the short-term discouraged workers (those marginally attached to the labor force). The still-broader ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure includes an estimate of all discouraged workers, including those discouraged for one year or more, as the BLS used to define and measure the series, before 1994.

Graph 1: Comparative Unemployment Rates U.3, U.6 and ShadowStats - Revised

Again, when the headline unemployed become “discouraged,” they are rolled over from U.3 to U.6. As the headline, short-term discouraged workers roll over into long-term discouraged status, they move into the ShadowStats measure, where they remain. Aside from attrition, they are not defined out of existence for political convenience, hence the longer-term divergence between the various unemployment rates. The resulting difference here is between headline-December 2015 unemployment rates of 5.0% (U.3) and 22.9% (ShadowStats).

Graph 1 reflects headline December 2015 U.3 unemployment at 5.01%, versus a revised 5.04% in November; headline December U.6 unemployment at 9.87%, versus a revised 9.89% in November; and the headline December ShadowStats unemployment estimate at 22.9%, holding at the same level as in November.

Graph 2: Inverted-Scale ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Measure

Graph 3: Civilian Employment-Population Ratio

The Graphs 2 to 4 reflect longer-term unemployment and discouraged-worker conditions. While each of these series was revised minimally in the headline annual revisions of the BLS’s Household Survey, the differences had negligible visual impact on these graphs. Graph 2 is of the ShadowStats unemployment measure, with an inverted scale. The higher the unemployment rate, the weaker will be the economy, so the inverted plot tends to move in tandem with plots of most economic statistics, where a lower number means a weaker economy.

The inverted-scale of the ShadowStats unemployment measure also tends to move with the employment-to-population ratio, which notched minimally higher, again, in December 2015, though still near its post-1994 record low, the historic low and bottom since economic collapse (only the period following the series redefinition in 1994 reflects consistent reporting), as shown in Graph 3. The labor force containing all unemployed (including total discouraged workers) plus the employed, however, tends to be correlated with the population, so the employment-to-population ratio remains something of a surrogate indicator of broad unemployment, and it has a strong correlation with the ShadowStats unemployment measure.

Shown in Graph 4, the December 2015 participation rate also ticked minimally higher, off the historic low hit in September 2015 (again, pre-1994 estimates are not consistent with current reporting). The labor force used in the participation-rate calculation is the headline employment plus U.3 unemployment. As with the Graph 3 of employment-to-population, its holding at a post-1994 low in current reporting is another indication of problems with long-term discouraged workers, the loss of whom continues to shrink the headline (U.3) labor force, and the plotted ratio.

Graph 4: Participation Rate

Graphs 1 through 4 reflect data available in consistent detail back to the 1994 redefinitions of the Household Survey and the related employment and unemployment measures. Before 1994, employment and unemployment data consistent with December’s Household-Survey reporting simply are not available, irrespective of protestations to the contrary by the BLS. Separately, consider Graph 5, which shows the ShadowStats version of the GDP, also from 1994 to date, where the GDP is corrected for the understatement of inflation used in deflating that series (a detailed description and related links are found in GDP Commentary No 775).

Graph 5: Corrected Real GDP

Graph 6: Real S&P 500 Sales Adjusted for Share Buybacks (2000 - 2015), Indexed to January 2000 = 100

In particular, the general patterns of activity seen in Graphs 3 and 4 generally are mirrored in Graph 5 of the “corrected” GDP and also largely are consistent with the post-2000 period shown in Graph 6 of real S&P 500 revenues from No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary. Graph 6 initially was prepared with a quarterly data range from 2000 to third-quarter 2015, but the time scale of the plot has been shifted here back to 1994, so as to show the S&P 500 revenue detail on roughly a comparative, coincident basis with the detail in Graphs 2 to 5. Of note, unlike Graphs 2 to 5, Graph 6 is not seasonally adjusted.

Headline Unemployment Rates. At the first decimal point, the headline December 2015 unemployment rate (U.3) was unchanged, holding at 5.0% for the third month. At the second decimal point, headline December U.3 declined by 0.03-percentage point to 5.01% from a revised 5.04%. Technically, the headline December decline in U.3 was statistically-insignificant.

The headline change in U.3 usually is without meaning, given that the seasonally-adjusted, month-to-month details simply are not comparable, due to the BLS’s reporting methodology and use of concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors (see Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors in the Reporting Detail). Yet, the headline December 2015 Household-Survey reporting included annual revisions, with detail restated with consistent seasonally-adjusted history back for five years. This once-per-year revamping will revert to month-to-month non-comparability of the seasonally-adjusted historical numbers with subsequent January 2016 reporting. These quality issues remain separate from official questions raised as to falsification of the Current Population Survey (CPS), from which are derived the unemployment details.

On an unadjusted basis, the unemployment rates are not revised and always are consistent in post-1994 reporting methodology. The December 2015 unadjusted U.3 unemployment rate eased to 4.80% versus 4.81% in November.

The negligible decline in the seasonally-adjusted, headline December 2015 U.3 unemployment rate reflected a decline of 20,000 (-20,000) unemployed individuals with a gain of 485,000 employed, and an aggregate gain of 466,000 in the labor force. The changes here are suggestive of poor-quality seasonal adjustments tied to the holiday season, which should tend to reverse in subsequent reporting.

New discouraged and otherwise marginally-attached workers always are moving into U.6-unemployment accounting from U.3, while those who have been discouraged for one year continuously are dropped from the U.6 measure. As a result, the U.6 measure has been easing along with U.3, for a while, but those pushed out of U.6 still are counted in the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate, which has remained stable.

U.6 Unemployment Rate. The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (i.e., they cannot find a full-time job).

With a negligible decline in the underlying seasonally-adjusted U.3 rate, a small decline in the adjusted number of people working part-time for economic reasons, and a more-than-offsetting gain in those marginally attached to the workforce (short-term discouraged workers rose for the month), headline December 2015 U.6 unemployment softened negligibly to 9.87%. That was against a revised 9.89% in November. The unadjusted U.6 unemployment rate was at 9.78% in December 2015, versus 9.59% in November.

ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Estimate. Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the still-growing ranks of excluded, long-term discouraged workers—a broad unemployment measure more in line with common experience—the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate held at 22.9% in December 2015, the same as in November.

Off the October 2015 near-term low of 22.8%, the ShadowStats December 2015 reading still was down by 40 basis points or by 0.40% (-0.40%) from the 23.3% series high in December 2013. In contrast, the headline U.3 reading for December 2015 of 5.0% was tied with the October and November 2015 readings as the lowest rate since February of 2008, down from its 10.0% peak in April 2010 by a full 500 (-500) basis points or 5.00% (-5.00%).

[The Reporting Detail section includes further material and graphs on December labor conditions.]

__________

HYPERINFLATION WATCH

MONETARY CONDITIONS

With Excess Reserves in a Record Plunge, Monetary Base Takes a Post-FOMC Hit. Suggestive of post-FOMC systemic distortions or shifting patterns of banking activity, the St. Louis Fed’s monetary base declined to a seasonally-adjusted, 28-month low in the two-week period ended January 6, 2016. Plunging year-to-year by 7.4%, such was the steepest annual decline in the 30-year history of the series. Separately, annual growth in the broad U.S. Money supply—indicated by the ShadowStats-Ongoing M3 measure—has slowed rapidly. Where the monetary base once was the Fed’s primary tool for targeting money supply growth (pre-Panic of 2008), that relationship was destroyed post-2008 by the Fed’s paying interest on excess reserves, to induce depository-institution placement of same with the Fed.

The monetary base consists of cash in circulation plus reserve balances held by depository institutions (primarily commercial banks, including some foreign ones) at the Federal Reserve (FRB). At present, excess reserves (reserve balances in excess of required reserves) account for roughly 58.4% of the monetary base, followed by currency in circulation at 39.1% and surplus vault cash of 2.5% (based on FRB unadjusted reporting through January 6th). As a separate consideration, the Fed estimates that roughly 70% of U.S. currency in circulation is outside of the United States. The primary short-term volatility seen in the current monetary base comes from fluctuation in excess reserves.

Interest Rate Paid on Reserves Now Used for Setting the Federal Funds Rate. The primary motive at present for the depository institutions to hold excess reserves at the Fed is the interest paid on those deposits. In the post-Panic of 2008 environment, the interest rate paid by the Fed on reserves has become the Fed’s expressed primary tool for targeting the federal funds rate (see Fed Policy Normalization Plan - September 17, 2014).

The interest rate paid on reserves now is set at the upper limit of the targeted federal funds rate range. On December 16, 2015, the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised the interest rate paid on bank reserves to 0.50%, from 0.25%, along with an increase in the targeted federal funds rate by 25 basis points (0.25%) to a range of 0.25% to 0.50% (see FOMC Policy Change Implementation - December 16, 2015).

Such was the first hike in the federal funds rate since June 29, 2006, and the first change in the federal funds target rate (and the interest rate paid on reserves) since they had been set previously on December 16, 2008 at 0.00% to 0.25% (0.25% for reserves). Paying interest on reserves had been allowed in the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of October 2008.

Monetary Base Has Taken Something of a Hit. Noted in No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary of December 30th, the monetary base largely had been stable since the Fed stopped increasing its holdings of U.S. Treasuries late in 2014 (maturing issues still are rolled over). The monetary base during the last year had moved within a range of plus-or-minus 5% around the St. Louis Fed’s estimated 12-month average of $4.0 trillion. A sharp drop in the base (daily average) during the two-week period ended December 23, 2015, encompassing the December 16th FOMC rate-hike action, bore close watching.

Reported January 7th, a subsequent two-week plunge in the St. Louis Fed’s Monetary Base through January 6th, took the series to $3.650 trillion, well below its recent range, hitting a 28-month low. The year-to-year decline in the seasonally-adjusted bi-weekly number was the steepest drop in the 30-year history of the St. Louis Fed series, as can be seen in accompanying Graphs 7 and 8 of the level and annual change in the series.

Also per the St. Louis Fed, related excess reserves (not seasonally adjusted) declined by 12.6% (-12.6%), down by $304.1 (-$304.1) billion from the two-week period ended December 9th, which was the last measurement before the FOMC’s rate action, through the just-announced January 6th period [weekly data suggest that all the decline in reserves was post-FOMC]. For just the two-week period ended January 6th, the decline in excess reserves was $261.6 billion. Those declines, whether for two consecutive two-week periods, or for just one two-week period, were the largest such declines in the 30-year history of the bi-weekly series. The latest two-week period is highlighted in the lighter shade of blue in Graph 9.

[See Graphs 7 and 8 on Next Page]

Graph 7: Monetary Base Level, Bi-Weekly through January 6, 2016

Graph 8: Monetary Base, Year-to-Year Percent Change, through January 6, 2015

Graph 9: Excess Reserves, Bi-Weekly through January 6, 2016

Unusual Monetary-System Activity. The timing of severe shifts in excess-reserves activity is suspect, subsequent to the FOMC action. Suggested here is some post-FOMC systemic instability, which could right itself fairly rapidly, or perhaps some shift in commercial-banking activity that does not appear to have been planned by the Fed. The unusually-large drop in excess reserves does not appear to be of a seasonal nature. Details in Federal Reserve reporting of the next week or two should clarify whether these numbers are just passing through unusual volatility, or if there has been a shift in banking activity.

Discussed in No. 742 Special Commentary: A World Increasingly Out of Balance and No. 692 Special Commentary: 2015 - A World Out of Balance, the Federal Reserve’s practical, primary mission has been to keep the banking system solvent and afloat—irrespective of Congressional mandates on employment and inflation—but that was not working, coming into the Panic of 2008. Introduced in 2008, quantitative easing went through a number of phases, as reflected in the size of, and growth in, the monetary base shown in accompanying Graphs 7 and 8. Where such monetary-base expansion normally would have translated into extraordinary growth in the money supply, it did not.

The extraordinary level of asset purchases by the Fed did not flow through to the broad economy, because banks did not lend into the normal flow of commerce, and there was no resulting significant upside movement in money supply. Instead, banks turned the funds back to the Fed as excess reserves, earning interest and also providing some support to the stock market. As part of this process, the Fed ended up monetizing the bulk of the U.S. Treasury’s funding needs during the period of active buying of Treasury securities, paying back interest earned on those securities to the Treasury. The Fed continues to hold those assets, rolling over or reinvesting maturing instruments.

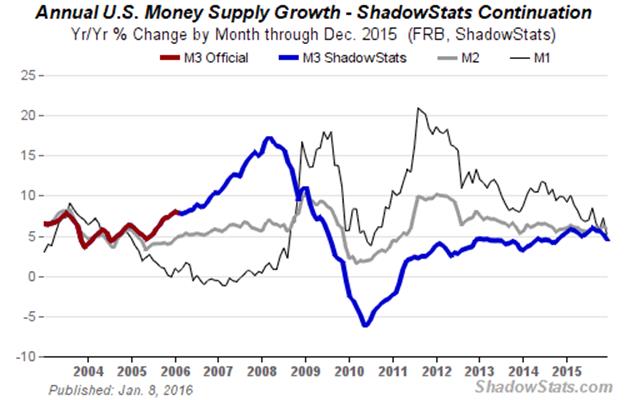

Annual M3 Growth Dropped to 4.5% in December 2015, versus 5.2% in November and a 6.0% Near-Term Peak in August 2015. Late in 2014, the Federal Reserve ceased net new purchases of U.S. Treasury securities as part of its quantitative easing QE3, but its outright holdings of Treasury securities have remained stable at $2.5 trillion levels, rolling over maturing issues. Again, where the monetary base during the last year had been plus-or-minus 5% around the St. Louis Fed’s estimated 12-month average of $4.0 trillion, that range was broken to the downside in the most-recent, two-week period.

Year-to-year to growth in broad money supply M3 also has been shifting to the downside, with the ShadowStats-Ongoing Measure, continuing to slow sharply from its six-year-high annual growth of 6.0% in August 2015, now standing at a fourteen-month-low annual growth of 4.5% December 2015.

ShadowStats estimates annual growth in broad money supply M3 at 4.5% in December 2015, down from an unrevised 5.2% in November 2015, a revised 5.6% [previously 5.5%] in October 2015, a revised 5.7% [previously 5.6%] in September 2015 and an unrevised 6.0% in August 2015.

On a month-to-month basis, December 2015 M3 declined by 0.1% (-0.1%), having gained 0.4% in each of November and October, and having declined in September 2015 by 0.1% (-0.1%). Other than for September and December 2015, the last time M3 declined month-to-month was in January 2011.

Graph 10: Comparative Money Supply M1, M2 and M3 Year-to-Year Change through November 2015

Annual Money Supply Growth Also Turned Lower for M2 and M1. Following are December 2015 year-to-year and month-to-month changes for the narrower M1 and M2 measures (M2 includes M1; M3 includes M2). See the Money Supply Special Report for full definitions of those measures. The slowing pace of annual growth in December M3 was seen in parallel with the narrower M2 and M1 measures. The latest estimates of annual growth for December 2015 M3, M2 and M1, and for earlier periods, also are available on the Alternate Data tab of www.ShadowStats.com.

Annual M2 growth in December 2015 eased to 6.0%, from a downwardly-revised 6.2% [previously 6.3%] in November 2015, with a month-to-month increase in December 2015 of 0.3%, versus a downwardly revised gain of 0.7% [previously 0.8%] in November. For M1, December 2015 year-to-year growth slowed to 5.2%, versus a downwardly-revised 7.3% [previously 7.4%] gain in November 2015, with a month-to-month decline of 0.8% (-0.8%) in December 2015, versus a downwardly revised monthly increase of 1.9% [previously 2.0%] in November.

HYPERINFLATION OUTLOOK SUMMARY

The Hyperinflation Outlook Summary was updated in the Opening Comments and Executive Summary of the December 30th No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary. That will be condensed, extracted and included here, soon, for the regular Commentaries.

__________

REPORTING DETAIL

EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT (December 2015)

Employment and Unemployment—December 2015—Despite Annual Revisions to Household-Survey Data, Headline Labor Conditions Remained Seriously Flawed. [Note: This section, through the PAYROLL SURVEY DETAIL, largely is repeated from the Opening Comments.] Underlying reality for U.S. labor conditions in December 2015 was in the realm of a 22.9% broad unemployment rate, with headline monthly payroll employment change likely close to flat, month-to-month, as reviewed in the main text. The annual revisions to the Household-Survey details, including headline unemployment measures were minimal.

Unemployment. Reality aside, the headline (U.3) unemployment rate (Household-Survey) held even at a rounded 5.0% for a third, consecutive month in December 2015, down from the April 2010 peak of 10.0%. The broader U.6 unemployment measure, including those marginally attached to the workforce (including short-term discouraged workers) and those working part-time for economic reasons, held at 9.9% in December 2015, the same level as in November and up from 9.8% in October.

Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the ever-growing ranks of long-term discouraged workers (excluded from government unemployment calculations)—a broad unemployment measure more in line with common experience—the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate held at 22.9% in December 2015, up from a near-term low of 22.8% in October, and down from the series high of 23.3% in December 2013.

Payrolls. In terms of payroll employment (Payroll-Survey), headline December jobs increased by a greater-than-expected 292,000, up by 342,000 net of prior period revisions. The headline payroll reporting also was in the context of continued unusual shifts in seasonal-adjustment patterns, subject to the usual reporting biases and distortions. Headline December payrolls were not comparable to reporting in October and before.

Specifically, the headline Payroll-Survey numbers were distorted by unreported inconsistencies in the historical data, again as generated by BLS reporting policies with its concurrent seasonal-factor adjustment modeling. Separately, the jobs gains were inflated meaningfully by the monthly add-factors in the Birth-Death Model (BDM). With the aggregate, monthly upside biases well in excess of 200,000 jobs, the actual December 2015 headline payroll gain most likely was close to flat. On a not-seasonally-adjusted basis, however, recent slowing in year-to-year payroll growth held steady, with December annual growth at a nineteen-month low.

PAYROLL SURVEY DETAIL. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published the headline payroll-employment detail for December 2015 on January 8th, showing stronger growth than expected by the markets, in the context of upside revisions to relative employment activity in November and October. Again, all that gimmicked nonsense aside, the headline unadjusted payroll numbers showed year-to-year annual payroll growth holding at a nineteen-month low.

Seasonally-adjusted, the headline payroll gain for December 2015 was 292,000 jobs +/- 129,000 (95% confidence interval). Net of prior-period revisions, the gain in December payroll employment was 342,000 jobs. The headline 292,000 increase in December followed an upwardly-revised 252,000 [previously 211,000] gain in November, and an upwardly-revised, fraudulent gain of 307,000 [previously up by 298,000, initially up by 271,000] in October payrolls.

The headline 307,000 monthly jobs gain in October really was a 292,000 gain, on a consistent-reporting basis. Although the BLS deliberately misreported the headline monthly detail prior to November, the actual earlier numbers can be calculated using material available from the BLS, and the differences easily can run up to 100,000 jobs per month versus official headline reporting.

Inconsistent, Non-Comparable and Deliberately-Misstated Monthly Changes for October 2015 and Before. Headline monthly payroll detail is not comparable with earlier months, back more than one month from the headline month, due to the BLS’s misuse of concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustments. Discussed in the Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors section, the reporting fraud comes not from the adjustment process, itself, but rather from the Bureau deliberately not publishing a consistent headline history, where a new history is generated and available each month, along with the recalculation of the seasonal factors unique to creating the current month’s headline detail.

As a result, the headline 292,000 monthly gain in December 2015 payrolls, and the revised 252,000 monthly gain in November were inconsistent with, and not comparable to, the revised headline October 2015 gain of 307,000. The October gain consistent with the new headline December-based detail was 292,000, some 15,000 less than the official headline number. Such, though, is just a regular misstatement of historical headline payroll activity by the BLS.

Consistent, actual prior history changes each month, revised along with the new seasonal-factor calculations that are unique to and determine the latest headline month’s numbers, but the BLS never publishes an historically-consistent series. The nature of what would be a consistent series was explored fully in Commentary No. 695. With revised differences shifting between months in 2014, as seen in Graphs19 and 20 in the section on Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors, parallel shifts tend to follow in the current seasonal factors for the same months in 2015, beyond what they would have been otherwise. Those shifts simply are inconsistent with the headline historical reporting, which does not get revised other than for the last two months of reporting. Most clearly seen in Graph 20, major revised shifts in the last fifteen months imply shifting seasonal factors in current reporting that otherwise are not based in any published, historical month-to-month patterns that are consistent with the latest seasonal factors, based on the initial estimates from the headline December 2015 payroll.

Downside 2015 Payroll Benchmark Revision of 208,000 (-208,000) Looms for Next Month. The advance estimate of the 2015 benchmarking for payroll employment, announced on September 17th, indicated a downside revision of 208,000 (-208,000) jobs to the base March 2015 payroll employment levels (see Commentary No. 753 and the Birth-death Model section). The final benchmark revision for 2015 will be published along with the January 2016 headline data on February 5, 2016 (see the Birth-Death Model section).

In addition, the BLS recently posted the following notice on its payroll employment homepage: “All employee hours and earnings data and related series from March 2006 through February 2009 for total private, private service-providing, education and health, membership associations and organizations and other services have been suppressed due to a data processing error introduced during the 2009 benchmark. Corrected data will be available on February 5, 2016 [again, the 2015 benchmark revision].”

Confidence Intervals. Where the current employment levels have been spiked by misleading and inconsistently-reported concurrent-seasonal-factor adjustments, the reporting issues suggest that a 95% confidence interval around the modeling of the monthly headline payroll gain should be well in excess of +/- 200,000, instead of the official +/- 129,000. Even if the data were reported on a comparable month-to-month basis, other reporting issues would prevent the indicated headline magnitudes of change from being significant. Encompassing Birth-Death Model biases, the confidence interval more appropriately should be in excess of +/- 300,000.

“Trend Model” for January 2016 Headline Payroll-Employment Change Indicates a xxx216,000 Jobs Gain. Discussed in Commentary No. 771 and as described generally in Payroll Trends, the trend indication from the BLS’s concurrent-seasonal-adjustment model—prepared by our affiliate www.ExpliStats.com—was for a December 2015 monthly payroll gain of 216,000, based on the BLS trend model structured into the actual headline reporting of November 2015. The detail here can be calculated independently, using material available from the BLS.

Consensus estimates tend to settle around the trend, and late-consensus estimates for December did, rising from somewhat lower early estimates. Nonetheless, the headline December payroll gain came in well above both trend and consensus estimates.

January 2016 Trend Estimate. Exclusive to ShadowStats subscribers, based on headline BLS modeling for December 2015 reporting, the ExpliStats trend number calculations suggest a BLS-based headline gain of 223,000 for January 2016. January consensus expectations could be expected to settle in around that level.

December Construction-Payroll Jumped Anew, As Construction Slowed. Accompanying Graph 11 of December 2015 Construction Payroll Employment activity updates Graph 10 in the Reporting Detail of prior Commentary No. 778 on Construction Spending. In theory, construction payroll levels should move closely with the inflation-adjusted aggregate construction spending series and the Housing Starts series (the latter measured in units rather than dollars). Headline month-to-month growth in construction employment was 0.7% in December 2015, versus unrevised monthly gains of 0.7% in November and 0.5% in October. The pace of monthly growth here has continued to pick up, at the same that headline construction activity and real construction spending have begun to turn down at an accelerating pace.

Graph 11: Construction Payroll Employment to December 2015

The December 2015 construction-payroll level of 6.538 million, showed a headline gain of 45,000 for the month, following a monthly gain of 48,000 [previously 46,000] jobs in November and a revised October gain of 35,000 [previously up by 34,000, initially up by 31,000].

Headline construction-payroll numbers remain heavily biased to the upside (officially bloated by 6,000 jobs per month, unofficially at an order of magnitude of 20,000 jobs per month). Nonetheless, total December 2015 construction jobs remained down by 15.4% (-15.4%) from the April 2006 pre-recession series peak.

Historical Payroll Levels. Payroll employment is a coincident indicator of economic activity, and irrespective of all the reporting issues with the series, payroll employment formally regained its pre-recession high in 2014, despite the GDP purportedly having done the same somewhat shy of three years earlier, back in 2011. Reflected in the next two graphs, headline payroll employment moved to above its pre-recession high in April 2014 (it had happened in May 2014, prior to the 2014 benchmark revisions published in February 2015), and it has continued to rise. Including the headline jobs gain of 292,000 in December 2015, headline payroll employment now is about 4.9-million jobs above its pre-recession peak.

Graphs 12 and 13 show the headline payroll series, both on a shorter-term basis, since 2000, and on a longer-term historical basis, from 1945. In perspective, the longer-term graph of the headline payroll-employment levels shows the extreme duration of what had been the official non-recovery in payrolls, the worst such circumstance of the post-Great Depression era.

Beyond excessive upside add-factor biases built into the monthly calculations (see the Birth-Death Model section), the problem remains that payroll employment counts the number of jobs, not the number of people who are employed. Much of that payroll “jobs” growth is in multiple part-time jobs—many taken on for economic reasons—where full-time employment has been desired but could not be found.

Graph 12: Nonfarm Payroll Employment to December 2015

Graph 13: Nonfarm Payroll Employment 1945 to December 2015

Full-Time Employment versus Part-Time Payroll Jobs. Shown in Graph 14, the level of full-time employment (Household Survey) again has recovered its pre-recession high, at least briefly. Headline December 2015 detail—updated for 205 revisions—now stands at 728,000 above the pre-recession high for the series, thanks in particular to the irregularly volatile gain of 504,000 jobs in December 2015. That will gyrate further in the next several months, likely to drop from the current headline level.

Again, such compares with the headline payroll-employment level that now is 4.9-million above its pre-recession high, having regained its peak some 20-months ago. Again, the payroll count is of jobs, not people, where much of that payroll “jobs” growth has been in part-time, and in multiple part-time jobs, many taken on for economic reasons, where full-time employment was desired but could not be found.

As a separate consideration and an indication of the level of nonsensical GDP reporting, where employment traditionally is a coincident indicator of broad economic activity, again the GDP purportedly recovered its pre-recession high some four years ago, more than two years before similar payroll activity, and some four years before the temporary current recovery in full-time employment.

Graphs 15 and 16 plot comparisons of activity in full-time employment versus payroll jobs, post-economic collapse. Full-time employment was hit hardest, with headline employment “recovery” coming largely from individuals having to settle for part-time work.

Headline month-to-month volatility in the full-time employment reporting is more a function of the instabilities from the non-comparability of the headline, seasonally-adjusted monthly data (see the discussion in the Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors section), than it is as an indicator of actual month-to-month volatility in economic activity.

Graph 14: Full-Time Employment (Household Survey) to December2015

Graph 15: Full-Time Employment (Household Survey) versus Jobs Count (Payroll Survey)

Graph 16: Full-Time Employment (Household Survey) versus Jobs Count (Payroll Survey), Year-to-Year

The graph of full-time employment excludes the count of those employed with only part-time jobs, one or more. Total employment, including those employed with part-time work, has recovered its pre-recession high, but it still is not close to the payroll reporting. Again, the Household-Survey numbers count the number of people who have at least one job. The Payroll Survey simply counts the number of jobs (see Commentary No. 686 for further detail).

Annual Percent Change in Headline Payrolls—Slowing Growth. Not-seasonally-adjusted, year-to-year change in payroll employment is untouched by the concurrent-seasonal-adjustment issues, so the monthly comparisons of year-to-year change at least are reported on a consistent basis. Yet, a possible new redefinition of the series—not the standard benchmarking process in 2014—appears to be in play, on top of the prior distortions from the 2013 benchmarking (see Commentary No. 598).

With the 2014 benchmarked surges built into recent headline payroll activity, patterns of year-to-year growth in unadjusted payrolls also moved higher, setting a post-recession high of 2.39% in February 2015. Such was the strongest annual growth since June 2000 (another recession), but subsequent annual growth has slowed. Year-to-year nonfarm payroll growth in December 2015 held at 1.91%, the same level as a revised 1.91% [previously 1.87%] in November 2015, down from a revised annual gain of 1.96% [previously up by 1.97%, initially up by 1.95%] in October 2015, and unrevised gains of 1.92% in September 2015, 2.03% in August 2015, and a 2.18% gain in July 2015. The November and December 2015 readings were tied as the weakest annual growth rates in the last nineteen months.

Graph 17: Payroll Employment, Year-to-Year Percent Change, to December 2015

Graph 18: Payroll Employment, Year-to-Year Percent Change, 1945 to December 2015

With bottom-bouncing patterns of recent years, current headline annual growth has recovered from the post-World War II record decline of 5.02% (-5.02%) seen in August 2009, as shown in the accompanying graphs. That decline remains the most severe annual contraction since the production shutdown at the end of World War II [a trough of a 7.59% (-7.59%) annual contraction in September 1945]. Disallowing the post-war shutdown as a normal business cycle, the August 2009 annual decline was the worst since the Great Depression.

Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent-Seasonal Factors. Detailed in Commentary No. 694 and Commentary No. 695, there are serious and deliberate reporting flaws with the government’s seasonally-adjusted, monthly reporting of both employment and unemployment. Each month, the BLS uses a concurrent-seasonal-adjustment process to adjust both the payroll and unemployment data for the latest seasonal patterns. As new headline data are seasonally-adjusted for each series, the re-adjustment process also revises the monthly history of each series, recalculating prior, adjusted reporting for every month, going back five years, so as to be consistent with the new seasonal patterns that generated the current headline number.

Effective Reporting Fraud. The problem remains that the BLS does not publish the monthly historical revisions along with the new headline data. As a result, current headline reporting is neither consistent nor comparable with prior data, and the unreported actual monthly variations versus headline detail can be large. The deliberately-misleading reporting effectively is a fraud. The problem is not with the BLS using concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors, it is with the BLS not publishing consistent data, where those data are calculated each month and are available internally to the Bureau.

Household Survey. In the case of the published Household Survey (unemployment rate and related data), the seasonally-adjusted headline numbers usually are not comparable with the prior monthly data or any month before. Accordingly, the published headline detail as to whether the unemployment rate was up, down or unchanged in a given month is not meaningful, and what actually happened is not knowable by the public. Month-to-month comparisons of these popular numbers are of no substance, other than for market hyping or political propaganda.

The headline month-to-month reporting in the Household Survey is made consistent only in the once-per-year reporting of December data, seen with this month’s headline reporting and annual revisions back for five years. All historical comparability evaporates, though, with the ensuing month’s headline January reporting, and with each monthly estimate thereafter.

Payroll or Establishment Survey. In the case of the published Payroll Survey data (payroll-employment change and related detail), monthly changes in the seasonally-adjusted headline December 2015 data are comparable only with the headline changes in the November 2015 numbers, not with October 2015 or any earlier months. Due to the BLS modeling process, the historical data never are published on a consistent basis, even with publication of the annual benchmark revision, as discussed shortly.

No one seems to mind if the published earlier numbers are wrong, particularly if unstable seasonal-adjustment patterns have shifted prior jobs growth or reduced unemployment into current reporting, as often is the case. In the current reporting, October-to-December 2015 payrolls appears to have been warped at least partially with revamped seasonals adjustments, temporarily stealing seasonal growth from the current month, without any formal indication of related shifting detail in the previously-published historical data.

Graph 19: Monthly Concurrent-Seasonal-Factor Irregularities with Monthly Payroll Employment

Graph 20: Monthly Concurrent-Seasonal-Factor Irregularities - Headline November versus December 2015

The BLS does provide modeling detail for the Payroll Survey, allowing for third-party calculations, but no such accommodation has been made for the Household Survey. ShadowStats affiliate www.ExpliStats.com does such third-party calculations for the payroll series, and the resulting detail of the differences between the current headline reporting and the constantly-shifting, consistent and comparable history are plotted in the accompanying graphs.

Graph 19 details how far the monthly payroll employment data have strayed from being consistent with the most recent benchmark revision. The gray line shows the December 2014 pattern versus the 2013-benchmark revision, and the color-coded lines show the January to November 2015 patterns of distortion versus the 2014-benchmark. Due to several months of testing of the model, before the benchmark release, the BLS never publishes the historical data on a consistent basis. Such will be the case with next month’s benchmarking and new graphs.

A comparison of the heavy, dark-blue line (December 2015) with the thinner red line (November 2015), shows shifts in seasonal factors in December 2014 and January 2015 numbers, as well as a continued shift in June 2015 to September 2015. The seasonal shifts in those timeframes indicated unreported and inconsistent seasonal-adjustment pressures in current headline detail. Such is seen more easily in Graph 20, which plots just the isolated detail from November and December 2015.

If the headline monthly reporting were comparable and stable, month-after-month, all the lines in Graphs 19 and 20 would be flat and at zero. Again, with the payroll series, only the headline month and the prior month are consistent in terms of month-to-month reporting detail (headline October 2015 no longer is comparable with data from September 2015 or earlier). Again, comparable with headline December and November reporting, October’s current headline jobs gain of 307,000 was overstated by 15,000 (up by 292,000 on a consistent basis). Monthly discrepancies have been as large as 100,000 jobs.

Birth-Death/Bias-Factor Adjustment. Despite the ongoing, general overstatement of monthly payroll employment, the BLS adds in upside monthly biases to the payroll employment numbers. The continual overstatement is evidenced usually by regular and massive, annual downward benchmark revisions (2011 and 2012 and 2014 excepted). As discussed in the benchmark detail of Commentary No. 598, the regular benchmark revision to March 2013 payroll employment was to the downside by 119,000, where the BLS had overestimated standard payroll employment growth.

With the March 2013 revision, though, the BLS separately redefined the Payroll Survey so as to include 466,000 workers who had been in a category not previously counted in payroll employment. The latter event was little more than a gimmicked, upside fudge-factor, used to mask the effects of the regular downside revisions to employment surveying, and likely is the excuse behind the increase in the annual bias factor, where the new category cannot be surveyed easily or regularly by the BLS. Elements tied to this likely had impact on the unusual issues with the 2014 benchmark revisions.

Abuses from the 2014 benchmarking are detailed in Commentary No. 694 and Commentary No. 695. With the headline benchmark revision for March 2014 showing understated payrolls of 67,000 (-67,000), the BLS upped its annual add-factor bias by an even greater 161,000 for the year ahead, to 892,000.

The BLS has announced a preliminary downside revision of 208,000 (-208,000) jobs to the base March 2015 payroll employment levels (see Commentary No. 753 of September 17th for details). Such had been suggested from earlier shifts in existing bias factors. As has been standard BLS practice, there is no good political reason for risking a headline understatement of jobs growth, so the ultimate, actual benchmarking for 2015, to be published next month, on February 5, 2016, will speak for itself.

Historically, the upside-bias process was created simply by adding in a monthly “bias factor,” so as to prevent the otherwise potential political embarrassment to the BLS of understating monthly jobs growth. The “bias factor” process resulted from such an actual embarrassment, with the underestimation of jobs growth coming out of the 1983 recession. That process eventually was recast as the now infamous Birth-Death Model (BDM), which purportedly models the relative effects on payroll employment of jobs creation due to new businesses starting up, versus jobs lost due to bankruptcies or closings of existing businesses.

December 2015 Add-Factor Bias. The not-seasonally-adjusted December 2015 bias was a negative monthly add-factor of 23,000 (-23,000), versus a positive add-factor 15,000 in November 2015, and a negative add-factor of 15,000 (-15,000) in December 2014.

The revamped, aggregate upside bias for the trailing twelve months through December 2015 was 781,000, versus 789,000 in November, 790,000 in October, 789,000 in September, 804,000 in August, 797,000 in July, 836,000 in June and 856,000 in May, but still higher than the pre-2014-benchmarked level of 731,000 in December 2014. That is a rough-monthly average of 65,000 in December (versus 61,000 pre-2014 benchmark) jobs created out of thin air, on top of some indeterminable amount of other jobs that are lost in the economy from business closings. Those losses simply are assumed away by the BLS in the BDM, as discussed below.

Problems with the Model. The aggregated upside annual reporting bias in the BDM reflects an ongoing assumption of a net positive jobs creation by new companies versus those going out of business. Such becomes a self-fulfilling system, as the upside biases boost reporting for financial-market and political needs, with relatively good headline data, while often also setting up downside benchmark revisions for the next year, which traditionally are ignored by the media and the politicians. The BLS cannot measure meaningfully the impact of jobs loss and jobs creation from employers starting up or going out of business, on a timely basis (within at least five years, if ever), or by changes in household employment that were incorporated into the 2014 redefined payroll series. Such information simply is guesstimated by the BLS, along with the addition of a bias-factor generated by the BDM.

Positive assumptions—commonly built into government statistical reporting and modeling—tend to result in overstated official estimates of general economic growth. Along with these happy guesstimates, there usually are underlying assumptions of perpetual economic growth in most models. Accordingly, the functioning and relevance of those models become impaired during periods of economic downturn, and the current, ongoing downturn has been the most severe—in depth as well as duration—since the Great Depression.

Indeed, historically, the BDM biases have tended to overstate payroll employment levels—to understate employment declines—during recessions. There is a faulty underlying premise here that jobs created by start-up companies in this downturn have more than offset jobs lost by companies going out of business. Recent studies have suggested that there is a net jobs loss, not gain, in this circumstance. So, if a company fails to report its payrolls because it has gone out of business (or has been devastated by a hurricane), the BLS assumes the firm still has its previously-reported employees and adjusts those numbers for the trend in the company’s industry.

Further, the presumed net additional “surplus” jobs created by start-up firms are added on to the payroll estimates each month as a special add-factor. These add-factors are set now to add an average of 65,000 jobs per month in the current year. In current reporting, the aggregate average overstatement of employment change easily exceeds 200,000 jobs per month.

HOUSEHOLD SURVEY DETAIL. The December 2015 annual Household–Survey revisions are reflected in all related numerical and graphic detail in this Commentary. Discussed in the Opening Comments, the annual revisions were unusually minimal. To the extent that the month-to-month, seasonally-adjusted Household-Series details are comparable in today’s Commentary, that is for one month only. All the regular comparability and consistency issues resume with next month’s headline January 2016 reporting, complicated by once-per-year adjustments to the headline population estimates.

Separately, detailed in Commentary No. 669, significant issues as to falsification of the data gathered in the monthly Current Population Survey (CPS), conducted by the Census Bureau, have been raised in the press and investigated by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform and the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. Further investigation purportedly is underway in Congress. CPS is the source of the Household Survey used by the BLS in estimating monthly unemployment, employment, etc. Accordingly, the statistical significance of the headline reporting detail here is open to serious question.

Headline Unemployment Rates. At the first decimal point, the headline December 2015 unemployment rate (U.3) was unchanged, holding 5.0% for the third month. At the second decimal point, headline December U.3 declined by 0.03-percentage point to 5.01% from a revised 5.04% [previously 5.05%, which was a rounded headline 5.0%]. Technically, the headline December decline in U.3 was statistically-insignificant, where the official 95% confidence interval around a monthly change in headline U.3 is +/- 0.23-percentage point.

The headline gain change in U.3 also usually is without meaning, given that the seasonally-adjusted, month-to-month details simply are not comparable, thanks to the BLS’s reporting methodology and use of concurrent-seasonal-adjustment factors (see Headline Distortions from Shifting Concurrent Seasonal Factors in the Reporting Detail). Yet, the revised December 2015 Household-Survey detail have been restated for a consistent, seasonally-adjusted history back for five years. This once-per-year revision will revert to month-to-month non-comparability of the seasonally-adjusted numbers with subsequent January 2016 reporting. These issues remain separate from official questions raised as to falsification of the Current Population Survey (CPS), from which are derived the unemployment details.

On an unadjusted basis, the unemployment rates are not revised and always are consistent in post-1994 reporting methodology. The December 2015 unadjusted U.3 unemployment rate eased to 4.80% versus 4.81% in November.

The minimal decline in the seasonally-adjusted, headline December 2015 U.3 unemployment rate reflected a decline of 20,000 (-20,000) unemployed individuals with a gain of 485,000 employed, and an aggregate gain of 466,000 in the labor force. The changes here are suggestive of poor-quality seasonal adjustments tied to the holiday season, which should tend to reverse in subsequent reporting.

New discouraged and otherwise marginally-attached workers always are moving into U.6 unemployment accounting from U.3, while those who have been discouraged for one year continuously are dropped from the U.6 measure. As a result, the U.6 measure has been easing along with U.3, for a while, but those being pushed out of U.6 still are counted in the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate, which has remained stable.

U.6 Unemployment Rate. The broadest unemployment rate published by the BLS, U.6 includes accounting for those marginally attached to the labor force (including short-term discouraged workers) and those who are employed part-time for economic reasons (i.e., they cannot find a full-time job).

With a negligible decline in the underlying seasonally-adjusted U.3 rate, a small decline in the adjusted number of people working part-time for economic reasons, and a more-than -offsetting gain in those marginally attached to the workforce (short-term discouraged workers rose for the month), headline December 2015 U.6 unemployment softened negligibly to 9.87%. That was against a revised 9.89% [previously 9.90%] in November. The unadjusted U.6 unemployment rate was at 9.78% in December 2015, versus 9.59% in November.

“Short-Term” Discouraged Workers. The count of short-term discouraged workers in December 2015 (never seasonally-adjusted) rose by 69,000 to 663,000, from 594,000 in November 2015, where the total, short-term marginally-attached discouraged workers rose to 1,833,000 in December 2015, from 1,717,000 in November 2015. The latest, official discouraged number reflected the flow of the headline unemployed—giving up looking for work—leaving the headline U.3 unemployment category and being rolled into the U.6 measure as short-term “marginally-attached discouraged workers,” net of the further increase in the number of those moving from short-term discouraged-worker status into the netherworld of long-term discouraged-worker status.

It is the long-term discouraged-worker category that defines the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Measure. There is a continuing rollover from the short-term to the long-term category, with the ShadowStats measure encompassing U.6 and the short-term discouraged workers, plus the long-term discouraged workers. In 1994, “discouraged workers”—those who had given up looking for a job because there were no jobs to be had—were redefined so as to be counted only if they had been “discouraged” for less than a year. This time qualification defined away a large number of long-term discouraged workers. The remaining redefined short-term discouraged and redefined marginally-attached workers were included in U.6.

ShadowStats Alternate Unemployment Estimate. Adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of the still-growing ranks of excluded, long-term discouraged workers—a broad unemployment measure more in line with common experience—the ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate held at 22.9% in December 2015, the same as in November.

Off the October 2015 near-term low of 22.8%, the ShadowStats December 2015 reading still was down by 40 basis points or by 0.4% (-0.4%) from the 23.3% series high in December 2013. In contrast, the headline U.3 reading for December 2015 of 5.0% was tied with the October and November 2015 readings as the lowest rate since February of 2008, down from its 10.0% peak in April 2010 by a full 500 (-500) basis points or 5.0% (-5.0%).

Again, the ShadowStats estimate generally shows the toll of long-term unemployed leaving the headline labor force, as discussed in greater detail in the following section.

SHADOWSTATS-ALTERNATE UNEMPLOYMENT RATE MEASURE. In 1994, the BLS overhauled its system for estimating unemployment, including changing survey questions and unemployment definitions. In the new system, measurement of the previously-defined discouraged workers disappeared. These were individuals who had given up looking for work, because there was no work to be had. These people, who considered themselves unemployed, had been counted in the old survey, irrespective of how long they had not been looking for work.

The new survey questions and definitions had the effect of minimizing the impact on unemployment reporting for those workers about to be displaced by the just-implemented North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). At the time, I had close ties with an old-line consumer polling company, whose substantial economic monthly surveys were compared closely with census-survey details. The new surveying changed the numbers, and what had been the discouraged-worker category soon became undercounted or effectively eliminated. Change or reword a survey question, and change definitions, you can affect the survey results meaningfully.

The post-1994 survey techniques also fell far shy of adequately measuring the long-term displacement of workers tied to the economic collapse into 2008 and 2009, and from the lack of subsequent economic recovery. The BLS has a category for those not in the labor force who currently want a job. Net of the currently-defined “marginally attached workers,” which includes the currently-defined “discouraged workers” category used in the U.6, those not in the labor force currently wanting a job rose to 3.872 million in December 2015 versus 3.608 million in November 2015. While some will contend that that number includes all those otherwise-uncounted discouraged workers, such is far shy of underlying reality.

The ShadowStats number—a broad unemployment measure more in line with common experience—is my estimate. The approximation of the ShadowStats “long-term discouraged worker” category—those otherwise largely defined out of statistical existence in 1994—reflects proprietary modeling based on a variety of private and public surveying over the last two decades. Beyond using the BLS U.6 estimate as an underlying monthly base, I have not found a way of accounting fully for the current unemployment circumstance and common experience using just the monthly headline data from the BLS.

Some broad systemic labor measures from the BLS, though, are consistent in pattern with the ShadowStats measure, even allowing for shifts tied to an aging population. Shown in the Opening Comments, the graph of the inverted ShadowStats unemployment measure has a strong correlation with the employment-to-population ratio, in conjunction with the labor-force participation rate, as well as with the ShadowStats-Alternate GDP Estimate and S&P 500 Real Revenues (see No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary). The labor-related series all are plotted subsequent to the 1994 overhaul of unemployment surveying (see Graph 2 to 6).

Headline December 2015 Detail. Again, adding back into the total unemployed and labor force the ShadowStats estimate of long-term discouraged workers, the December 2015 ShadowStats-Alternate Unemployment Estimate held even with November at 22.9%. The December reading was down by 40 basis points or 0.40% (-0.40%) from the 23.3% series high in December 2013. In line with minimal annual revisions to the seasonally-adjusted headline Household Survey detail, the ShadowStats measure revised higher by 0.1% in September 2013 and September 2014, and down by 0.1% in May 2015.

Again, in contrast, the December 2015 headline U.3 unemployment reading of 5.0% continued to hold at the lowest level since February 2008, down by a full 500 basis points or 5.00% (-5.00%) from its peak of 10.0% in April 2010.

As seen in the usual graph of the various unemployment measures (Graph 1 in the Opening Comments), there continues to be a noticeable divergence in the ShadowStats series versus U.6 and U.3, with the headline BLS headline unemployment measures heading lower against a currently-stagnant, high-level ShadowStats number.

The reason for this is that U.6, again, only includes discouraged and marginally-attached workers who have been discouraged for less than a year. As the discouraged-worker status ages, those that go beyond one year fall off the government counting, even as new workers enter “discouraged” status. A similar pattern of U.3 unemployed becoming “discouraged” or otherwise marginally attached, and moving into the U.6 category also accounts for the early divergence between the U.6 and U.3 categories.

With the continual rollover, the flow of headline workers continues into the short-term discouraged workers category (U.6), and from U.6 into long-term discouraged worker status (the ShadowStats measure). There was a lag in this happening as those having difficulty during the early months of the economic collapse, first moved into short-term discouraged status, and then, a year later they began moving increasingly into long-term discouraged status, hence the lack of earlier divergence between the series. The movement of the discouraged unemployed out of the headline labor force had been accelerating. While there is attrition in long-term discouraged numbers, there is no set cut off where the long-term discouraged workers cease to exist. See the Alternate Data tab for historical detail.

Generally, where the U.6 largely encompasses U.3, the ShadowStats measure encompasses U.6. To the extent that a decline in U.3 reflects unemployed moving into U.6, or a decline in U.6 reflects short-term discouraged workers moving into the ShadowStats number, the ShadowStats number continues to encompass all the unemployed, irrespective of the series from which they otherwise may have been ejected.

Great Depression Comparisons. As discussed in these regular Commentaries covering the monthly unemployment circumstance, an unemployment rate around 23% might raise questions in terms of a comparison with the purported peak unemployment in the Great Depression (1933) of 25%. Hard estimates of the ShadowStats series are difficult to generate on a regular monthly basis before 1994, given meaningful reporting inconsistencies created by the BLS when it revamped unemployment reporting at that time. Nonetheless, as best estimated, the current ShadowStats level likely is about as bad as the peak actual unemployment seen in the 1973-to-1975 recession and in the double-dip recession of the early-1980s.

The Great Depression peak unemployment rate of 25% in 1933 was estimated well after the fact, with 27% of those employed then working on farms. Today, less than 2% of the employed work on farms. Accordingly, a better measure for comparison with the ShadowStats number might be the Great Depression peak in the nonfarm unemployment rate in 1933 of roughly 34% to 35%.

__________

WEEK AHEAD

Economic Reporting Should Trend Much Weaker than Expected, Well into 2016; Inflation Should Rise Anew—Along with Oil Prices—in Response to a Weakening Dollar. Still in a fluctuating, general trend to the downside, amidst increasingly-negative reporting in headline detail, market expectations for business activity nonetheless gyrate with the latest economic hype in the popular media. That effect holds the consensus outlook at overly-optimistic, but softening levels, with current expectations still exceeding underlying economic reality. Along with the broad trend in weakening expectations, movement towards looming recession recognition continues at an accelerating pace, as discussed in the Opening Comments of Commentary No. 778, and in December 30th’s No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary.

Headline reporting of the regular monthly economic numbers increasingly should weaken in the weeks and months ahead, along with much worse-than-expected reporting for at least the next several quarters of GDP (and GDI and GNP), for fourth-quarter 2015 and well into 2016. That includes intensifying signals of a headline fourth-quarter 2015 GDP contraction, due for release on January 29, 2016, as well as downside revisions to recent GDP history in the 2016 annual benchmark revision due on July 29, 2016.

CPI-U consumer inflation—intermittently driven lower this year by collapsing prices for gasoline and other oil-price related commodities—likely has seen its near-term, year-to-year low. Annual CPI-U turned minimally positive in June 2015, for the first time in six months, notched somewhat higher in July and August, with a minimal fallback in September, tied to renewed weakness in gasoline prices. With positive seasonal adjustments countering some of the monthly weakness in gasoline prices, combined with particularly weak headline inflation one year ago, headline November 2015 CPI-U annual inflation was boosted to 0.5%, with further upside movement in headline annual inflation likely for December reporting. Separately, fundamental reporting issues withe CPI are discussed here: Public Commentary on Inflation Measurement.

Significant inflation pressures should mount anew, at such time as oil prices rebound. Again, that process should accelerate, along with a pending sharp downturn in the exchange-rate value of the U.S. dollar. Those areas, the general economic outlook and longer range reporting trends were reviewed broadly, most recently, in No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary in complement to No. 742 Special Commentary: A World Increasingly Out of Balance, No. 692 Special Commentary: 2015 - A World Out of Balance and the 2014 Hyperinflation Reports: The End Game Begins and Great Economic Tumble.

Note on Reporting-Quality Issues and Systemic-Reporting Biases. Significant reporting-quality problems remain with most major economic series. Beyond the pre-announced gimmicked changes to reporting methodologies of the last several decades, which have tended to understate actual inflation and to overstate actual economic activity, ongoing headline reporting issues are tied largely to systemic distortions of monthly seasonal adjustments. Data instabilities—induced partially by the still-evolving economic turmoil of the last eight-to-ten years—have been without precedent in the post-World War II era of modern-economic reporting. The severity and ongoing nature of the downturn provide particularly unstable headline economic results, when concurrent seasonal adjustments are used (as with retail sales, durable goods orders, employment and unemployment data, discussed and explored in the labor-numbers related Commentary No. 695).

Separately, discussed in Commentary No. 778, a heretofore unheard of spate of “processing errors” has surfaced, currently involving surveys of earnings and construction spending. This is suggestive of deteriorating internal oversight and control of the U.S. government’s headline economic reporting. At the same time, it indicates an openness of the involved statistical agencies in revealing the reporting-quality issues. Combined with recent allegations of Census Bureau falsification of data in its monthly Current Population Survey (the source for the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Household Survey), these issues have thrown into question the statistical-significance of the headline month-to-month reporting for many popular economic series (see Commentary No. 669).

PENDING RELEASES:

Nominal and Real Retail Sales (December 2015). The Census Bureau has scheduled release of December 2015 nominal (not-adjusted-for-inflation) Retail Sales for Friday, January 15th, which will be covered in Commentary No. 780 of that date. Real (inflation-adjusted) Retail Sales for December will follow in ShadowStats Commentary No. 781 of January 20th, in conjunction with the publication of detail on headline December CPI-U. With a fair chance for a flat-to-minimally-positive headline monthly gain in December CPI inflation, there is a parallel chance for real growth in December sales to be minimally weaker than the headline nominal sales activity. The pace of annual CPI-U inflation, however, should increase sharply once again, intensifying the recession signal currently generated by annual real growth in retail sales.

Market expectations likely will be on the plus-side of flat for the nominal numbers, again. In the current environment, however, downside-reporting surprises remain a good bet for this series, including a much weaker-than-expected headline number for the largest retail-shopping month of the year, along with potential downside revisions to the October and November detail. An outright contraction in headline December activity is a good possibility. Continued weakness in these numbers should intensify the shift in consensus expectations towards a fourth-quarter GDP decline, a renewed economic contraction or “new” recession.

Constraining retail sales activity, the consumer remains in an extreme liquidity bind with weakening confidence, discussed broadly in No. 777 Year-End Special Commentary. Without sustained growth in real income, and without the ability and/or willingness to take on meaningful new debt in order to make up for the income shortfall, the U.S. consumer is unable to sustain positive growth in domestic personal consumption, including retail sales, real or otherwise.